The novel is always dying, never dead. Prophets of doom are readily available. Will Self would have you believe that the ‘analogue brain’ is going extinct. People just don’t read anymore, we hear. Even students who are paying for a reading-and writing-based education don’t read the texts they’re set to read. (Perhaps that last bit is true, but it was also largely true twenty years ago when I was an undergraduate.)

If we live in an age of ‘content’, and if such content is theoretically formless (or at least form-agnostic) then reading a physical book as opposed to listening to it or skimming it on an e-reader would seem to be largely a matter of convenience. And yet, after a pandemic-related high watermark in 2020, sales of eBooks have fallen away again as a percentage of total book sales. Readers are still in love with the book-as-object, it seems. I know I am.

Since our brains are analogue and so are books, the bookmark keeps a time-honoured place in this object-relationship. A bookmark is an important, functional tool, but it can also become a loved, sometimes ornate object in its own right. The reader-bookmark relationship is at the core of Joe Devlin’s exhibition at the Portico Library, ‘A collection of modified bookmarks’.

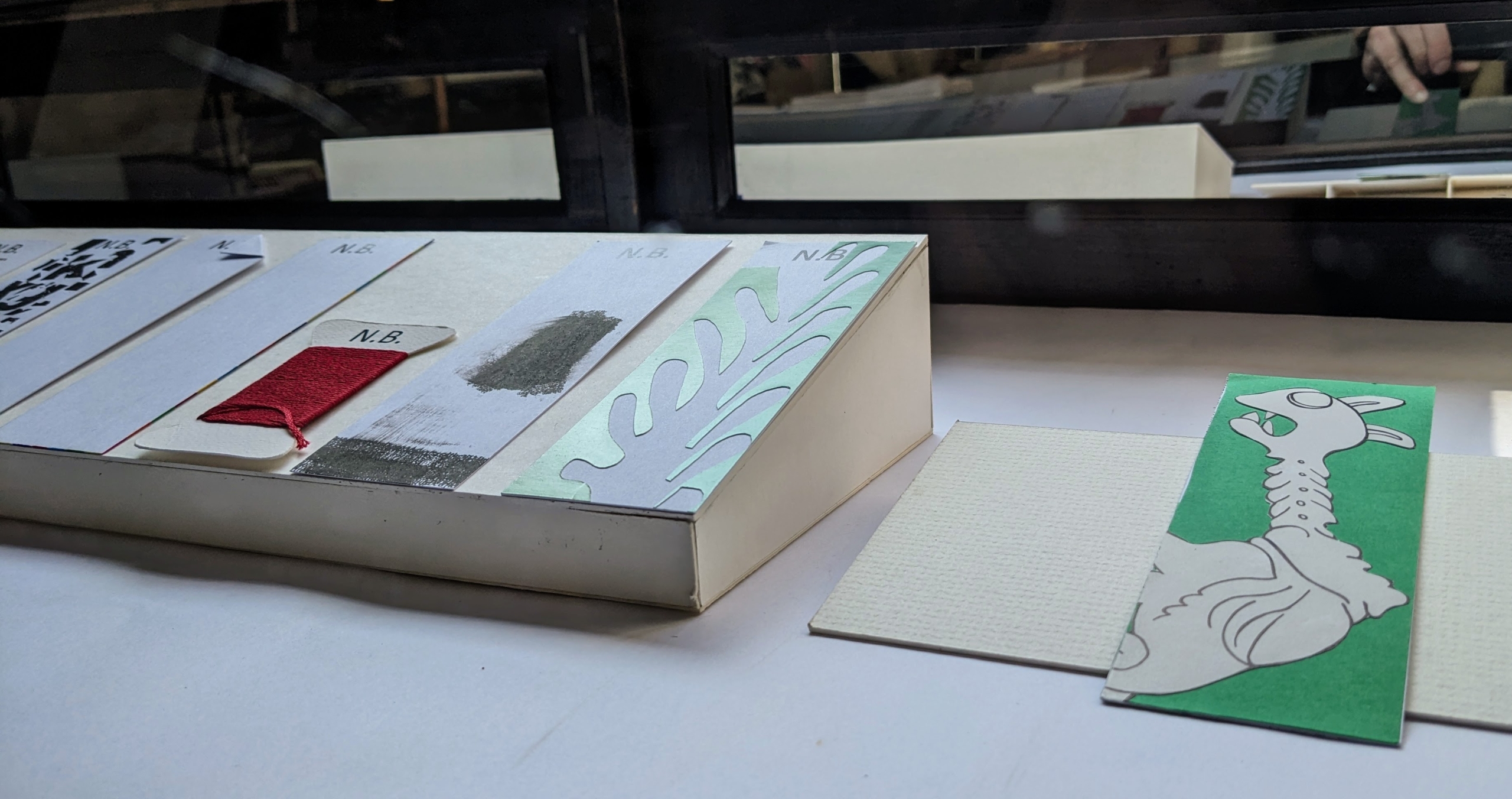

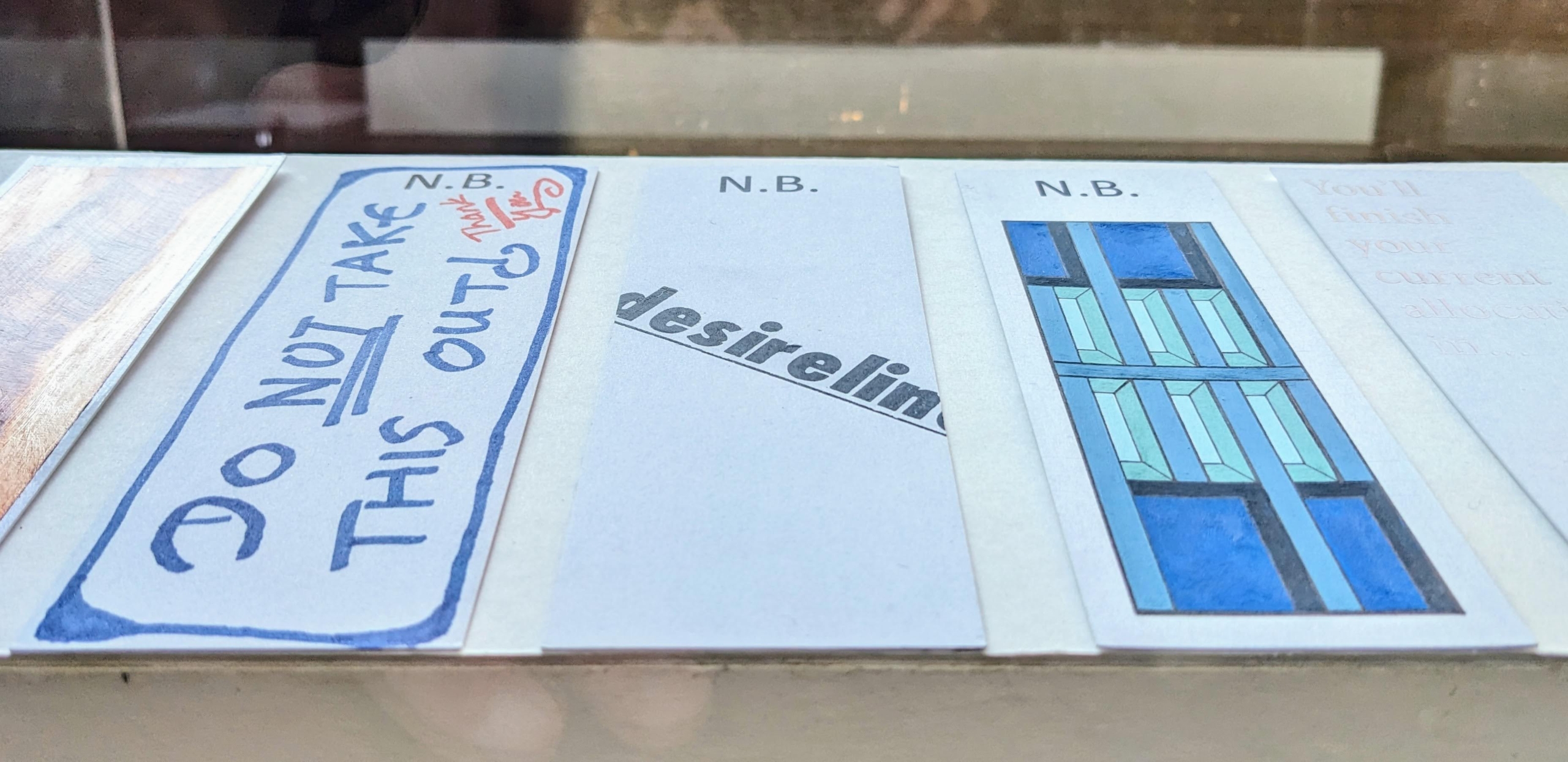

22 artist-modified bookmarks are laid out like jewellery in two glass cases along the sills of the library’s tall south-facing windows. A bookmark by Ed Hadfield lies in an open book. The bookmark’s two-dimensional face is dotted with a series of white, braille-like raised patterns, applied like tiny waves of stucco, perhaps hiding the erased names of other owners.

Many of the bookmarks have been transformed into compelling small artworks in their own right. Brian Mountford’s contribution features a grimacing creature against a field of green, a gargoyle to guard any book into which it is inserted. Gregory Betts produces a Rothko-esque piece of abstract expressionism in monochrome ink, while Noel Clueit’s organic form evokes Matisse’s cutouts. Louise Giovanelli’s bookmark becomes canvas for a swirling, painterly piece, and Matthew Houlding sets a graphic, Brutalist illustration within the rectangular white space of the cardboard.

Pavel Buchler’s bookmark plays with form, one corner folded down like a page. Claudia de la Torre and Maeve Rendle’s pieces look to play active roles in reading and/or writing. The former carries a list of pleasingly obscure words such as ‘permeabilizing’, while the latter is covered with a pencil-written draft of what reads like a book review.

Other bookmarks are utterly transformed. Michael Hampton’s second contribution features a black and white photograph blending two figures, a stylish woman and a man in uniform with medals on his chest. Below this photograph is a piece of cardboard dotted with frayed holes, perhaps used once to mount the medals in the photograph, or punched through by bullets. David Bellingham’s two bookmarks are cut away in geometric bites, as if they are being methodically devoured as the book is being read.

Joe Devlin, the mind behind the exhibition, heads Nuts and Bolts, an independent publisher whose productions emphasise the materiality of the printed word. Looking at these bookmarks under a high Georgian dome in the reverent, hushed peace of the Portico Library elevated these small statements of book-materiality. With sunlight coming through high panels of stained glass, reflecting off the touch-smoothed leather spines of books lining the walls, it occurred to me that if the book-as-object ever does die there are plenty of us to ensure it will get a decent burial.

At The Portico Library until October 5, 2024.