Contemporary Bulgarian fairytale told in a polyphonic, experimental style

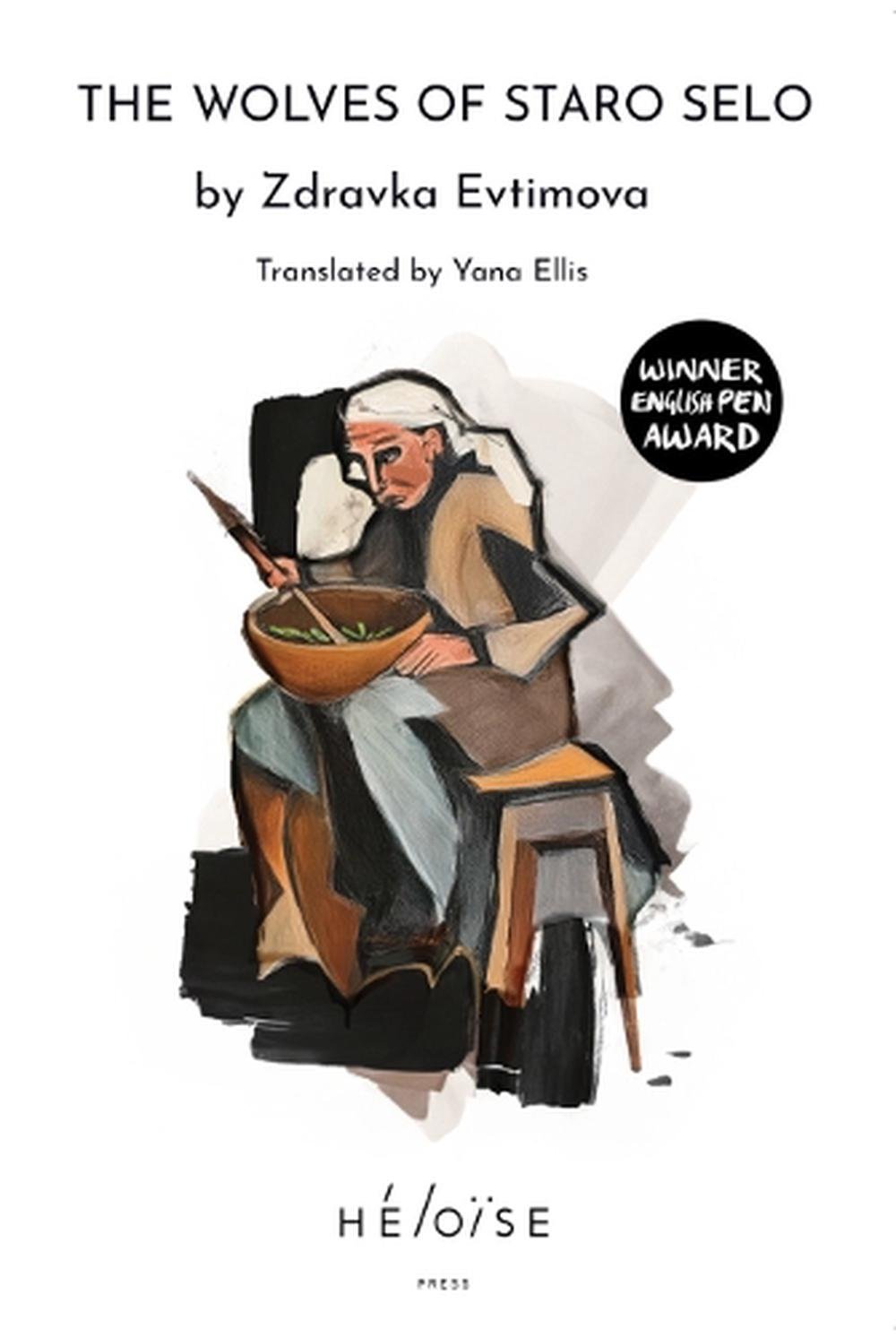

Zdravka Evtimova | The Wolves of Staro Selo | Héloïse Press: £12.95

Reviewed by Dylan Stewart

The Wolves of Staro Selo is a contemporary Bulgarian fairytale told by Zdravka Evtimova, who won, among other accolades, Bulgaria’s Favourite Writer in 2021, and translated by Yana Ellis, who won the PEN Translates Award for her work. It is apparent, even obvious, why Ellis deserves praise for her translation, even as somebody not familiar with the Bulgarian language or Evtimova’s other work. The voice and style of the novel is strong and varied; to get across both Evtimova’s moment-to-moment word play and the experimentalism that animates the novel is an impressive achievement.

This style is what, for me, made the novel a joy to read. The effects of the prose style snuck up on me through Evtimova’s use of both variation and repetition. I began to notice something when the novel shifted between three distinct voices in the first 38 pages and then shifted once again to a detached third person, like a stranger telling you a folk-tale across a campfire, or a good Gogol story. Evtimova has a talent for odd phrases which she often uses, to great effect, to describe the same thing – usually characters – in new ways. For example, when Ginger Dimitar, a bandit and villain of the work, enters a scene he is most often described not as “Ginger Dimitar” but instead as a walking flame or a disagreeable carrot. This, despite distancing us from the characters, actually makes them more familiar as we can recognise them by their image and not just their names. As well as comparing people to objects and animals, Evtimova repeatedly personifies objects and phenomena:

Once, a long time ago, when summer was still young and couldn’t clamber past June and couldn’t find the heat and was basically still spring with rains

Both of these techniques work in unison to make the world seem both magical and human. What the above quote also shows is the expressive, inventive, and yet slightly childlike nature of the voice. This allows the work to be stylistically complex, filled with metaphors and similes and shifts in location and voice, without ever getting bogged down or hard to follow. It is a novel that is doing a lot and makes you aware that it’s doing a lot, but that never makes reading it become a burden.

The content is about life in 21st century Bulgaria, and much of it is about the poverty and insecurity that are, unfortunately, part of life in that country. It is also a multigenerational family story that depicts the lives of everyone in that family as a three-dimensional human being. When Elena, the witchlike folk healer and grandmother, is introduced she seems an almost mythical figure, but over the course of the novel we learn that she was once a young, gangly girl who couldn’t dance and burst into tears when her future husband said that he wouldn’t go out with her because she was taller than him. Although a lot of the novel is about the experience of oppressive poverty and the fear and cruelty that it engenders, there are also descriptions of joyful parts of Bulgarian life: town-wide celebrations filled with drinking and dancing, love of music passed down from generation to generation, and a personal relationship with God.

It is worth mentioning that there is a detectable Christian conservative current running through the text. The villains of the piece are an adulterous wife and a violent bandit who both eschew morality and honest work in favour of material wealth. The heroes, by contrast, are virtuous and succeed because of their adherence to traditional customs and the strength of their family ties. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, and even where the novel is most conservative, there is empathy. Both the adulterous wife and her equally adulterous mother are voiced in chapters where they explain themselves and their actions. This illuminates their apparent selfishness: poverty and the lack of understanding shown for them by their community leads them to cynicism, and a need to escape their circumstances by any means necessary.

The story, in comparison to the characters and style, is fairly simple. It doesn’t need to be any more complex – perhaps if it was it would distract from the other elements. There are many sections which don’t move the plot forward in any significant way, but instead give us an increased understanding of the characters we are following and the world we are inhabiting. This approach until the end of the novel, which I found rather abrupt. I believed something more conclusive was coming and was surprised when it did not. However, this is a novel that, despite its fairytale style, has a certain sense of realism to it. It is a story about what real, messy life is like in Staro Selo, and life mostly lacks clear conclusions.

Reviewed by Dylan Stewart