From a distance, Idris Khan’s newly commissioned wall drawing in Whitworth Art Gallery, with its etched, ink-colored surface, resembles something akin to an elongated whorl, or a flattened animal pelt—if on a monumental scale. At closer observation, one discovers the image comprises lines of text, repeated and overlaid, and printed using a rubber stamp.

This is not Khan’s first exhibition at Whitworth. His series of drawings, 21 Stones, exhibited here in 2012, were his first foray into images made up of stamped lines of text, according to Whitworth Director Maria Balshaw. The Devil’s Wall (2011), prompted by grief from the loss of his mother and his wife’s stillbirth, featured cylindrical sculptures with texts from the Quran, in English and Arabic.

The son of Welsh and Pakistani parents, and a native of Birmingham, Khan was born in 1978 and trained at the Royal College of Art (2004) in London, where he now lives. Not surprisingly, solo exhibitions have been featured at prestigious galleries across the globe, from The British Museum (2012) to Gothenburg Konsthall, Sweden (2011), from the Guggenheim Museum, New York (2010) to Martin-Gropius Bau, Berlin (2009). Permanent collections include some of these sites and others: The National Gallery of Art, Washington; the Tel Aviv Museum of Art; the Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris; and the de Young Museum, San Francisco; among others.

In this current Whitworth exhibition, Khan draws on the work of significant artists and thinkers of the modernist period—from Stravinksy to Malevich to Nietzsche—alongside Islamic texts and words. The Rite of Spring (2013) digital C type mounted on aluminum, features layered photographs of Stravinsky’s entire score of the same name, whilst Beginning or End (2013), black gesso ground and oil relief ink on aluminum, serves as a meditation on Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy, as well as the cycle of life/existence. Eternal Movement (2012), digital C type mounted on aluminum, evokes the Hajj pilgrimage, in which devotees travel seven times between the mountains near Mecca.

‘Repetition is something my work addresses,’ Khan writes in his exhibition catalogue essay, ‘The Death of Painting’. The title references Khan’s own oil stick works featured in this exhibit, The Death of Painting 1-5 (2014), a series inspired by Russian artist Kasimir Malevich, whose painting Black Square, in 1915, would significantly influence art history—let alone artists like Khan. Ironically, Malevich’s single, black square painting, aimed at announcing the death of painting, inspired Khan to ‘make a series of paintings about the very fact that painting will never end’.

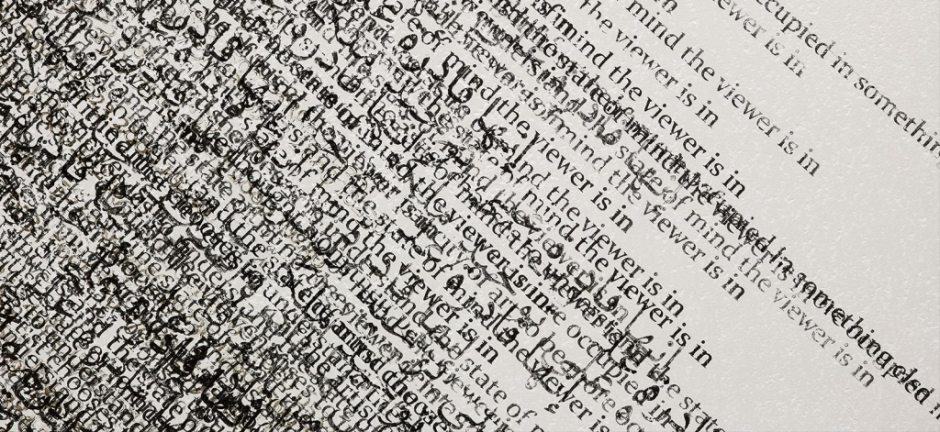

The tension between what will end and what never ends is born out in True Belief Belongs to the Realm of Real Knowledge (October 2016), Khan’s wall drawing, oil relief on gesso ground, produced onsite at the Landscape Gallery in September 2016. The wall will be painted over upon the closing of the exhibition, evincing the transitory nature of some of Khan’s work. Writing of his reliance on texts, Khan notes: ‘There one minute, gone the next, rubbed away and forever lost’. Indeed, ‘Loss, trace, the past, abstraction, repetition and the condensement of time, and of course, appropriation’, are words by which Khan defines his own work, he acknowledged in his 2010 Artist Talk at the Guggenheim.

But it also could be said that Khan’s work celebrates the importance of the fragmentary, given his pieces are constructed by layering fragments of texts and digital reproductions of musical scores, physically overlaid onto the canvas—or directly on the wall, in the case of True Belief Belongs to the Realm of Real Knowledge.

‘I’m not a writer, but I like the way words accumulate. If you place words on top of one another they eradicate the words underneath and this questions whether the word is destroyed, or by repeating it, gives it a more powerful meaning. It now longer becomes a word, it becomes a trace of time’. Elsewhere, he recognises, ‘the words no longer mean anything, they get lost between the layers and become, well, just paint’.

If ‘[f]ragments are the only forms I trust’, as Donald Barthelme’s narrator notes in one of his novels, Khan’s paintings may well represent another form of artistry that devotes to the fragment a measure of the enduring, even while recognizing the very transitory, if inspiring, nature of that fragment.