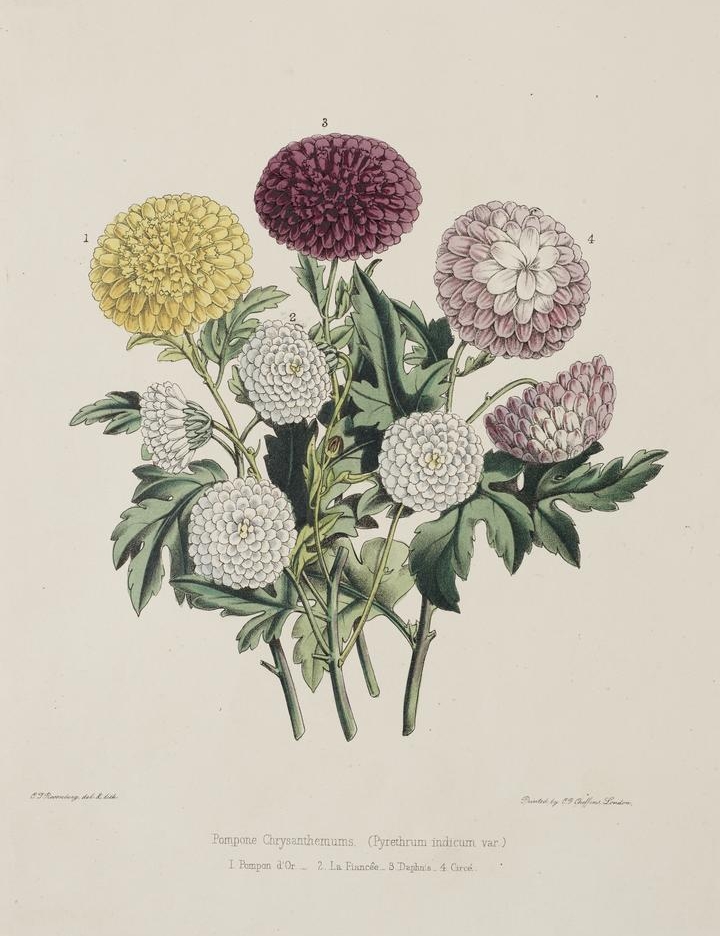

Image: © Manchester Museum, The University of Manchester

“Sex with my wife hasn’t been the same,” my lover says, “since her breast cancer.”

Where bedsheets retract, the shoreline of his body emerges. Lumps of burnt pink, freckled all over. Behind him, glass slats combine to windows, and then the Mediterranean, its green light stretching all the way to our ceiling. It is this ceiling that he stares at as he speaks.

“They offered her breast implants,” he continues, “but she refused.”

“Really?”

“Really. Now she has no boobs.” He reaches in for me. The skin of his hand is stained with sunspots. It sticks to my chest, to the semen not yet dry in its hollow. I picture the sperm, the million heads squirming into the crack of his palm. “Honk,” he says.

I close my eyes. I smell chlorex and must through the air conditioning unit, but no brine, even though we are close to the sea. The windows to this hotel room are a perfect seal – what they keep in, what they keep out, there is always a choice, and within each choice there is always a loss.

*

For dinner, I wear a long, backless dress. It was intended for formal events, and people turn as we walk through the lobby. My hair knotted to the crown of my head, my jaw stretched girlishly beneath my tan in a way it hasn’t in a while. In the mirror, as we cross the hall, I can only smile.

“You look wonderful,” says the man at reception. “You look wonderful,” says the waiter, showing us to our table. “You do,” my lover whispers in my ear, sliding the chair beneath me.

“Do what?”

“Look wonderful.” Then he adds, “I wish my wife would dress like that.” He raises his eyes to the ceiling, as if he were asking God for a miracle.

This is how my lover refers to her. On this holiday, he’s been calling her ‘my wife’, never by name. As he takes his place beside me, I draw her in my mind. The plumpy arms, the sickly tinge of her skin, the grey roots sprouting from her head that she forgets to dye. I know what she smells like, it used to be milk and honey but recently it’s drifted to a different smell, I couldn’t quite believe it was her but it must be, the smell is there when there is no one else around. Parched, soured. Middle-aged.

I know her well. I know her children. I’ve eaten food at her dining table.

The waiter stands above us. I cradle my face in my hands and look at my lover who is ordering the drinks. I know he likes when I look at him this way.

Every night here is almost the same. Vodka tonics, two rounds with our appetizers. A bottle of white with the main course, always white, it’s too hot for anything else. After our meal, we’ll have espressos and another drink. This last one varies, it’s good to vary a little when you’re on holiday with a man who fucks you in the ass and recites his wife’s annoying habits to you afterwards.

When the food comes, it’s simple reds and greens, traditional for this corner of Mediterranean. The hotel restaurant is simple too, white and anonymous, tall ceilings and an absence of decoration. A package-holiday hotel trying to be something it is not, a cheap luxury that might’ve been convincing in the years after it was built but it’s been a long time since. Now, there are only walls bloated with humidity, the echo of cutlery from its guests.

He picked this place because he could afford it. I suppose he could afford anything, really, but this won’t dent his family’s finances: he won’t have to sacrifice the school fees or his financial investments; his daughter’s swimming lessons, his son’s football camps, his wife’s private appointments. Our legs touch beneath the table; the vodka slides through me in a reassuring burn. Places like these, I think, exist only to shift the rest of life from focus.

After dinner, as usual, we are too drunk to walk. We lay on sunbeds in the dark. The tide is weak, the brush of waves blends with the bristling pines behind us. We light a smoke and touch each other like teenagers. I hold his earlobe between my teeth and let him tell me what to do.

*

He falls asleep before me, he always does.

From my side of the bed, he is no longer spinning. The crescent of his face is still in the moonlight. His nose pressed to the pillow: a perfect edge, a perfect angle. In the beginning, I used to stare at that nose for hours. I used to run my fingertip along it. I used to wonder about the geometry of nature; about all the impossibilities held within it.

Beneath the thrill of the air conditioner, I listen for his breath. The quiet heaves and falls, his top lip slits apart. The skin of his face is smooth, like a child’s. I am always surprised by how much younger his face looks than it is – it wrinkles only when he laughs, those surges of laughter he gets sometimes. There have been a few on this holiday when there hadn’t been any in a while, loud and violent when I least expect them, and when they come they scare me, those wrinkles that open like wounds, the fear that I will disappear inside them. They leave me to wonder how this can be the same man that I love, how there can be nothing else he is hiding.

I can’t imagine him any differently. I met him when the wrinkles were already there, perhaps a little less deep. At work, he would meander past my desk. He would ask: what are you doing this weekend, what are you doing tonight. This was before we started fucking, and the lovely edge of his nose would upturn slightly between fresh and transitory eyes.

I would always reply that I was busy, going to a music event, or brunch, or the opening of a restaurant. Sometimes it was true, sometimes it wasn’t. In my early twenties, there were times I went out and times I stayed home and waxed my pussy raw and drank vodka with a slice of lime drowning in ice. I liked being alone, I could watch junk TV and dance to the Scissor Sisters and later I would smoke in bed while I waited for his messages to light up my phone. But I never told him that. I wanted him to think I was always busy. I was convinced it would turn me into something to desire.

Now, I no longer lie to him about what I do. Instead, I lie to myself, when I tell myself it does not matter.

*

At the beach, the water is smoky-blue. It slimes with chalk where the sandbank melts to sea. A few kicks out and it turns iridescent, so clear that it blinds against the white sunlight, the cliffs, the blue spirals of trees. Somewhere behind, the sky vibrates with the screech of cicadas.

We call this our beach. It was empty when we discovered it, on the second day of our holiday. We’d grown bored of the chlorine stench of the pool, the pop songs from the hotel bar, the sunburnt British tourists ordering too many drinks. Like we were any different. We’d walked the dust road along the coast instead, our backs turned to the incongruous monstrosity that was our hotel. The shore was quiet, the cove steep to get to, the beach just wide enough for our towels. It was empty then and has been empty since, every day we’ve come back to it. I like to think no one knows our beach but us: we are pioneers, the first to break its seal.

Our beach. I tread deeper. The water ripples his shoulders as I swim away from him. The short hairs by his ears curled dark. I gurgle through my mouth, like a shark. Salt burns the back of my throat, cracks my lips as I raise my face to the sun.

“Tell me a secret,” I’d asked him the very first time we’d gone out together. An underground bar, the purpuric lights, each drink worth more than an hour of my work. His fingers were bare of rings and already welding to mine. He’d inched closer. “A secret?” he’d asked. “I can’t swim.” And then he’d laughed, the eruption of wrinkles from the corners of his eyes.

I crawl back to him now, to the sandbank. I grab the soft flesh at his sides. I think of his daughter’s swimming races he never misses, of his feet anchored safely into shifting ground.

“Have you ever,” I ask, the words falling out of me, “had sex in the sea?”

He hesitates. “Only with my wife,” he says eventually.

He pulls slowly at the bikini string behind my neck. I feel the knot come apart, the exposure of triangles, the excitement between my thighs. I hate myself. I wish it didn’t have to be this way and that I wasn’t grateful that it was.

*

We were meant to go away last summer. Then his wife got sick, and he cancelled the holiday.

“It’s not a good time,” he told me. We were sat in a café at the end of his street, the results from the biopsy not back yet but the doctors had already announced that the scan didn’t look good. He was scooping his fingers through his hair like he does when he’s anxious, pulling hard. I worried he would yank out some silvery bristles so I reached forward, held his hand across the table. “We shouldn’t go until it’s dealt with,” he said. “I’m sorry.”

I turned my face away and said nothing more. I didn’t want him to see me cry. It wasn’t about the holiday, it wasn’t even about him. It was about me, and the fear that I would lose everything.

*

Heat burns through the visors of our caps. We are fuchsia between the UV and terry-blue towels. I splurge lotion onto my hand. He turns over, I know there are layers he wants lathered on his back. He is paler than me, he will burn to blister. When I’m done, he traps my fingers, kisses each one. “Tastes lovely,” he says, and almost by accident I smile.

Later, I feel him leave my side. My eyes are closed, I don’t watch him go. The heat turns every movement to effort, the screech of cicadas becomes a cry before he returns with a four-pack of beers and a box of cherries. We eat the cherries unwashed, spit the pips back into the plastic. The beer tastes of lukewarm blood.

He asks: “Who do you love more, me or your husband?”

The question slides onto me like butter in the unbearable heat. I think of the year he’s spent with his wife in the post-op rooms, the chemotherapy suite, the injections at home and the children passed around between friends for a room to sleep in. The days of annual leave taken for her whether he wanted or not, he did not get a say nor did he try to, he simply spilt into that space between husband and carer while she became an illness and no longer something to desire, perhaps never to be again. As the year went on, I wondered whether things would ever return to how they were before, whether that thirst for each other would hang on or if it would just be easier to let go.

I squirm, now, in the heat. Even the gold band on my finger has softened in the sun. I pick a cherry’s flesh from my mouth. I watch him, the can’s metal lip cutting through the spikes of his beard.

He’s forgotten to shave. That’s how I know that he, at least, is at peace.

*

“Are you happy?” I’d asked him once, not long before his wife’s illness. It must’ve already been brewing inside her as he fell asleep with his back to her every night, the occasional laugh about something the kids had done in school and not much else. His work was taking up more time but they needed the money for the school fees, the nanny, the groceries, and then there was inflation and a mortgage to pay, the after-school clubs and the football summer camp they’d be sending their little boy to in the summer. His wife looked more anaemic each day, the iron-blue tinge in her undereyes and the general weariness of her appearance, although he did not look at her enough to notice, nor did she herself.

“Is anyone really happy?” he’d asked in return. “That’s a philosophical question.” And he’d picked up his phone and started typing out emails as if that settled the matter.

But it didn’t. I laid there thinking of his wife who’d chosen a man who would never be satisfied, and whether all men were like this, and all of humankind; whether she too detested that their love had grown old, whether it was natural to want to replace the old and broken for the something unknown.

*

“Look,” I call, pointing at the shoreline. “Isn’t that our beach?”

We’re at the back of a hired jetboat. He’s wanted to do this from the beginning: ferry out until land flattens to greens and blues; watch me dive into clear water; pretend it is possible to get away from everything, family and money and even the judgement of people on shore. The wind yanks my hair back, fills his mouth with it. He laughs, and I see the wrinkles, and I want to bury myself inside them. I follow the light behind him that skitters off of waves until the duskiness of shore, the cliffline reaching upwards to the sky. From that cliff, I see black dots coming down, gettinng bigger. It can’t be but it is.

“Look,” I shout. Towels stretching onto sand, a parasol pops open. The dots run into the water. “There’s people on our beach.” My voice is petulant above the boat engine. “It’s ruined.”

“Stop,” he says.

“It’s ruined. It’s not our beach anymore.”

“Stop the boat,” he calls louder, to the skipper. Then he leans into me. There is only a lapping of waves, our beach filled with strangers’ cries. He whispers, “Just because it’s different from what we thought, it’s not ruined.” And he folds his cheek into mine. That rasped beard. The old pink skin, and all the freckles that come on through.

*

“Our last supper,” he announces to the man in the lobby, the man at reception, the waiter who delivers vodka tonics to the table. I grab the glass by the stem, the skin of my hand smooth and gold, my hair grazing the space where shoulder and dress meet. It is the backless dress again. I bought it a long time before we met, for many years I could not fit into it but now I’m glad I can.

The drink dulls my throat. We always get vodka tonics, since that night in the underground bar all those years ago. “Two of whatever the lady wants,” he’d ordered without taking his eyes off of me, and upon hearing my request he’d grimaced. “Is vodka tonics really what young people drink these days?”

He was in his thirties then, almost ten years older than me. We were both healthy. At the time, he felt superhuman: his age, his wisdom, the carelessness for his money and his uncontrollable laugh. “You know what,” he’d said at the end of the night, tipping back the last of his drink, the fourth or fifth, I had lost count by then. “I could get used to these.”

“Cheers,” he says now, raising the glass. He’s shaved his beard in preparation for tomorrow. In his mind, he is already home. “We had a lovely holiday, didn’t we.”

“Lovely,” I say.

“Back to the wife.” He winks. “I’d rather stay here with you.”

And there it is again, the smell of chlorex and must, of compromise and loss.

“I’m sorry,” I say.

“I am too.”

“I’m sorry it’s come to this.”

“Wait,” he says, but I don’t, I can’t. It’s been waiting inside me longer than I can admit.

“I’m sorry you can only sleep with her by pretending she’s somebody else,” I say. “I’m sorry you have to drink to blackout to convince yourself you still love her.”

“That’s not true,” he says.

His eyes bore into me and mine into the waiter’s hands as comes to remove our cocktail glasses. They’re half-full but I let him take them anyway. Another waiter uncorks the wine. I take a long sip of it, piss-yellow, citrus and liquorice, a soured sweetness. I remember being young when I was convinced I was already old, the Scissor Sisters and the bedsheets that smelt of smoke, the vodka with dashes of lime that tasted like I was running towards something rather than away from it.

My dress sags low across my amputated chest. I fiddle with the straps. I turn my head so he won’t see me cry.

“Pretending to be other people,” he says. “So we can save this, so we can save each other.” He reaches for my hand before I can move it, his fingers around mine, our gold bands hardening to each other. Then he leans back, cracks his face to wrinkles, a humongous laugh. “Isn’t that love?”

____

Francesca Carra is a London-based writer. She has published or forthcoming fiction in Flash Fiction Magazine, Tamarind and the Skeins anthology by Linen Press.