Fantastical, genre-defying psychedelia delivered in exuberant prose

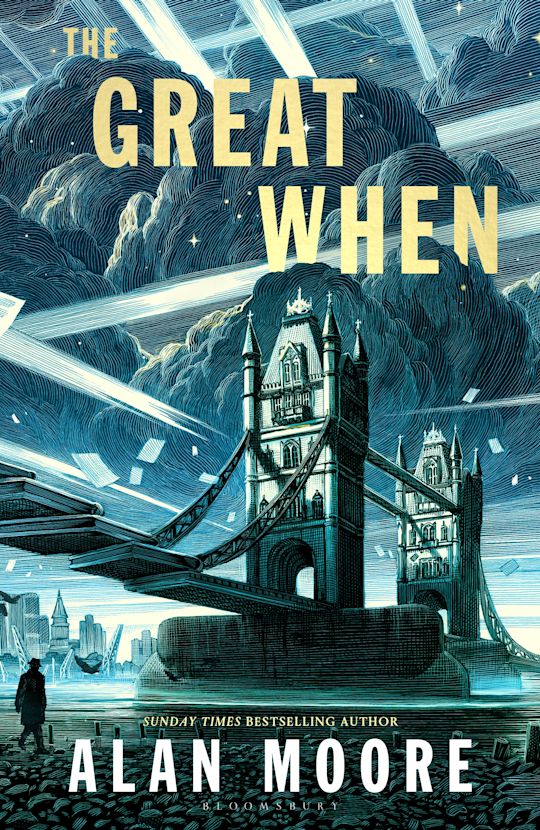

Alan Moore | The Great When: A Long London Novel | Bloomsbury: £14

Reviewed by Sam Lamplugh

What is genre? For Alan Moore, ‘widely regarded as the best and most influential writer in the history of comics’ if dust-jacket biographies are to be believed, the answer to this question is almost certainly “Who cares?” For a reader of The Great When, the first in a slated series of five novels set in ‘Long London’, the question lingers in the margins, the book’s playfulness and straddling of different forms inviting us to grapple with art and imagination in all their multifaceted variety.

We first encounter Dennis Knuckleyard, the improbably named protagonist of Moore’s novel, at nine years old, in 1940. Hemmed in by the Blitz whilst stealing cash from gas meters, Dennis witnesses a gate open to another world amongst explosions rendered in onomatopoeic BOOMBOOMBOOMs. Out steps Shakespeare, or a version of him, who stares horrified into the flames and in doing so focusses the perception of our hero on the enormity of his experience, the artist’s gift for clarifying reality embodied. The Bard has emerged from ‘Long London’, a realm which sits behind and beyond the ‘Short’ version experienced by its mundane residents, a realm where archetypes and concepts merge and flow freely in a timeless nexus of streets mirroring those on the mortal plane. Nine years later, amongst post-war detritus and encroaching post-modernity, the eighteen-year-old Dennis finds a book which comes from this fantastical realm and embarks on a quest to return it.

The themes and motifs of The Great When will be familiar to those who have read Moore’s previous novels, 1996’s Voice of the Fire and his magnum opus, 2016’s Jerusalem. Both works orbit a similar contrast between the seemingly linear substrate of lived experience and an eternal realm which lies beyond, examining the interactions and effects these have on each other to interrogate aspects of contemporary life, most notably the apparently impassable late capitalist ideology in which we swim (or, perhaps, flounder). Where these previous novels focussed on Moore’s native Northampton, however, and culminated in the present, the move to London and a post-war frame modulates his approach. Here, Moore’s style—characterised by lengthy descriptive passages, with few nouns unmodified by adjectives—seems not as documentarian as before. Instead the prose is dreamlike, and frequently nostalgic.

By setting the novel in a time before his birth and a location beyond his immediate experience, Moore is comfortable to indulge in caricature more so than he has previously. Knuckleyard is something of a dolt, often being told what to do by those around him, or having the same information explained to him repeatedly. His landlady, Coffin Ada, is an emphysemic chain-smoker, whose every line is populated by coughs and curses. Early on, he meets a sex worker with a heart of gold, who both rescues him and must be rescued in turn. The reader’s mileage with these characters may vary. The novel is built around a series of recursive loops, walking tours of Shoreditch and Spitalfields, where the same streets pass by on a zoetrope. It may be too slow for those who enjoy traditional, plot-focussed fantasy, and too occupied with fantastical imagery for those who enjoy Psychogeographic literary fiction in the Iain Sinclair mould (a writer to whom the book is dedicated).

The reader who persists, however, will find in The Great When a fascinating experiment in form, theme and genre. While the London of 1949 is rendered in a third-person, past tense, closely-focalised mode, Dennis’ trips to Long London snap the prose into italicised present tense, replete with inventive and startling detail, encountering ‘bottle caps with brewery insignias and spider legs of silvered cork’; ‘a tremendous sphinx, high as St Paul’s and hewn from limestone, with its body a war pachyderm that wears a castellated howdah on its back’; and ‘Blake, Bunyan and Defoe perched on headstones in fluorescent conference’. These passages are frequently funny, often horrifying, and never boring. The seriousness with which Moore treats the fantasy sections allow the caricature and microcosmic observation of his mundane world to shine, and vice-versa.

In the rubble of post-blitz London, it seems to be only art which can rebuild the world—all art, and all imagination. The Great When is a fine work of fantasy, shot through with a humourist’s party bag of one-liners, a horror writer’s eye for imagery and high literature’s desire to challenge readers and confront the shibboleths of the contemporary world. What is genre? It’s hard to reach the end of Moore’s novel and provide any answer other than: Who cares?

Reviewed by Sam Lamplugh