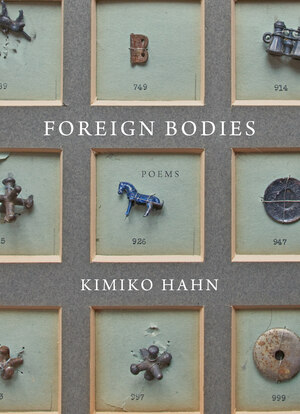

Kimiko Hahn | Foreign Bodies | W.W.Norton: $26.95.

There is a strong, driving sense of personal narrative in the poems in Kimiko Hahn’s tenth collection, Foreign Bodies. It feels clear that the ‘I’ in the poems is the writer, herself. This is a first person who is almost fiercely committed to the narratives that create the trajectories of the poems in this book. The poems are often quite substantial sequences running over a number of pages. And there is another sequence ‘charms’ which also runs through the book. Thus the reader is often taken through a number of stages in Hahn’s poems.

Those stages may be occasioned by and likened to the ‘foreign bodies’, the objects, that the cover blurb points out. Thus, the stages of the narrative vehemence are sometimes pegged to objects. The first poem/sequence in the book, is called ‘Object Lessons-From Chevalier Quixote Jackson’. It meditates on the ‘foreign bodies’ which where taken from actual bodies by the Dr Chevalier Jackson. The cover shows a section from a panel of these foreign bodies, that resides in the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. These objects are as bizarre as you might imagine, ‘miniature binoculars, silver horse-charm, four open safety pins’. Hahn’s poem then meditates on the objects that she had accumulated herself. In a visit to a safety deposit box, she notes, ‘old wedding bands, diamond earrings twice worn, and Mother’s jewelry-inherited and rarely worn. No-never worn. Safe keep. Kept here. From myself.

Then there are bonds for the children. (I haven’t ever checked the other one containing the deed with the new husband.)

This extract will give you some idea of the tone and cadence of Hahn’s poems. The poems are often clear and unvarnished, often conversational. The reader is not so much let in into Hahn’s musings as taken by the hand through them. At the end of that first paragraph, the staccato, broken syntax is as much conversational and emphatic as it is a tautening of the ‘poetic’ line. The reader is left in no mind as to the attitudes here, and also the relationships of which the words are clearly the tip of an iceberg. And in the next paragraph (this is an extract from a ‘prose’ section in the poem), there is a neat irony with the word ‘bonds’. And that only superficially throw-away sentence in parentheses. There’s a kind of conversational exoticism too, in the play with grammar, ‘Safe keep’ and ‘the new husband.’ Here too, Hahn’s skill is to point the reader to much larger matters, in the way that a good novelist would, without actually stating things.

There is much more ‘exoticism’ to this poem, too. Particularly, in Hahn’s almost delight in the weird collection of substances and objects that humans put inside their various orifices; the mouth being only one!

Towards the end of this collection, Hahn appends an essay on ‘Japanese poetics.’ Hahn comments that ‘in a haiku, one word can explode the seventeen-syllable economy.’ Hahn is fond of using the word ‘explode’ about the potential of words. Towards the beginning of the essay, she suggests that ‘Words can be as unstable as nitroglycerin.’ And Hahn is much taken by ambiguity; part of her essay discusses ‘pivot-words’ where ‘a series of sounds is used to mean two things at one by different parsings.’ She goes on to show that a single word in a poem by Ono no Komachi means both ‘moon’ and ‘chance’. She then goes on to show how four different translators have been unable to reproduce the ‘potential explosion’ enabled by the ‘pivot word’; an effect which is irreproducible in English. In effect, the force of the poem as a whole is lost in translation.

Famously, of course, Frost said that poetry is what gets lost in translation. Hahn’s essay emphasises this point. However, her point might have been better concentrating the nature of ‘pun’ with which she begins the essay. As she comments, her own poetry is often an attempt to breath new life into puns. And ambiguity both can be and has been built into poetry in English since time immemorial, as Empson also famously dissected. Hahn, herself, acknowledges this in the punning on ‘object lesson’, ‘foreign object’, ‘constant objection’, ‘direct object’, and ‘object theory.’ A colleague of mine once appended ‘round objects’ in the margin of a report, to which his line manager replied with ‘Who is Round and why does he object?’ Sometimes puns can be lost, but a poem is usually a place to look for them.

And that wrought density of writing isn’t what the reader might look for in Hahn’s poems. What emerges from these poems is a powerful empathy for humans but also for animals. In ‘Hatchlings’, Hahn writes about the ‘cooing’ that researchers have found crocodile hatchlings that emit just before birth. After speculating why the hatchlings might be cooing, she ends the poem with,

Maybe, though, cooing is fun. How

to research what transpires

in the head of a hatchling

before it’s hatched –

and why we need to know –

might well be an intimacy

not meant to be trespassed.

‘Hatchlings’ is slightly unusual in the book because it is a single page length poem. And it shows how Hahn can skilfully create a short narrative of speculation. This is a narrative which creates a neat negative of what she achieves in her longer poems. This poem refutes the notion that we can or should fully enter the lives of others; that our speculations might be both fruitless and unrequired. What the poem shows is that Hahn is very conscious of the fact that the way she writes is an examination of lives which, in itself is fraught with danger, offering both pretended intimacy and trespass.

And yet these examinations are part of Hahn’s undoubted power. The sequence ‘Ashes’ follows on from ‘Hatchlings’, and examines her own responses to the possibility that her father has lost or at best mislaid her mother’s ashes. In a series of five-line, tanka-ish poem sections, Hahn explores those reactions. One of these sections runs,

In my kitchen, logs blink in the fire –

through blinds, the wind blusters and

browbeaten trees creak in the orchard.

The rain pours then stops for sun. If

he lost Mother’s ashes what more could I stand?

The concentration on description, which emerges into a powerful emotion is, perhaps, one kind of formulation those of us unpractised in Japanese poetry might expect. The words ‘blink’, ‘blusters’ and ‘browbeaten’ lead us into the final line. Their atmosphere is simultaneously querulous and directive. Via the penultimate line with its clear monosyllables and strong rhythm, we move into the last line. Again, this is a line stripped of both adjectives and emotive verbs. The verbs in the line ‘lost’ and ‘stand’ are positioned at either end of the line to hold it in the tension created by the ‘If’ at the end of the previous line. Its power again lies in its simplicity and clarity. This is a power which has no need of explication or defending.

by Ian Pople