A quietly striking collection where readers are left to meditate upon the enigmatic traces of Fernández’s words, and where they might point.

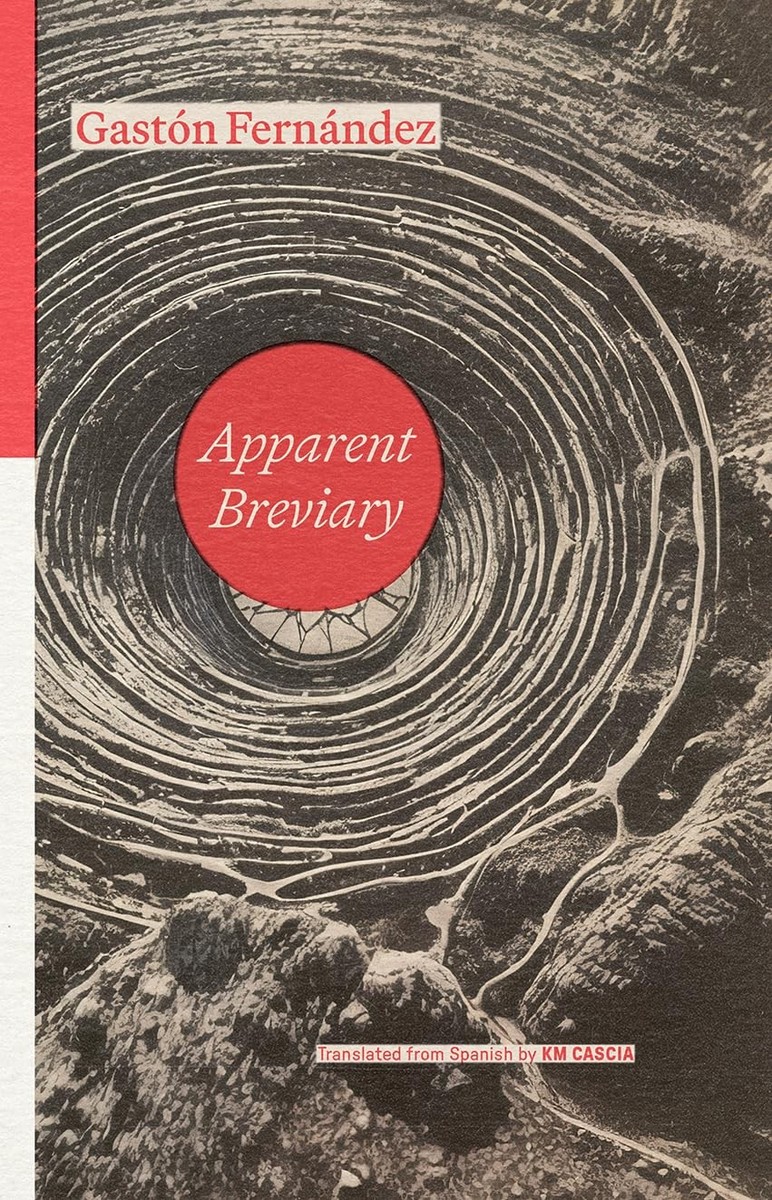

Gastón Fernández | Apparent Breviary (trans. KM Cascia) | World Poetry Books £19.99

Reviewed by Astrid Meyer

Apparent Breviary, written between 1980-1981 by the Peruvian poet Gastón Fernández, translated from the Spanish into English in 2025 by KM Cascia, deals largely in traces and ephemerality. ‘Breviary’, which comes from the Latin breviarium, meaning ‘abridgement’, and brevis, ‘short, brief’, denotes an abridged version of the Psalms, an apt title for a work filled with Biblical allusion and echoes. Fernández is sometimes tentatively dubbed a neo-baroque writer, in KM Cascia’s words, because (quoting a leading figure of the neo-baroque movement, Severo Sarduy) ‘his poetry is made almost entirely out of “the absent signified”’ (page ix). This collection, which consists of 100 single-page poems, offers an attempt to circumscribe in language that which is ungraspable, and perhaps ultimately unknowable. The poems seem almost to float in the ample white space in which they are inset, which also forms an integral part of their structure. In fact, it is as though the poems arise out of a silence, formally signified by the visual space and gaps that also frequently function as punctuation to signal pauses – spaces in which readers might draw breath. Thus, employing Jason Allen-Paisant’s ideas, the silence constitutes a material ‘presence’, inviting readers to confront that which language cannot fully hold.

The poems are sparse, lucid, and dreamlike, each a discrete piece within a larger, patterned whole – like a breviary – as words and phrases repeat themselves throughout, often with slight variation. Unsettling undertones of violence also run through the collection, urging readers to take note. For instance, ‘Without a trace: all that antiquity of air / ubiquitous / as a blowgun / in the image of an eye’ (poem 67), and later, ‘Precipitation without militias the body / knows not the flow of the area on surface / […] Blood / Lord / for the backward of bullets’ (81). Further, state-sanctioned violence, for which ‘medal’ perhaps stands as a metonym, is also subject to contemptuous ridicule, deemed ‘vanity’:

Derision on the brow

on the medal

in the blood

Lord,

if in the eye’s measure

air confronts the certainties

of vanity (17)

Moreover, a relationship between text and body is established: the two are frequently positioned as interchangeable. In fact, the text itself becomes a kind of fragmented, perhaps dismembered ‘body’: ‘derision / centers in the mouth / between pores of / letters’ (15). Elsewhere, Fernández writes, ‘Plausible / sonority, same / as blood’ (31), thereby equating ‘sonority’, e.g. that of a poem’s, with ‘blood’.

Fernández’s text also frequently offers a meta-poetic commentary on the practice of writing, focussing on how language is constructed, and on the materiality of poetry, underscored by the frequent references to ‘book’ throughout. ‘Rage is a noun’, the speaker notes, ‘Either know a poet in a book Or put / one’s conscience on / a cloud’ (14). In the final stanza, the poem, which concerns senseless violence, descends almost into the nonsensical, thereby expressing the horror of conflict that cannot necessarily be comprehended or showcased through language alone. This is perhaps a nod to Peru’s politically fraught recent history involving periods of military rule, rampant corruption, and restricted civil rights. The poem ends disquietingly: ‘death to the phoneme so there will be no / death and / murder man / no reason / no prose / no poem’ (14), the breakdown of the syntax formally enacting the ‘no reason’ of violence – the insensibility of the cited ‘murder’. This recalls Hélène Cixous’s assertation in her essay, ‘Coming to Writing’, published in 1992, that ‘we always live without reason; and living is just that, it’s living without-reason, for nothing, at the mercy of time’ (5). Cixous’ ‘nonreason’ of living corresponds to Fernández’s ‘no reason’ of state violence, and perhaps also of the dislocation of exile, as Fernández lived in exile in Belgium from 1969 onwards. Cixous further notes that ‘all my lives are divided between two principal lives […] [d]own below I claw, I am lacerated, I sob […] carnage, limbs, quarterings, tortured bodies, noises, engines, harrow. Up above, face, mouth, aura; torrent of the silence of the heart’ (17). Her language which pits ‘face, mouth, aura’ against bodily suffering and degradation finds its echo in Fernández’s collection which frequently references and isolates individual body parts: ‘Desire is no book / is no word the book closes / mouth / lips, fist / opens’ (54), and, ‘I know the true peal is / on the lips’ (5). Fernández also mentions ‘aura’ on several occasions, for instance,

The body alone now frequently makes fire

word

creates void

on the lip

praises,

reverts to lip

with no aura

with no air

with no poem (69)

The poem seems to chart the word – and the body’s – transfiguration. As Cascia further argues:

[y]ou wonder if the poems may, in fact, actually be the white space, with the words there just to shape it. To draw attention to that “absent signified” mentioned above. Which is the (apparent?) absence of God, an absence gestured at in the overtly religious language, yes, but also in the rest of the vocabulary, in the echo of the Psalms contained in the form. And in the titular concept, a breviary. (x)

This collection calls to mind George Herbert’s sonnet, ‘Prayer (I)’, published in 1633, which frames prayer as bridging the divide between heaven and earth. Prayer is metaphorised by Herbert as ‘The Christian plummet sounding heav’n and earth’, and as a [siege] ‘engine against th’ Almighty’. He thereby surprisingly juxtaposes violent, aggressive diction with the elevated, overtly religious; following the volta, Herbert writes, ‘Exalted manna, gladness of the best, / Heaven in ordinary, man well drest’, thus infusing the ‘ordinary’ with religiosity. In Fernández, however, such exalted religiosity remains ambiguous – its validity is called radically into question, with no final or definite resolve. The ‘apparent’ absence of God towards which the collection gestures thus plays on both senses of the titular word ‘apparent’: obvious or evident, or rather, only seemingly true or real but not necessarily so. A reader is therefore left to meditate upon the enigmatic – and inconclusive – traces of Fernández’s words and where they might point. As Cixous aptly notes: ‘[w]riting [is] a way of leaving no space for death, of pushing back forgetfulness, of never letting oneself be surprised by the abyss. […] To confront perpetually the mystery of the there-not-there. The visible and the invisible’ (3).

Reviewed by Astrid Meyer