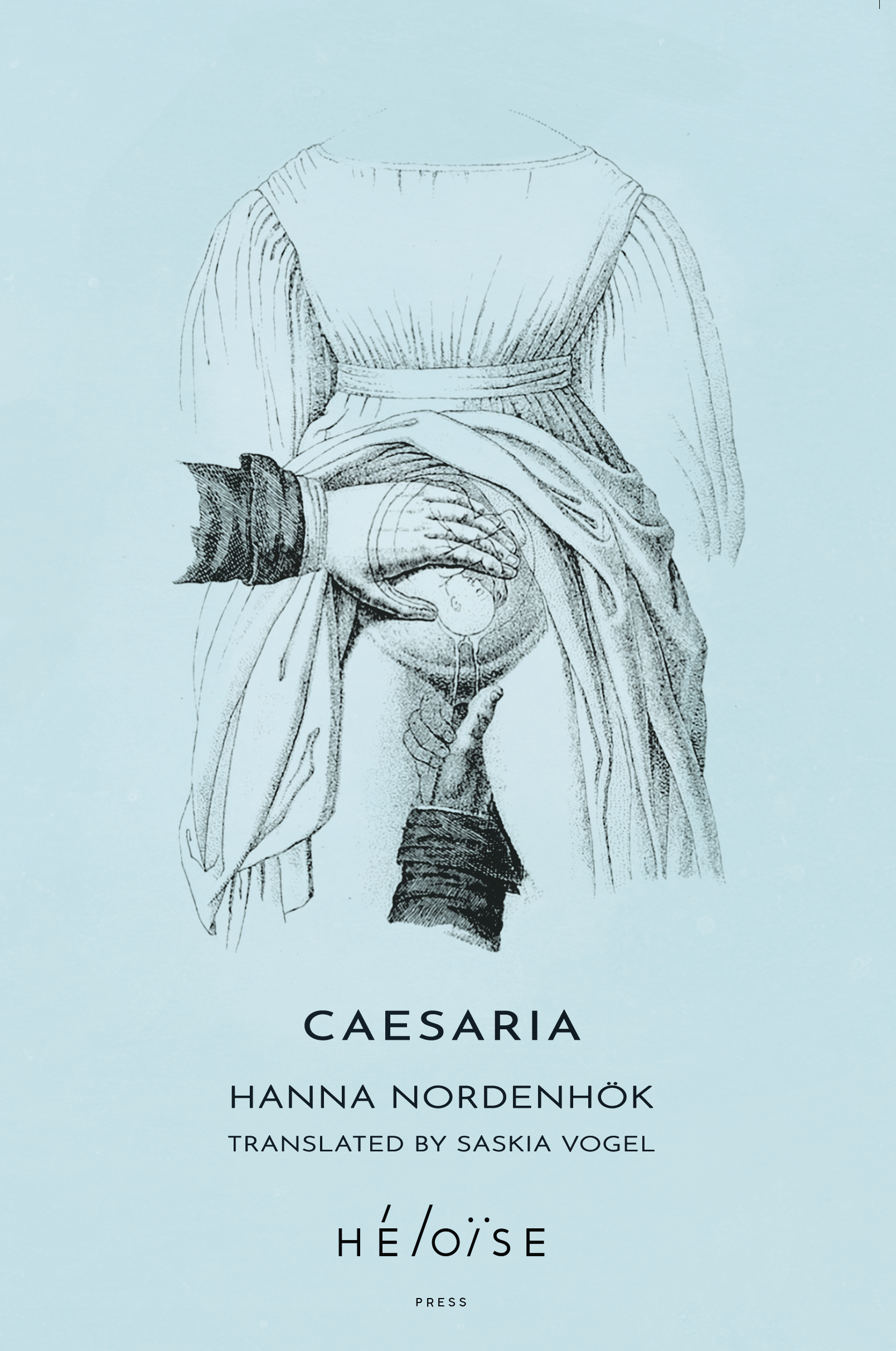

The beautiful and grotesque Gothic tale of a young girl’s subjectivity under the medicalizing male gaze

Hanna Nordenhök (trans. Saskia Vogel) | Caesaria | Héloïse Press: £10.95

Reviewed by Daniel Pope

In 19th-century Sweden, Caesaria, the first child born successfully from a c-section performed by Doctor Eldh, is kept in a mansion in the countryside as a kind of living trophy. On his occasional visits, Doctor Eldh repeats the same ‘Creation story,’ the story of the birth that killed her mother. He often asks her to transcribe his dictations about gynecology: ‘Thus, the fortunate surgeon himself becomes the author of the human delivery per excellentiam, hitherto reserved for woman.’ Doctor Eldh keeps the malformed pelvis of Caesaria’s mother, which he frequently takes out to show her as he reads from his medical papers:

Albeit the uterus, since time immemorial, has been regarded as the source of various dark forms of disease […], the organ as such remains a mystery in many respects. Its influence on the rest of the organism and its pathological changes to some extent persist in defying the shrewdest investigations

When the doctor goes back to the city, where he lives with his two biological daughters, Caesaria yearns for the attention of her Creator, left in the care of Fanny and the mansion’s changing ensemble of caretakers. Kept in this constant state of waiting and wanting, and with nobody around her curious about her thoughts or feelings, the internal richness of Casearia’s subjectivity is projected outward. The prose’s lilting, hypnotic rhythm gives an impression of the unceasing repetition of Caesaria’s life, which is reinforced by the novel’s elliptical narration. This keeps the drama at a foggy distance that makes it feel mythical, but the prose style renders the mansion, the landscape, the animals, and the whole of her hermetic world with breathtaking sensuous precision. Between shimmering paragraphs of narration and description come sentence fragments that make the objects suddenly pierce the reader’s eye with a startling exactness: ‘The yellow half-light of winter days. The splayed black fingers of the trees.’

With the doctor gone, time seems to stop, and everything drifts in the slipstream of the dreamlike narration; but, as always, time must assert itself again. Having received her education on womanhood through the violent, scientific terms of the medicalizing male gaze, Caesaria binds her budding breasts, which she calls ‘boils,’ in an attempt to arrest ‘her morbid disposition,’ the puberty that will turn her into a woman—into the thing that the doctor seems to despise above all: ‘thus,’ says one of Doctor Eldh’s medical papers, ‘the woman embodies an organism that is ever attacking itself.’ As she ages, Doctor Eldh seems to lose interest; he comes less frequently and stops bringing her the toys and sweets that she requests, which occasions a protracted panic that manifests in a series of apocalyptic hallucinations.

For much of the novel, the setting and farm animals dramatize the increasing violence that underpins the scientific appropriation of life and reproduction, but the true focusing agent of the novel’s themes is Master Valdemar, a young, wild-eyed man who may be a brilliant composer or may just be insane. Doctor Eldh, who meets Valdemar in his high-society circle, installs the man in the mansion so he can recover from an obscure psychic illness. Even when it becomes clear that Valdemar has begun to violate the routine calm of doctor Eldh’s Eden, the doctor continues to hold him in high esteem. They are two sides of the same coin: Valdemar enacts the irrational violence that simmers beneath the ‘objective’ male scientific gaze, which sees women’s bodies as unexplored landscapes to be mapped and dominated.

It takes some time before the arrival of this antagonist, but Nordenhök’s brilliant foreshadowing and the growing sense of tension and unease that saturates the setting do more than enough to keep a reader going. Indeed, the pleasure of reading this novel is due in large part to the way that Nordenhök uses the scalpel of Caesaria’s gaze to carve out psychic space in a world where she has been marginalized.

Reviewed by Daniel Pope