The Last Pantheon (2015) by Nick Wood and Tade Thompson (Nigeria, South Africa, UK) parts 1, 2, and 3.

Khamzila’s Adventure – graphic novel (2016) by Ziphosakhe Hlobo and Lena Posch, art by Ethnique Nicole Leonards, with afterword by Monde Sitole (South Africa)

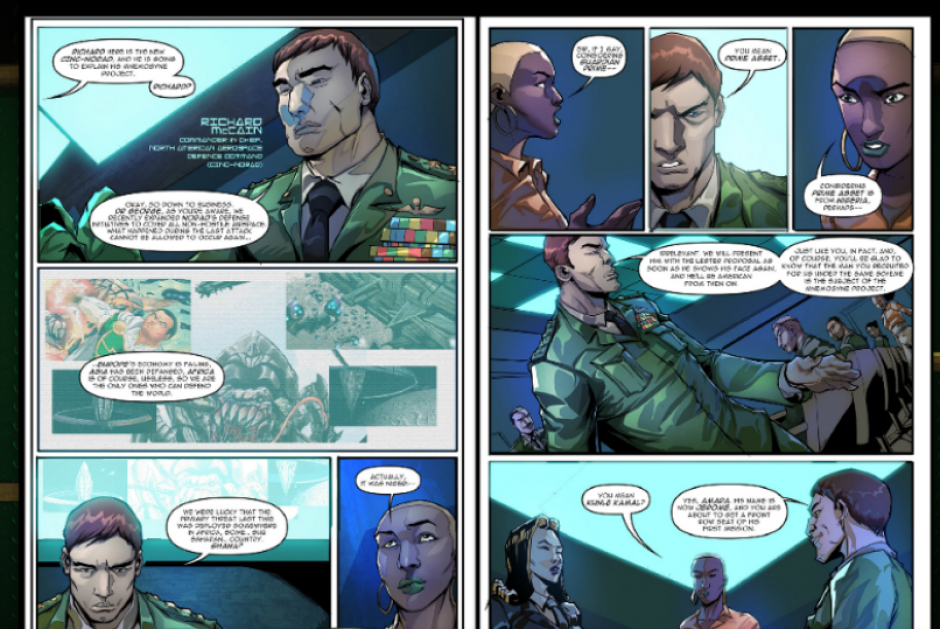

Wale Awelenje was showing me a sequence from the comic Might of Guardian Prime, from Comic Republic, one of at least three innovative comics publishers based in Lagos, Nigeria.

In the sequence the Americans have appropriated ancient African science and weaponized it. The American commander in charge – uniformed, aggressive and obviously intelligent – expounds the situation. But he clearly knows very little about Africa because he cares not to. A female African colleague, with a long-suffering look, corrects him. He’s got a country wrong again.

I realized as Wale spoke that I had never seen the nature of Western power and its narcissism so directly (if rather subtly in some ways) dramatized in any piece of African mainstream fiction.

For some reason that’s hard to pin down, African comics seem to find it easier to be direct about colonialism and continuing injustices. Perhaps it’s the in-your-face populism embedded at the core of comics.

Maybe it’s that mainstream prose fiction has its roots in English, in the social status of English, its social privilege, and the sheer difficulty of being bluntly political when your model is Jane Austen.

There ARE political SF prose fiction stories. I’m thinking of ‘The Sale’ by Tendai Huchu in AfroSF in which Zimbabwe the country has been sold and the Great Zimbabwe itself is being dismantled for export.

But comics more often and more unambiguously make political realities and nightmares into fiction.

Comics came SOONER to Africa than almost anything other form of SFF. Mighty Man was published in South Africa from 1975. Ibrahim Ganiyu self-published in the 1990s. Papa Mfe’empo in 1990s Congo published off-the-wall comics that were taken as political allegories. Tade Thompson in a video interview spoke fondly of the Japanese anime series Voltron, broadcast on Nigerian TV when he was young. It could be that superheroes being more available and impactful sunk deeper into young souls.

Tade Thompson is one of the two co-authors of The Last Pantheon alongside Nick Wood. The novella is an example of a super-hero story in prose. The roots of the Yoruba hero go deep into the creation myth of the people. There is a sequence in which the South African hero tries to prevent the disappearance (in this story murder) of Patrice Lumumba. The Nigerian hero and the South African hero embody two entirely different approaches to African development. One is based on black power discourse and decolonization; the other values modernization and economic development.

It is also the only piece of fiction in this special issue to be drawn from either of the two volumes in the AfroSF series of print and e-book anthologies, the works that, in the West at least, established that African SFF had arrived.

We’re also proud to reproduce in its entirety Khamzila’s Adventures from the Ordinary Superheroes series from South Africa. The series takes real people of accomplishment from the townships and turns them through fantasy into another kind of powerful hero. This story is based on the mountaineer Monde Sitole, who provides the afterword to the comic.

A softer kind of politics perhaps, but then as we shall see in Part Four, South Africa is a unique case.