A narrative of life, death and the intrigue encompassing both.

Charlotte Wood | Stone Yard Devotional | Sceptre: £16.99

Reviewed by: Stuti Dhar Chowdhury

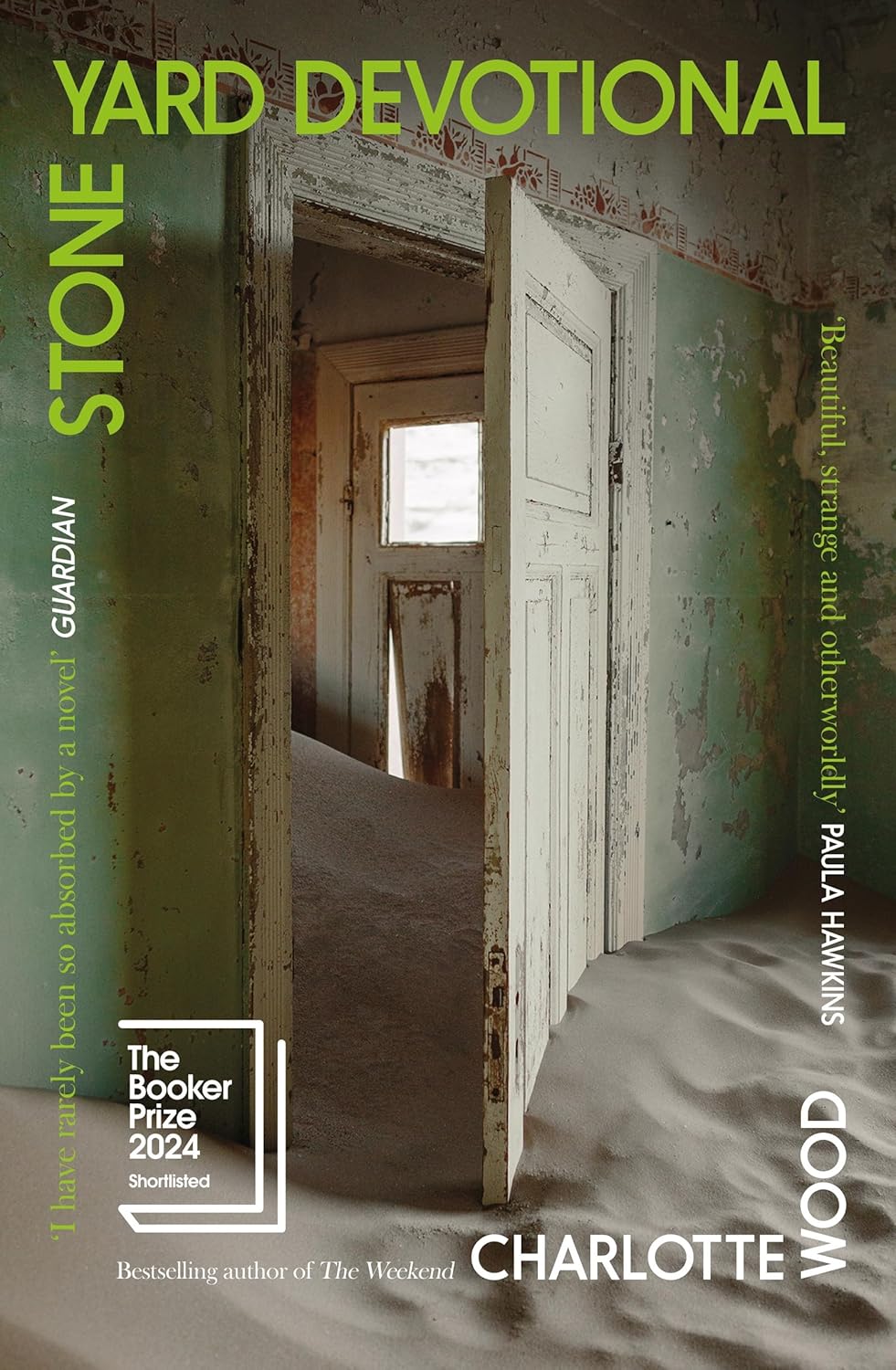

A novel which pulls you right in, and yet keeps you at a distance; Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional is a true delight to read, which explains its nomination for the Booker Prize this year. It’s a book encasing grief, burnout, a desire for human connection while grappling with the fragmentation of one’s own existence. The narrative follows a pattern of stream of consciousness writing which helps it achieve a non-linear, fragmented structure. The cover reads- “Beautiful, strange and otherworldly” which is an accurate portrayal of how the narrative leaves you feeling.

One has a lot of questions as soon as the narrative begins, and one ends the book with even more. The reader enters the novel in media res, and is instantly wrapped up in the ambiguity of the words. One can’t help but notice a deliberate attempt at birthing curiosity about the identity, past and origin of things being spoken about. If one didn’t know better, they’d perhaps think they started reading the novel from a point later than the beginning. However, this intrigue is beautifully unpacked with subtle callbacks and references scattered through the happenings of the novel.

The foremost theme of burnout and exhaustion expressed at the very beginning, is one that most can relate to. However, just as the protagonist can’t stop checking her phone for emails, neither can the reader put the book down. Beyond all social exhaustion and desire to be left alone in silence, there’s a pursuit for human connection, a deep, meaningful one which is gradually achieved through the course of the narrative. There’s a profound presence of the past throughout the novel; the past along with all its associated emotions, claws its way into the present to colour it differently. There’s a certain unpredictability in the pattern of things, which makes the oscillations between memories of the past and retrospections of the present, quite enjoyable.

The palpable sense of unprocessed, deeply-ingrained grief clouds the majority of the novel. The protagonist’s grief shines through not only the narrations of her own parents’ death, but that of many others that she’s known of in her lifetime. The reader can instantly recognise the other stories of death and loss being used as a kind of crutch for the protagonist to lean on, to help her process and feel through the grief of her own parents’ deaths. The idea of unprocessed grief is layered beautifully with a descriptive metaphor of mice infestation. The mice, described as eating away at its hosts, scurrying away silently, getting louder as the silence of the nights seep in, are conspicuously paralleled with the ever-present, unprocessed grief of the protagonist. There’s an almost amusing sense of movement of the protagonist through the 5 stages of grief with regard to the infestation. It is to no one’s surprise that the “plague” dissipates right after the bones of Sister Jenny are laid to rest at the end of the novel. The descriptions of the plague’s wrath leaves a bitter aftertaste as one visualises the gore and violence of the affliction within.

The novel is divided in three parts, which jump timelines between them. However, what remains constant is the protagonist’s reminiscent narratives of her own life and that of others. The loneliness and desire for connection begets a lot of contemplation on her part, about the people who came before her and occupied the same spaces as she does now. The slow and uncomplicated life of the Abbey helps her move away from the fast-paced, exhausting life that she ran away from. Thus, one can’t help but be faced with old stories, peeping from the unknown corners of her memory. The unresolved guilt of having been a bully to Helen Parry complicates her relationship and interactions with the latter. Moreover, her guilt for supposedly not being a better and more mature daughter is one that haunts her long after her parents are gone. Towards the end of the novel, she writes about ‘Forgiveness Therapy’, which makes one wonder if she can ever truly forgive herself for the mistakes she has made or thinks she has made.

Towards the very end of the novel, there’s a line which can act as a foil for the narrative itself- “Nobody knows the subterranean lives of families”. Moving from Sister Jenny and Bonaventure’s complex relationship, to that of Helen Parry with her mother, and that of the boy who shot his parents, the narrative focuses on the depths of human relationships and interactions that are much deeper than can be seen from the surface. This makes one wonder about the distance at which the novel places the reader, divulging profound information but perhaps not giving away the entirety of it; perhaps, holding onto the subterraneous truths about her relationship with her parents, with Alex, with Helen Parry. By the end of the novel, while the reader knows of the exhaustion, the grief, the guilt, one doesn’t even know the name of the protagonist, which leaves space for so much that is still kept at a distance beyond reach. Charlotte Wood’s Stone Yard Devotional is truly a tale of devotion; devotion to life, death and the intrigue that fills the gaps.

Reviewed by Stuti Dhar Chowdhury