A fascinating love story plays out during the end-days of the DDR.

Sheena Kalayil | The Others | Fly on the Wall Press: £12.99

Reviewed by Joseph Hunter

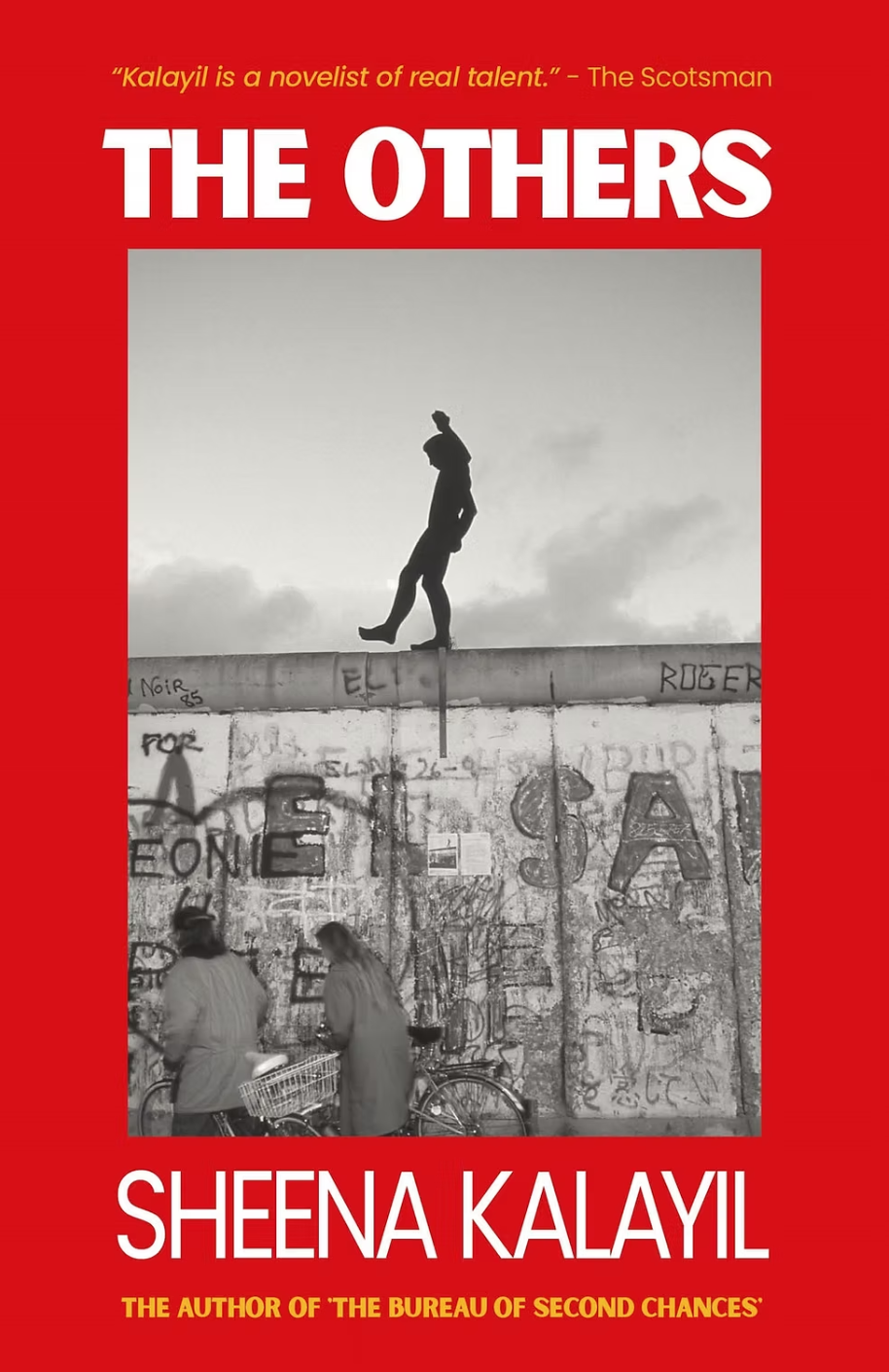

The inciting incident in The Others, Sheena Kalayil’s stirring and sad fourth novel, involves the discovery of a body. A young German man has drowned in an attempt to escape the Deutsche Demokratische Republik (DDR) by paddling across to Denmark on a surfboard. The man’s name, cause of death, and motives are all speculated about afterwards by the two people who find him – bodies, in this novel, have tales to tell.

Escape attempts such as this are routinely hushed up by the authorities, a fact that Lolita and Armando – the two people who find the body – are well aware of. Further complicating matters is that both of them are, in different ways, outsiders in the DDR. Lolita is a trainee doctor originally from India, while Armando is from Mozambique, working in a German factory as part of a work exchange agreement between the DDR and his African homeland. Being connected to the body and the escape attempt is therefore extra-problematic for them both, and risks jeopardising their already-somewhat-tenuous status. There is also the matter of Armando’s daughter, Clara, the product of a short affair with a German woman, Petra. Leaving the DDR – or being forced out – might mean leaving her life for good.

Into this fascinating, intersectional landscape Kalayil introduces a nuanced love story that is by turns passionate and melancholic. Armando and Lolita are deeply attracted to one another, but their burgeoning romance is stymied by circumstance. Although she adores the little girl, Lolita is jealous of Armando’s existing obligations to Clara and Petra. Armando is cowed by his uncertain status, reflecting at one point on Petra’s critique of his ‘internalised colonisation’. And all the while there is fear of the Stasi, who may be watching, connecting them with the dead boy’s escape attempt.

Initially, Armando and Lolita’s developing entanglement is explored in chapters that alternate between their perspectives, narrated in close third person with internal focalisation. Their feelings about each other, and about the citizens of their troubled adopted country, are delivered with searching interiority and natural dialogue. Lolita and Armando’s status as ‘other’ gives them unique insight into life in the DDR, and their place within it:

‘Do many people try to get across to Denmark?’

‘I don’t know. But I think some do, yes.’

‘Why?’

He smiles ruefully, his eyes crinkling at the edges.

‘For you and me this might be paradise, Lolita. For them no.’

‘Do you think this is paradise, Armando?’

‘I know that if I had not come here, I might be dead.’ (30)

In the second of the novel’s five parts, a third key character and perspective is offered. The arrival into Lolita’s life of a young aspiring writer, Berlin-born Theo, establishes a love-triangle. Theo is captivated by Lolita, pursuing her, and there are at times suggestions of exoticisation in his enamoured gaze:

She is waiting outside the residence, wearing jeans and a soft sleeveless top that he would describe as Indian in nature, from its cut and embroidery. Her long hair is arranged in a style his sister would describe as half up and half down, and she wears long, dangly earrings and jangly bangles. He reminds himself that she has not dressed solely for his benefit… (103-4)

Indeed, as their friendship deepens, Theo literally finds new shades in Lolita: ‘She looks up at him. While her eyes are a deep shade of brown, each has a light orange trim around the pupil.’ (107) Selected for Stasi training as a teenager, Theo refused to join on moral grounds, a stance that denied him a university education – the same attention to detail that would have made him an effective secret policeman is put to use in a different way as a writer. He and Armando become rivals for Lolita’s love, but it is a rivalry imbued with mutual respect, even admiration:

[Theo] knows his rival now, for that is indeed what Armando is. And quite a rival: taller and stronger, like a dark-skinned Greek god. Handsome, with wide set eyes and cut-glass cheekbones. Against such a man, he himself appears a boy. (119)

But this love triangle has sharp edges. In the DDR, for these people, every personal desire is tempered and complicated by social and historical factors. These are characters who are aware of the uncertainty of the times they live in – that they are experiencing history being written all around them, and all the while battling for their own personal happiness and dignity. They are capable of wounding one another deeply, as when in an unexpected twist it becomes apparent that Theo has inadvertently brought Armando to the attention of the Stasi. As Kalayil unfolds this deft narrative it becomes apparent to the reader that, in this context, no romance can have a neat or happy ending.

As the title suggests, The Others draws attention to those who have been othered by history. But it shows, too, that none of us are easily defined as this thing or that. East, West, black, white, free, unfree – all are messy and imperfect distinctions. Each person is a blend, a multitude: place, circumstance, and luck. Who we happen to meet and who we happen to love – time and chance happens to us all. Kalayil understands that – to modify a phrase – the personal is the historical. This novel demonstrates that the two are, always, intertwined. Sometimes overlapping, sometimes at odds. A wonderful set-piece narrates Theo and Lolita in Berlin on the night that the Wall falls. Caught up in the crowd, they seem literally swept along by history. However, the unexpected appearance of Armando turns a moment of national celebration into personal heartache for Theo, as Lolita and Armando leave him and walk away from the falling Wall, back East, alone together. Armando reflects:

…he can think of no better way to savour Lolita’s company than to travel in the opposite direction, away from the story that will be told and re-told over the years to come. (226)

This novel tells the story of people pushed to the margins, othered, but who are shown with their dreams, beauty, and integrity intact. People who are attempting to carve out space for themselves in a changing, sometimes hostile world. Many of the elements at work during the collapse of the DDR – the uncertain status of immigrants, political and social instability, an under-threat welfare state – seem again to be of great relevance to us, today. But the truly human import of such weighty themes is, in this novel, enacted through things that are evergreen. Love, requited and unrequited, romantic and familial. Duty and obligation. Friendship. Hope. Loss. The things that bind, and the things that sunder.

Reviewed by Joseph Hunter