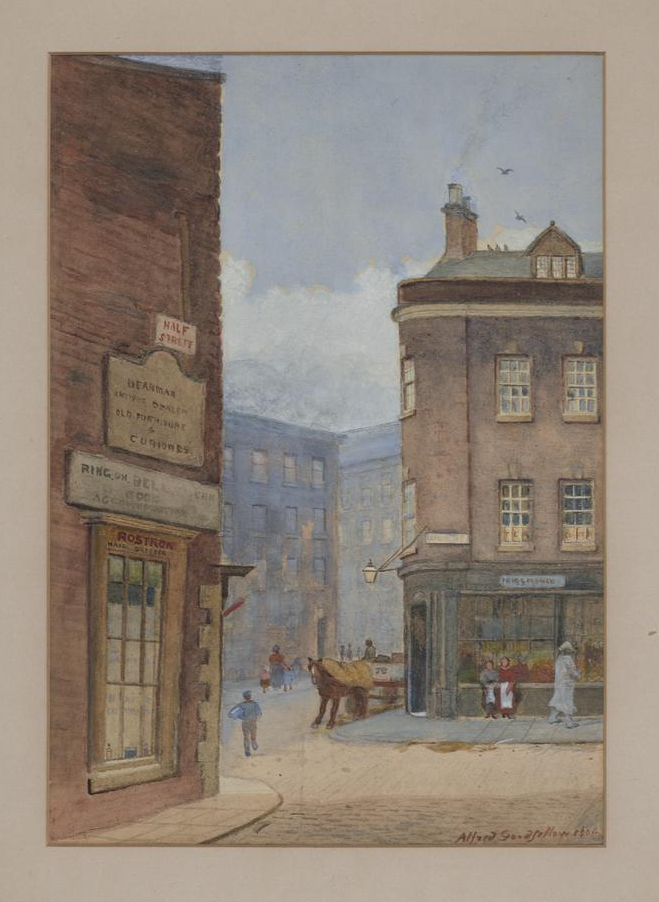

Image: © Courtesy of Manchester City Galleries

I don’t know when it started. I, for one, have never been that interested but it’s happened that gradually, over the years, as our life together has become ever more uneventful so our desire to discuss politics has increased.

You could argue that it’s not surprising given the fact that for the past few years we’ve had an especially dysfunctional government which means there’s always plenty to talk about, but I’ve noticed that the more disruptive and incompetent the government, the more calm and appealing our life together feels.

Only this morning, having read about the Prime Minster facing his third vote of no confidence, I came downstairs to windows full of a soft grey light and sofa cushions still neatly plumped in the positions I took the trouble of putting them into last night, and felt as if I were entering a great peace.

We don’t read novels or watch dramas anymore, relying instead on this particular administration to provide all the entertainment we need. Something will always be happening. It’s as if the people in power will not survive unless it is, even if it’s bad – in fact especially if it’s bad so we can react to it, ideally with outrage. We love to be outraged and the worse the thing the more satisfying our outrage.

– It’s disgusting, we say, appalling, it’s just incredible!

And when we’ve run through our gamut of such phrases and forgotten them we go back and use them all over again. It’s useful that we forget quite easily these days. The words we use to express our outrage always feel fresh which means our outrage itself feels continually, outrageously, fresh.

– How simply fucking awful they are, we say.

We like to say ‘fucking’ a lot when we talk about politics. We like how its hint of violence never fails, no matter how many times we use it. And I like to say ‘lurch’, as the journalists do when they describe the way the government ‘lurches’ from one crisis to another. I like how it makes me feel, by contrast, very much in control of my own movements as I go about my day, moving this and that – the cushions on the sofa, for example.

When we tell each other stuff, like some contentious new piece of legislation we’ve just heard about, there’s an intensity in the way we look at each other. We see reflected there our own anger and disbelief. Something is happening, not only miles away in the corridors of power but right here at the kitchen table. We feel strongly, we like to feel strongly. We like that we feel strongly without feeling the need to change anything about our life together which is, it must be said, pretty comfortable.

Take lunch, for example, a simple but nutritious meal, made not so much out of hunger as to mark a brief functional pause in the middle of our day.

I place a bowl of salad on the table.

Hard rivers of white in the purple cabbage.

Golden pool of oil.

I know exactly how the rest of the day is going to pan out. I think about the bed I made this morning. I feel almost virtuous knowing it’s already made, that I made it, that it’s waiting up there, that it’ll wait all day for when I return to lift the covers and slide back in.

We eat, take an occasional sip of water. The silence is fine to begin with. You might even call it companionable, each chewing our mouthful, thinking our own thoughts. But as the meal proceeds the silence grows and the larger it grows the smaller we become inside it and inside us, even smaller, each of us alone and somewhere inside that some tiny flapping thing I can hardly see.

And I have a horrible feeling that this is it, that we’ve said all there is to say to each other, that in this silence that expands, that fills itself, nourished by its own wordlessness …

– Those boats, he says.

– Don’t, I say, holding up an oily knife, don’t get me started.

When what I want is, precisely, to get started on something, anything, other than this meal and its terrible radiating silence.

– Did you see about that immigration bill? I just can’t –

Our eyes lock together. Something is happening at last, as our attention turns to the Home Secretary who we like to call ‘catastrophic’ and, by extension and with a sense of collective responsibility we try to feel, to our failure as a country to become a destination for a better life.

Whatever you might be thinking about our life together, it cannot be said to be chaotic or unruly. We’re not vengeful, we don’t need to score points or shout at each other across the room, as they do. In fact we want nothing to do with those people’s cynical and manipulative shenanigans. That’s not strictly true. We do want something to do with them, we want to hear about them so that we can talk about them and feel ourselves to be properly informed. How is anything going to change if we don’t keep ourselves properly informed?

Anyway, the point is that we know all there is to know about our life together which is maybe why we don’t feel the need to talk about it. What is there to say about our neatly-made bed, our humble lunches, never mind our relationship? In fact, it occurs to me that we talk more about the relationship between the PM and the Chancellor than we do about ours.

I watch as he lifts both glasses with the fingers of one hand and the water jug in the other and walks to the kitchen. I take his plate and stack it on top of mine and sit there a moment, looking out the window.

We speak about other things of course. The birds, for instance, which he loves to identify and talk about in great detail. Sometimes I do too and we discuss what we’ve seen on the feeder. Once, a very rare bird appeared, which got us quite excited. We asked questions about it we knew the other wouldn’t be able to answer. I think it was a surprise to us how happy it made us, how much we wanted it to come again. For a while we were full of expectation as we stared out the window but I grew tired, a great weariness came over me. All I could think about was the bed waiting for me, the one I had made. I climbed the stairs telling him that I’d look out for the bird from there, knowing that our bedroom window was only ever full of sky in which no bird could ever land. But I liked knowing he was downstairs, looking out. I liked knowing someone was there waiting, with hope.

____

Greta Stoddart has written 4 poetry books and a radio poem that have each been shortlisted for the Forward, Costa, Roehampton and Ted Hughes Awards. She is also a winner of the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize. Her latest book Fool was published by Bloodaxe in 2022. She won a Cholmondeley Award in 2023. She lives in Devon, teaches for the Poetry School and is currently working towards a collection of prose.