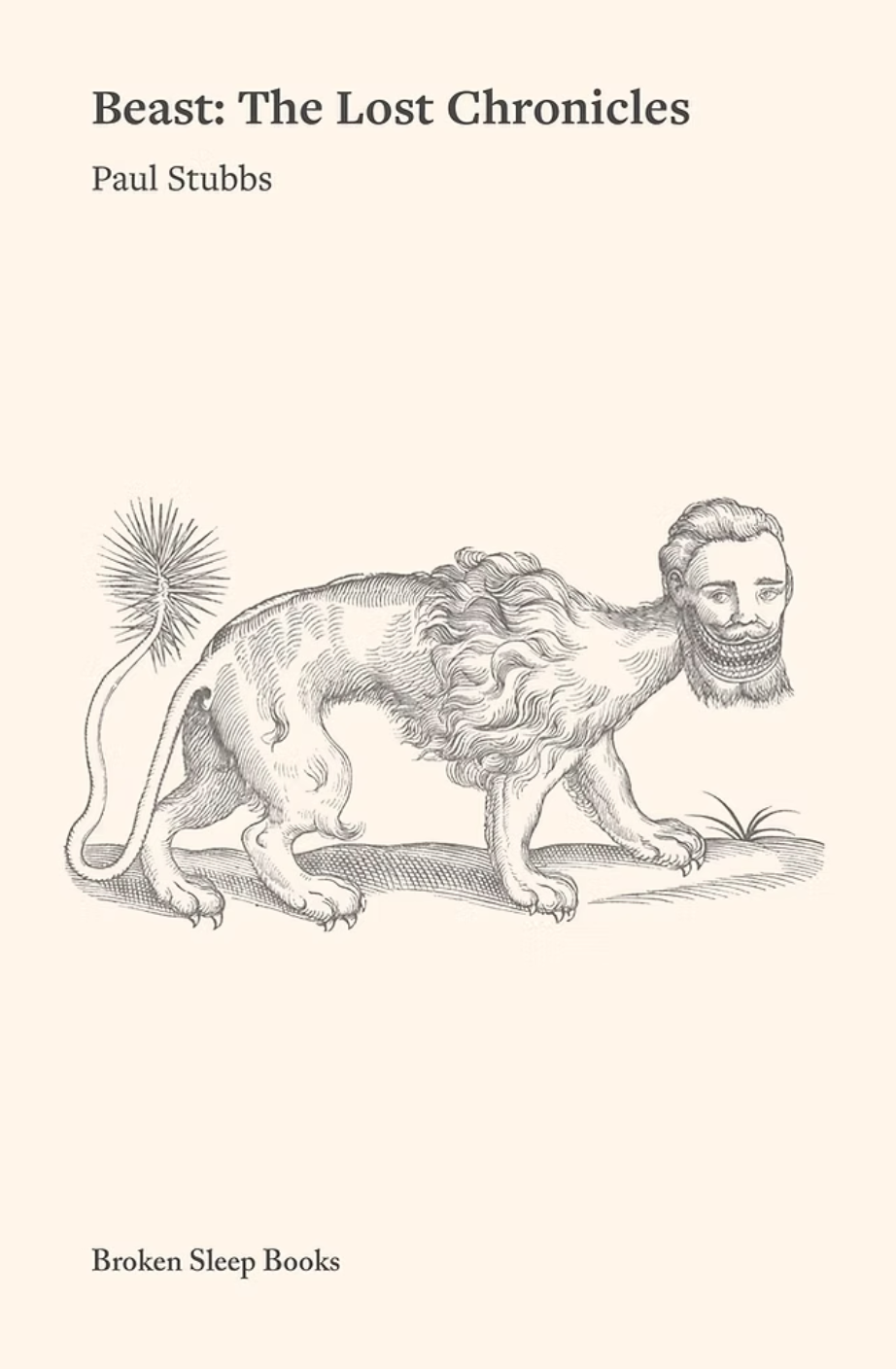

A potent and challenging poetic reimagining of Yeats‘ ‘rough beast‘

Paul Stubbs | Beast: The Lost Chronicles | Broken Sleep Books: £9.99

Reviewed by Michael Lee Rattigan

‘En route to Bethlehem’ contains the first of many cleavings in Paul Stubbs’ propulsive seventh collection, in many ways both a culmination and a confluence of this poet’s singular work. Here the beast ‘slouches’ free of the apocalyptically resonant poem in which he is birthed and takes on new life in Stubbs’ imagination. Note the immediate physicality of this incarnation, with the beast ‘plunging’ into the Irish sea before making a beeline for Ben Bulben ‘where one religion later, / we catch up with him, slumped / against the gravestone of Yeats – / horrified to be left alone…’. This abject desolation and sudden realization of orphanhood is a pivotal starting point, though the beast isn’t prepared to take anything lying down, intent as he is on cindering every last page of recorded text in which his own name isn’t uppercased.

In many poems Ted Hughes’ Crow (1970) is brought to mind, alongside European poets such as Zbigniew Herbert and his Mr Cogito (1974), as in Stubbs’ poem ‘Trying to become God’. Here the beast loses no time in playing havoc with ‘God’s own pre-creational cables’ in order to switch on – as he’ll later switch off – ‘the first light-filaments of stars’. And, instead of Hughes’ ‘Examination at the Womb-Door’, in ‘The Beast attempts to be Saved’ we are faced with a series of notes (scribbled down by God) that quite literally nail the unsalvageable nature of the beast:

Any underlying symptoms of redemption to note?

No…

Any neighbourly compassion for his fellow beasts?

No…

Growth of a second tongue and/or mental imbalance?

No…

Any significant new damage to his heart tissue caused by love?

No… nothing

Only the six-inch retractable bones now jutting out

from each paw where Christ’s nails could have been.

It is in such irreconcilability and desperate bafflement that these poems come into their own, just as in Crow, though in this collection the soteriological (or salvational) dimension is at the forefront and, instead of Hughes’ universalistic, even occultist tendencies, a more philosophically and theologically steeped imagination is at work.

The philosophical content is here, as throughout all Stubbs’ work, grist for the poetic mill – allowing for a leap through the needle’s eye. This makes demands of the reader, though only in ways that this reviewer believes are urgently necessary for contemporary British poetry. Stubbs’ work calls to mind Eliot’s refutation of ‘little Englanders’, and Al Alvarez’s attacks on the ‘terrible English’ poetic gentility, he who, in his pivotal book The New Poetry (1961), cleared a path for poets like Hughes and Plath.

The only poem in which the beast speaks for himself is ‘Extracts from The Beast’s Logbook’. Here he appears as literature’s ultimate shapeshifter, poised to ‘miscarry him, Yeats’ but not before the ‘miscarriage of mankind’, as glaringly stated in the logbook’s 11th entry:

This morning…drinking the blood of men not holy enough to resist me. Using the eye-sockets of their skulls as if binoculars, seeing a mirage of myself, on the horizon, eating God. What omen is this? What hour arrives?

The question of the beast’s lineage snags every nerve-end of this ‘lapsed Christ’, who begins to suspect (indeed fear) that he may be human after all. This vulnerability is reversed in the poem ‘A New Account of the Trinity’, where the three-in-one come looking for the beast to become their ‘elusive fourth part’, in order to ‘join up…and make them feel whole’. Is this the wilderness in which ‘God’s soul’ at the close of the poem is dragged, or somewhere else? Whatever the case, the 13th entry lays bare a desolation amid desert sands that makes even Eliot’s Wasteland feel comfortable, even plush, in comparison:

Half buried in the sand up ahead of me, an altar of incense, smoking. A blindman feeling for my soul in braille. His fingers bleeding. Two of the trinity bandaged and limping and refusing to meet my stare. Flies, in broken ranks, failing theologically to negotiate my shape.

Such biblical mangling extends, of course, to every last character in the Bible. Elsewhere we find the beast ‘tooth-picking the last rotting entrails of angels from between his molars’, before wormhole-ejecting ‘all biblical characters to another galaxy, and a different role’. Yet the visionary reckoning of these Chronicles seems to tread on the toes of Kierkegaard’s ‘Knight of Faith’, taking everything back as he does ‘on the strength of the absurd’. The beast embodies an embrace of absurdity, who, for all his inchoate thrashing, tries

each epoch to regurgitate the drafts of any one document that,

if read might possibly have

stopped genocides, invasions,

fake cults, religious wars etc…

might above all have stopped

evil hatching in the human heart

So that we are able to say, by the time we reach the ‘Epilogue’, in which the beast is ‘pockmarked with the welts / of a world’s worn words’, and where a falcon (inevitably) lands ‘on the wrong wrist’, that the poems in this collection lie in wait for the last act of faith to appear. One feels that Yeats, determined as he ever was to ‘remake’ himself, would delight in the potency of this work and what Stubbs has made of his rough beast.

Reviewed by Michael Lee Rattigan