An unreliable narrator’s cry for help

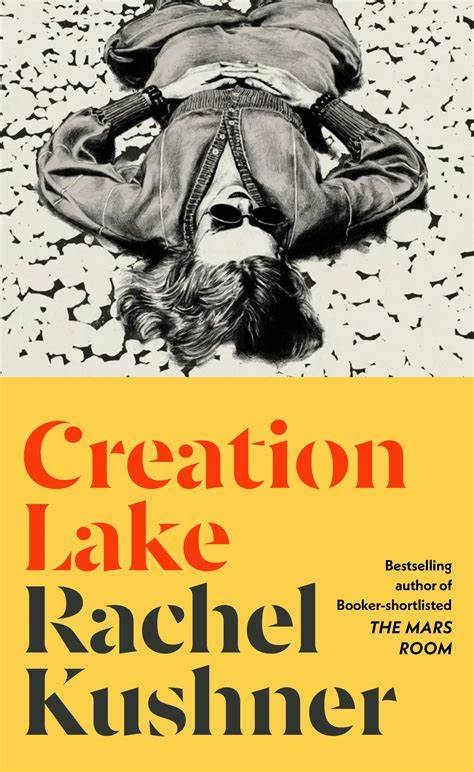

Rachel Kushner| Creation Lake | Jonathan Cape: £18.99

Reviewed by Georgina Parfitt

My friend and I happened to be reading Creation Lake at the same time without knowing it. I mentioned it one day, withholding my thoughts, and my friend got excited: Oh, you too?, We hesitated. There are elements of Rachel Kushner’s latest novel that seem… well, sort of bad. Or, they might be bad. We’re led by a narrator who is almost cartoonishly unreliable, a persona who is very aware of her own breasts as instruments of espionage, for example. (“I laughed, my own implants barely contained in the triangles of my white bikini.”)

The sentences in Sadie’s voice have a clumsiness to them, the way she says “implants” instead of “breasts” even, forcing us to imagine silicon shapes in a bikini, a messy illusion. And other examples, too, “the clang of a church bell heard from a distance, et cetera,” might suggest that we’re reading a spy novel with a speaker who is jaded about “real life” in that typical, spy-novel way.

And, yes, the book is full of unreal relationships. In fact, Sadie’s success (read: persistence) as an undercover agent seems to have a lot to do with her undoubted ability to seduce. Relationships are Sadie’s way into a job. However, counter to our expectations of the unreliable narrator (this persona that has become, actually, quite reliable), Sadie’s relationships are not complete charades. If she’s supposed to be a femme fatale, enticing otherwise smart, streetwise-ish men to fall for her, she plays this role awkwardly. She entered the world of spying accidentally, after getting in too deep with a group of bikers, and from this uneasy starting point, her career progresses in a series of stumbles. The word “job” is so synonymous with “relationship” that by the end of the book, when we hear of Sadie “turning down all offers of work,” we know that she has also turned away from men.

There are some tropes in play (the spy losing control of the cover story, those familiar slippages of the unreliable narrator, the piecemeal construction of scenes-as-clues). And yet, my friend and I both liked the book – tore through it, were gripped and interested – and we both found Brandon Taylor’s review in the LRB frustrating (the review is titled, pretty rudely, “Use your human mind!”). In the review, Taylor despairs of the book’s “careless construction and totalising cynicism.” Yet, he seems most upset by a more general shoddiness, an affliction shared by too many writers today – “Shallow, rapidly swirling narrative consciousness has come to define the refugees of the Attention Span Wars,” he writes, and Kushner’s novel is made an example of. “Why did you even write this,” he asks, but the question feels like it’s directed beyond this novel in particular. Why does anyone write anything?

The despair in this critique reminded me of Anne Haverty’s recent essay, “Writing In The Stupid Age,” a kinder point of view. “Can we write anymore about people?” she asks. “Can’t we only write about phone-people? Writers may be asking themselves this question, as more of them abandon what looks like barren ground and turn instead to writing about the past.”

My experience of the book was not one of totalising cynicism, and my experience of its narrator was neither one of a stupid person nor of a person playing dumb (as Taylor suggests in his review). Instead, I encountered a person numbed, dissociated, but also sad. Sadie’s veils are faulty, her wiles are limited, she cannot, James Bond-like, simply soar into a new mission anchored by a familiar cocktail order. Sadie drinks whatever she can get hold of, she shares information inelegantly, even the fiancé she’s manipulating cheats on her in the end. If she seems like a relic of an unkind tradition (both literary and cultural), she is by no means a perfect example of an inhuman double agent.

Sadie has signed off from the authentic, the moral, the actual, gone off-grid, and yet, in drawing her, Kushner keeps an eye on need and pain. The experience I have of Sadie is of a person very far gone but not quite disappeared, even when she seems to move deliberately further and further from the trappings of real relationships through the course of the novel (even to the point of retiring to an invented town named after a signpost, Priest Valley). We are lonely in the “stupid age” and we can’t actually disappear, even if we near-drown ourselves with screen-life and avatars.

It is not an accident that the novel lands somewhere quite sentimental. Throughout her mission, attempting to befriend and betray the radical group Le Moulin, Sadie describes the world around her with an uncomfortable detachment. Even her metaphors seem to be selected from a narrow semantic realm: “I passed a tower on a cliff, its top edges eaten away like a sugar cone.” In her own words, a “tasteless container.” Sadie can only liken real things to… less real things. She thinks down, not up. But when this person, who has led us through numerous fake relationships leaves us, she is looking up at the sky, stargazing. There is wonder and hope in Creation Lake. While it may not rest in the French village square or in the arms of a new lover, or even in the project of communism, it does appear via the long, tangential emails of Bruno Lacombe that Sadie drinks up, with their Neanderthal facts, their water, darkness, cave paintings, voices, fire. The wonder happens – yes, in a difficult, roundabout way – but it happens; we may be “stupefied,” as Anne Haverty (and perhaps, Rachel Kushner) would suggest, not stupid.

Reviewed by Georgina Parfitt