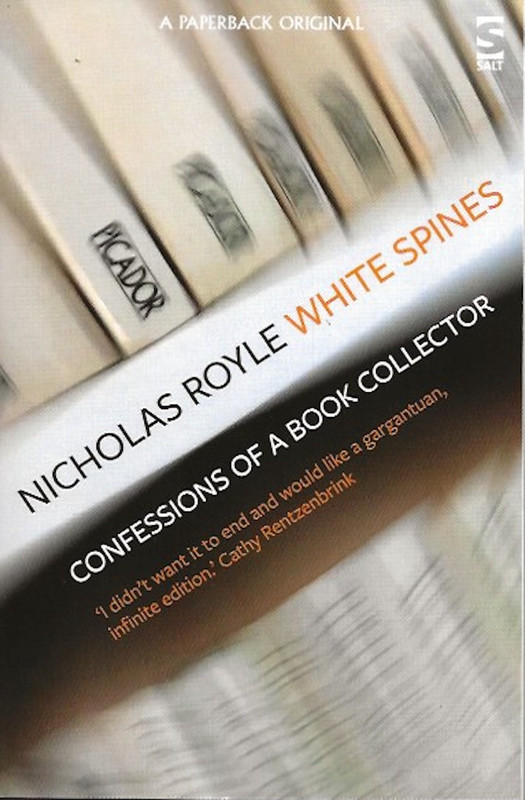

Nicholas Royle, White Spines, Confessions of a Book Collector, Salt Publishing; £9.99

What I anticipated, on hearing about this book, was something similar to Francis Spufford’s The Child that Books Built, a kind of bildungsroman about the psychology of reading. I was wrong. This unusual volume is more of a literary travelogue for readers, writers, and book lovers of all kinds. It takes the reader on a journey around the UK, via second-hand book shops, some of which are already known to the author, and some of which are encountered along the way. It is a quest, for original editions of Picadors with, as the title suggests, white spines.

The journey is an investigative one; an exploration of the life of second-hand books and the people who have owned them, as revealed in the glimpses provided by inscriptions (‘Anne, a book about desolation is probably not what you need right now…(but) How was I to know?) and inclusions (business cards, photos, receipts, a body shop card, a love letter and even an envelope containing a cheque). It includes an appraisal of the relative merits of book covers and fonts (if we are not meant to judge a book by the cover, the author queries, then why do publishers pay so much attention to them?) a consideration of the lives of the writers, (many of whom the writer has encountered in the course of his considerable career as writer, editor and journalist), and of the people who read them. It is also a consideration of the people who own second hand book shops and the people who visit them, offered to us in snapshots and snatches of conversation.

Second hand bookshops are distinctive in many ways. In them, (as indeed on the list of Picador titles), forgotten or overlooked authors are placed side by side with more famous ones, such as Ian McEwen or J G Ballard. There are no paid-for displays, or ranking according to sales. These bookshops are committed to the enduring life of a book rather than to its immediate exchange value. Prices seem largely to be determined by the whim of the proprietor rather than any negotiation with marketing departments, publication or distribution costs, sales estimates or Amazon. Many of the books have an individual value quite separate from market sectors and profit sheets. All of them have been owned, many of them loved. They may be bought on a whim or by a dedicated collector who has been looking for a particular title for some time. The circumstances that have caused them to find their way to this or that second-hand bookshop are as varied as the titles themselves. In a sense, the existence of second-hand bookshops is a kind of metatextual comment on the publishing industry, offering an alternative set of values, and suggesting multiple stories related to the original product. The second hand bookshop exists, therefore at a kind of tangent to the rest of the book industry, most of which is focused on immediate profit. This, in itself has a certain charm.

White Spines offers glimpses into this miscellaneous and multi-faceted world, as well as a quest for a particular Picador brand, and sketches of the people behind both; the editors, illustrators, writers, book-shop owners and readers. It is entertaining, erudite and witty. It provokes many questions about the essential value of books. It certainly caused me to reflect on my own reading habits and preferences and led to one question in particular that has previously arisen in my mind, and which I usually ignore, because I don’t have an answer to it:

What does it mean, in this age of multifarious publications and publishing media, to be ‘well read’?

Not that long ago, when I started university, perhaps, I thought I knew the answer to this question. It involved having read certain classics, enough foreign authors to augment my English Literature-based education, some contemporary writers who were held in high enough esteem to have made the Booker shortlist, and a small selection of non-fiction.

By the time I finished university, however, this view had almost entirely disintegrated; the canon had been comprehensively dismantled and I was newly-equipped with a knowledge of post-colonial and working class writing. Also with an awareness that there were many, many more books appearing in the world by the minute, than I would ever get to read.

On the evidence of this book, Nicholas Royle appears to be well-read. His reading is eclectic, though coloured by a certain taste for the Gothic thriller, (Siri Hustvedt, Susanna Moore), the nouveau roman, (Alain Robbe Grillet, et al.). Since, as he says, every book contains a world, he is very well-travelled indeed. As I read White Spines, however, I came to see the impoverished state of my own reading.

Royle says, for instance, that his favourite writer of all time is Derek Marlowe.

Derek Marlowe!

I had never heard of Derek Marlowe before picking up this book. I would not like to hazard a guess at the type of books he has written (avant-garde thrillers with a gothic touch, perhaps?).

I suppose that at one time I must have aspired to be well-read. In childhood, I quickly read my way through all the books available in the children’s section of my local library and had to be cautioned against taking adult books out by a kindly but firm librarian who thought The Alexandria Quartet was too sophisticated for a ten-year-old (she was right). I suppose I thought I was well-read, until I read this book. My reading averages at about 70 books a year (fiction and non, some poetry) plus all the work sent to me by students. However, this book definitely made me realise I have some catching up to do. I have never read Alain Robbe-Grillet, for instance or Marguerite Duras!

Furthermore, when Royle mentions writers I revere, such as Virginia Woolf and Balzac, it is clear that they are not his favourite writers at all.

Does this matter?

Surely it is part of the infinitely complex pleasure of reading and literature in general, that its value is, to some extent, personal? And that there are always more journeys to go on, more paths to follow. And, above all, that it allows us to make deeply personal connections both to writers and to other readers.

White Spines is essentially a book about connections. On the last page Royle writes:

“I often wonder when I’m walking down the street reading whatever I’m reading…how many other people in the world are walking down the street right now reading the same book…I feel a sort of connection with them. And that’s why I think stories are important…”

The stories in this book are often very funny, sometimes poignant, or tragic, commemorative of the lives of people who have loved books and writing, or reading. It is not really a guide to Picadors, or to second hand bookshops or authors or how to become a book collector. It is essentially a love story, a voyage d’amour in which the love is both intimate and outgoing, accessible and obscure.

by Livi Michael