It is an imagination, and a world, that I quite liked inhabiting. In some ways it seemed notably British, made up of well-meaning but somewhat sinister parochial towns, cities with draconian laws, a legion of nearly identical coppers to enforce them, and superstitious drifters who seem sick of the whole set-up but have no power to change anything and don’t even know what that change would look like.

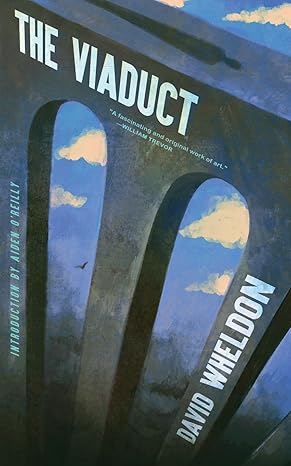

David Wheldon| The Viaduct| Valancourt Books: £13.99

Reviewed by Dylan Stewart

‘Something of value.’ That’s the phrase that keeps returning to me as I try to put my thoughts together about this novel. David Wheldon is the author of four novels, seven books of poetry and a short story collection. The Viaduct has recently been rereleased by Valancourt books, along with The Course of Instruction. The collection The Guiltless Bystander is also worth mentioning, being released shortly after his death in 2022. The Viaduct is not a well-known work and David Wheldon is not a well-known author, it has a total of twenty-four ratings on Goodreads, Wheldon’s other works have less. And yet, at the time of its release it received notable praise, winning the Triple First Award in 1983 and causing William Trevor to say that he remembered the book “vividly long after reading it”. It seems a shame to me that it was forgotten by the world more generally.

This is partially understandable, however. The Viaduct is, especially at the beginning, a rough work. The first two chapters contain many awkward repetitions and some clunky dialogue, for example: ‘Down below the noise of the bells had stopped, and the city was silent with a Sunday silence. In the city beneath the viaduct the towers were silent.’ Phrases like these give the impression that the author is unsure of himself, a sort of literary stuttering. However, as the work goes on these abate, Wheldon finds his stride and the style becomes enjoyable, at times even beautiful: ‘The moon had, as it were, shaken itself free of the cloud and had risen in the sky. The hills beyond showed, with a silver beauty, their rounded summits and their shaped valleys. The range of hills stretched across the horizon and their distant splendour seemed to be both ephemeral and timeless.’ This is only my reading of what goes on in these opening chapters, but I mention it because this perception of the workings of the writer formed a large part of what I valued in the work. Wheldon seems to constantly get compared to Kafka, I’m not sure what I make of this comparison, but I do think my experience with these authors is similar in one key respect: a feeling of access to the author’s personal creative process through their work. I can imagine, whether through delusion or empathy, both of these authors trying to transform feelings I myself have felt onto the words I see on the page. This empathy with the author goes a long way to make me forgive what I see as mistakes and praise wholeheartedly what I see as achievements. It is hard to explain how this effect is created but I can try.

The plot of The Viaduct is very thin with chapters only loosely connected and characters disappearing and reappearing at random. This creates the impression that the book is not a traditional story in which all the pieces fall cleanly together into set-ups and pay-offs, themes and character arcs, but instead that something more freeform and unconscious is going on. Despite the lack of plot-structure, there is a character to the work, symbols and motifs recur: the coldness of travel, uncertainty of one’s own identity, untrustworthiness of other people, sights of hills and the night sky. All of this together creates a particular atmosphere that unifies the work and gave me the impression of access to the imagination of the author.

It is an imagination, and a world, that I quite liked inhabiting. In some ways it seemed notably British, made up of well-meaning but somewhat sinister parochial towns, cities with draconian laws, a legion of nearly identical coppers to enforce them, and superstitious drifters who seem sick of the whole set-up but have no power to change anything and don’t even know what that change would look like. All of this can also be interpreted more generally. When the pastor, mayor, and magistrate of a town (all one person) tries to convince the drifter protagonist ‘A’ to stay with promises of work and disparagement of the life A is living, it gets at a more universal experience of being encouraged to give up on one’s ill-thought-out dreams for the safety and comfort of a more mundane life. These expressions are not only relatable but valuable.

The work, despite its initial roughness and philosophical bent, is very easy to read. There is a clarity and straightforwardness to its style which make it immediately understandable. It’s also quite short, which is a shame, it could have gone on for longer with little problem given it’s loose and fragmentary structure. In fact, my biggest issue with the book is that is that it doesn’t seem to be long enough to fully explore its own themes, world and thoughts. It never quite seems to say what it’s saying. However, in a way, this is a good problem for a novel to have. It has left me wanting more.

Reviewed by Dylan Stewart