• A city of skyscrapers and aircars in a future Malawi

• An Africa ruined by war and climate change

• Human kind split into different species, living on Mars and Venus

‘Sahara’ (2016) by Shadreck Chikoti (Malawi)

‘Land of Light’ (2015) by Stephen Embleton (South Africa)

‘Women are from Venus’ (2015) by Tiseke Chilima (Malawi)

‘One Wit’ This Place’ (2015) by Muthi Nhlema (Malawi)

Her Broken Shadow (2016) excerpt from shooting script, written and directed by Dilman Dila (Uganda)

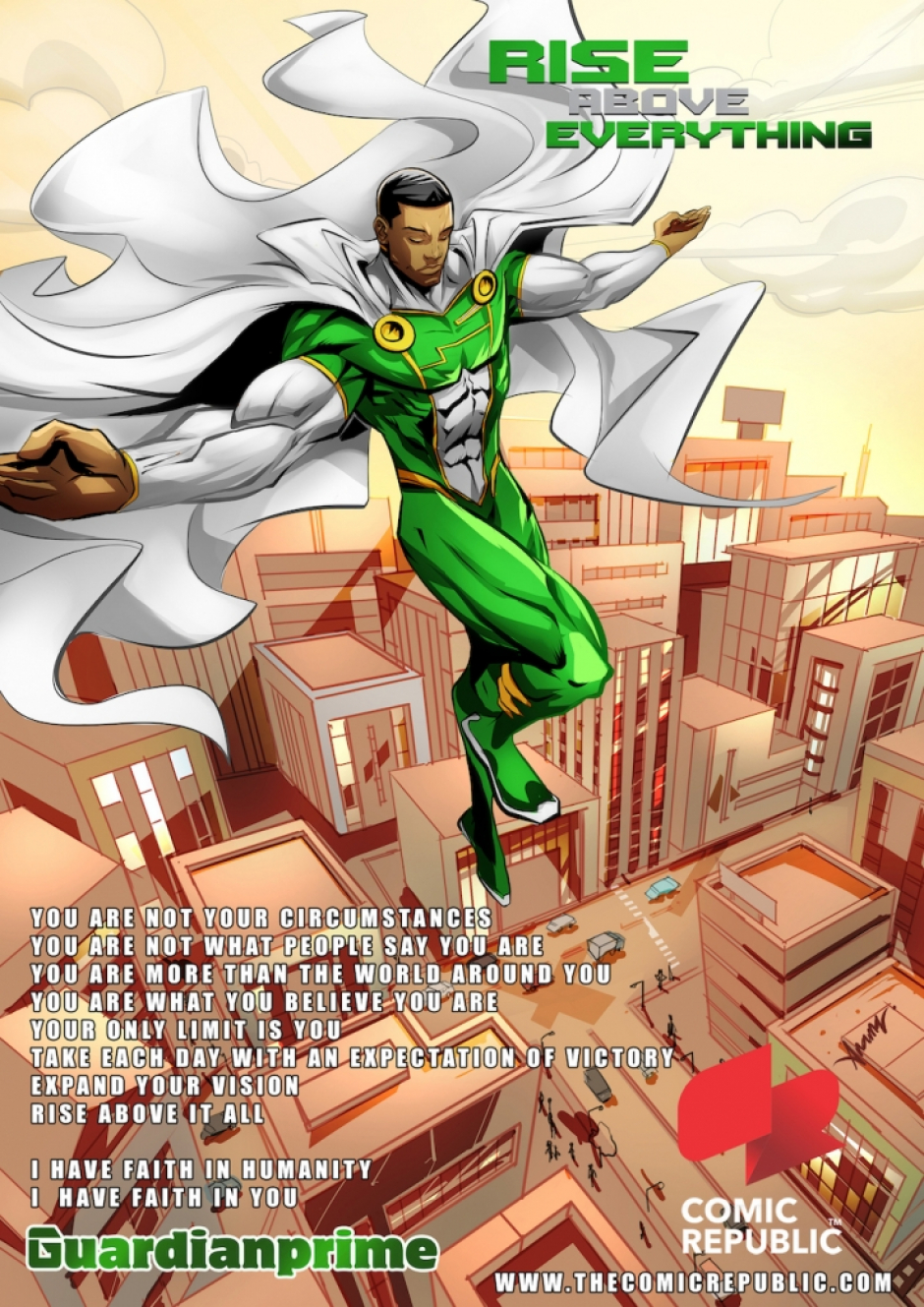

So here it is. This is what so many people say African science fiction is about – envisaging a future for Africa.

And then most of the speculative fiction available seems to be about the past or traditional gods and monsters.

Imagining a future for African is difficult because there are not hundreds of previous stories clearing the ground for you. Every African science fiction story, in order tell a 5000-word tale, has to invent a world from scratch in a way that is not the case for an SFF story set in America, with a long exchange of extrapolative ideas behind it.

Here are dreams of hope and misgiving.

‘Sahara’ by Shadreck Chikoti draws on some of the same material as his restrained novel Azotus the Kingdom, nominated for the Nommo Ilube Award. But it also offers the standard dream of future Africa – skyscrapers and air cars and people who aren’t human.

The next three stories are drawn from Shadreck’s brainchild – Imagine Africa 500, a workshop and anthology that was then edited by Billy Kahora, chief editor at Kwani. At the risk of gutting the anthology we include three stories from it – with Shadreck’s blessing.

One of things colonialism does is disrupt how local cultures deal with death – its rites and observances, but also how the living relate to those who have died. Stephen Embleton’s ‘Land of Light’ offers a vision of harnessing the hydroelectric might of the Congo River…and about new ways of mourning.

‘Woman are from Venus’ may sound like it was inspired by the bestseller on gender relations but as Tiseke Chilima explains in an interview the gender aspect evolved after the Africa 500 workshops. The story opens with a lovely sense of what it would be to have wings and feathers and exemplifies the feminism so common among young Africans. Chilima stands in here for a generation of new self-actuating women writers being published online, such as Innocent Immaculate Acan, Ekari Mbvundula and Lilian Aujo.

‘One Wit This Place’ by Muthi Nhlema is a brief, humane glimpse of a far future in which the planet is lost. For this Malawian writer, West African pidgin stands in for whatever vernacular future language these people speak. Muthi Nhlema is the author of Ta O Reva, nominated for the Nommo Award for Best novella, linked to from the page 21 Tomorrow.

Finally set in the near future, a very far-future indeed and Now, we include an excerpt of the shooting script for Her Broken Shadow written and directed by Dilman Dila. Like some other East African SFF films – including those by Jim Chuchu and Abstract Omega – Her Broken Shadow is artistically ambitious. Two women from different eras are writing a novel about each other. Dilman’s ingenious film finds a good SFF-plot reason for this metafiction. You can view a trailer for the film here.

One thing certainly lies in the future for African SFF writing – publication in Western magazines and journals. Countervailing that – a new interest in publishing fiction in home or local languages. The next section examples those different futures.