‘Selling England by the Pound’: A.C. Bevan finds a way to halt the slide

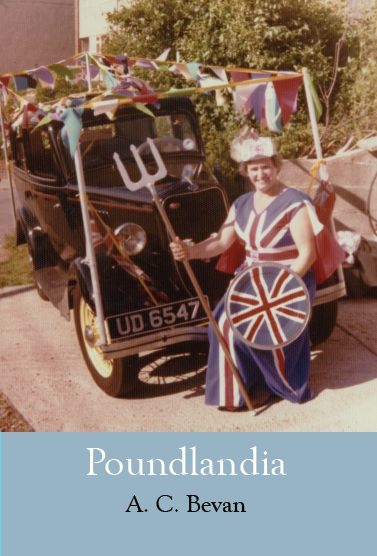

A.C. Bevan | Poundlandia| Mica Press: £10

Reviewed by Andrew McCulloch

A.C. Bevan has found the perfect title for his well-plotted and immensely readable first collection – a critical, compassionate look at a cut-price world of unconvincing simulations and cheap substitutes, epic only in how far it has fallen. One of its voices is that of the provincial ‘little Englander’ looking for refuge in a more knowable past – ‘some statute acre of an English field/that is for ever Poundland’ – although the deeper malaise is late capitalism and its cultural consequences. But it is also a protest about the fact that language has become as worthless as everything else. Part of Bevan’s purpose, here, is to find a register that will restore meaning and value to a world from which they seem in danger of disappearing.

In ‘Lego Land’, for example, real places shrink to a table-top layout where objects dissolve into their own plastic shadows. The country has become a playpen, its inhabitants infantilised, pushed around ‘the isles of Toys ’R’ Us’. People live in ‘Duplo starter duplexes’, visit a ‘Pleistocene model of Stonehenge’ and spend money generated by ‘pop-up & startup’ (‘Anti-Monopoly’). The past only dramatizes the sickness of the present. ‘Bill of Mortality’ presents the pathology of our own times in the language of the eighteenth century and reveals disturbing new threats: ‘Drown’d in the Kentiʃh Channel . . . Found ʃtabbed in the Wrong Poʃtcode . . . Trold on ʃocial Media’. In ‘Saturnian’, the litter of orbiting space-junk on which we rely for GPS and satellite TV is evoked in a verbal pile-up that throws the title’s other meaning – the Golden Age of the god Saturn – into darkly ironic relief. Here, heaven is being able to ‘watch your free-to-air TV, or geoparse/your personal coordinates as you navigate your car/round the loop roads & orbitals’. The gravitational pull of the poem’s 14 lines manages to stop things falling apart completely: the centre holds, if only just. Elsewhere language appears less safe: ‘The AI Romantics no longer die young. In/fact, with their cognitive neural networks/context-free seed phrases & source texts/gradient descents of linear regression. . . they don’t die at all’ (‘The Practice of Writing’). Beneath the jokiness of ‘a tweet to a nightingale’ lies a serious concern that bot, app and predictive text might destroy the ability – even the will – to wrestle with words until they actually mean something.

The second section, ‘Terra Sancta’, is a dialogue between a latter-day Galahad and two ‘hooded brothers’. The quaint Englishness of one and the truculent nationalism of the others are equally self-parodic – a cardboard Quixote in search of lost Albion and a couple of ‘Sun & Mail’ readers prophesying war – but the antagonisms they illustrate are real enough and in the final section – ‘Sub Urbia Rediviva’ (‘Under the Recycled City’) – Bevan looks for what common ground he can between them and us, then and now: ‘Neolithic’ conflates modern brutalist architecture and ancient stone circles – ‘A lithic machine/for living in’ – while ‘The Foragers’ maps modern urban poverty onto ‘A preagricultural society/connecting with its food source/in the wastes behind the Co-Op’. Connections emerge, too, between poems: ‘Eclogue the Last’, a seventeenth century shepherd’s request for a woollen shroud, anticipates the final poem, ‘Allotment’, where the speaker asks to be allowed to ‘run to seed . . . in the midst of must & matter, mould/& litter.’

By the end of this collection, Bevan has earned a right to the language of Domesday – ‘As Fyftyeth Moste Elygyble/Bachelore I holde this/demesne as he afore me’ – and the Exeter Riddle Book – ‘we are risen from creation/myth & mystery religion//in weather lore & cycle of/the grain we are born again’. Smart connectivity is clearly no more than an instrument of capital and control. The algorithm ‘crashes your financial systems/hacks your referendums’. The only way to get safely beyond the virtual, it seems, is to put down roots into real earth.

Reviewed by Andrew McCulloch