Lost and found are two sides of the same coin in this stirring tale of desire

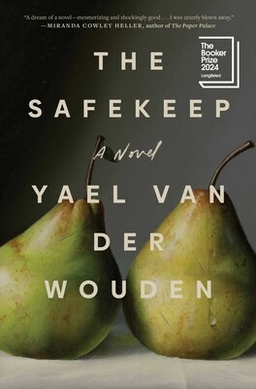

Yael van der Wouden | The Safekeep | Viking: £16:99

Reviewed by Alexandria Mowrey

‘They are not for touching. They are for keeping.’ These are the first words spoken by Isabel in Yael van der Wouden’s Booker-shortlisted (and debut) novel, The Safekeep. We meet Isabel living alone in her childhood home, her mother dead, and her brothers elsewhere. By definition, she is quite lonely, but her occupation with maintaining the upkeep of the house, from the chinaware to the garden, fills her days and consumes her every waking thought. She holds the home close, wearing the badge of keeper and guardian, a self-given one at that, with unbridled pride. We learn early on how this pride clouds her judgement, impedes upon her ability for social interaction, and paints her as compulsive, cold, neurotic. There appears to be no Isabel outside the context of the home. Her debatably parasitic relationship with it, informing her character and thus, the foundation of the novel.

The most frequent adjective reviewers have assigned to the novel is “thrilling.” Now this is not the “thrilling” loaded with promise of riveting action that teeters on the line of danger and fright. No, the definition that van der Wouden employs is far silkier; Nestled somewhere in between haunting and arousing. She is more interested in blowing cool air down our necks, tracing her finger up our forearms, sending goosebumps down our skin. The delicateness with which she navigates through the story, as if tiptoeing through the dark hallways of the very house in which it is set, is a large portion of what makes up the story’s descriptive nature.

Told across three acts, the novel uses each section as an opportunity to deconstruct the hard exterior in which the story is housed. In the first act, we see the wallpaper peeled back when Eva, Isabel’s brother’s new girlfriend, is forced to stay with Isabel for an extended period of time. She barges into Isabel’s life with her bleached hair and abrasive friendliness. A foil in every sense of the word, her arrival brings a whole new host of change to Isabel’s priorly mundane life. She makes a mess of Isabel’s mother’s room, items around the house begin to go missing, the maid gets invited to stay for wine, and the two women clash at every turn. And yet, the most repulsive thing Eva does is the very thing that has been absent from Isabel’s life thus far. She introduces and validates desire as more than just an emotion but as an action.

When van der Wouden speaks of desire it is a thing of its own, “a blurry shape turning sometimes sharp, a loud Klaxon of yes; and answering the question Where? With: Anywhere. Anywhere.” This may be one of the greatest strengths of the novel: the way it presents want as an autonomous being, individual from the self. This perspective allows the novel to then become an incubator for desire (apart from providing safety and protection to its inhabitants, that is). Characters like Isabel are ravaged by want, obliterated by the inescapability of it. She wrestles with it constantly, unable to find refuge. You can make the case that the novel declares want, desire, and longing as futile. Nihilistic in the way they morph and warp the reality in which the characters exist: Forbidden desire for the physical body; Uncontrollable desire for control; Hopeless desire for belonging. All are at play and all force their participants to reach utter destruction and desperation before there is any resolve. But that is often the secret ingredient, is it not? For a resolution to feel earned, there must be the illusion of a final, irreversible end, a whiff of death. On Isabel’s transformation, van der Wouden says, ‘I wanted to rip her open at the seams.’

By the end of the third act, van der Wouden has indeed ripped Isabel open at the seams. With her follows Eva, the house, the plot, and then ultimately, the reader. The walls of the story have been torn out, drywall exposed, infrastructure hanging out in the open. And yet this demolition is performed so stealthily. The novel is deceptive in that way. With its tight plot and delicate thrills, The Safekeep is able to conceal a deeper, richer message residing beneath what we initially believe the story to be. Like nesting dolls, when one is opened, another is revealed, and another, and another.

This is a novel whose contents linger with you long after you’ve finished reading, resting on the tongue like tannins. It remains an incessant reminder of the malleability of truth and how the stories that carry it rarely are just one thing. And so, this taste remains, unyielding, leading you to wonder if you really did notice everything on the page. Or was there something else, just there, hidden in plain sight all along?

Reviewed by Alexandria Mowrey