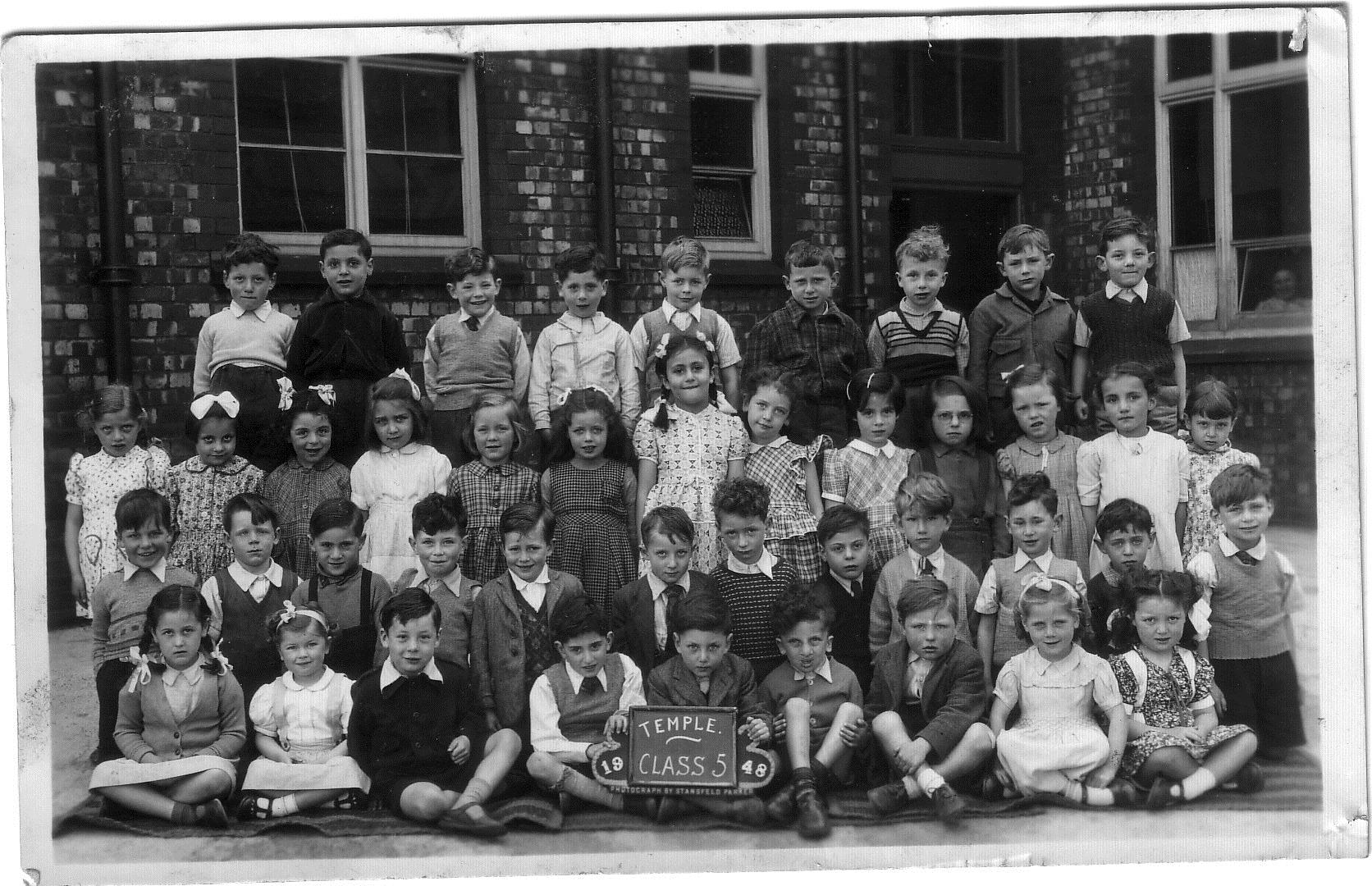

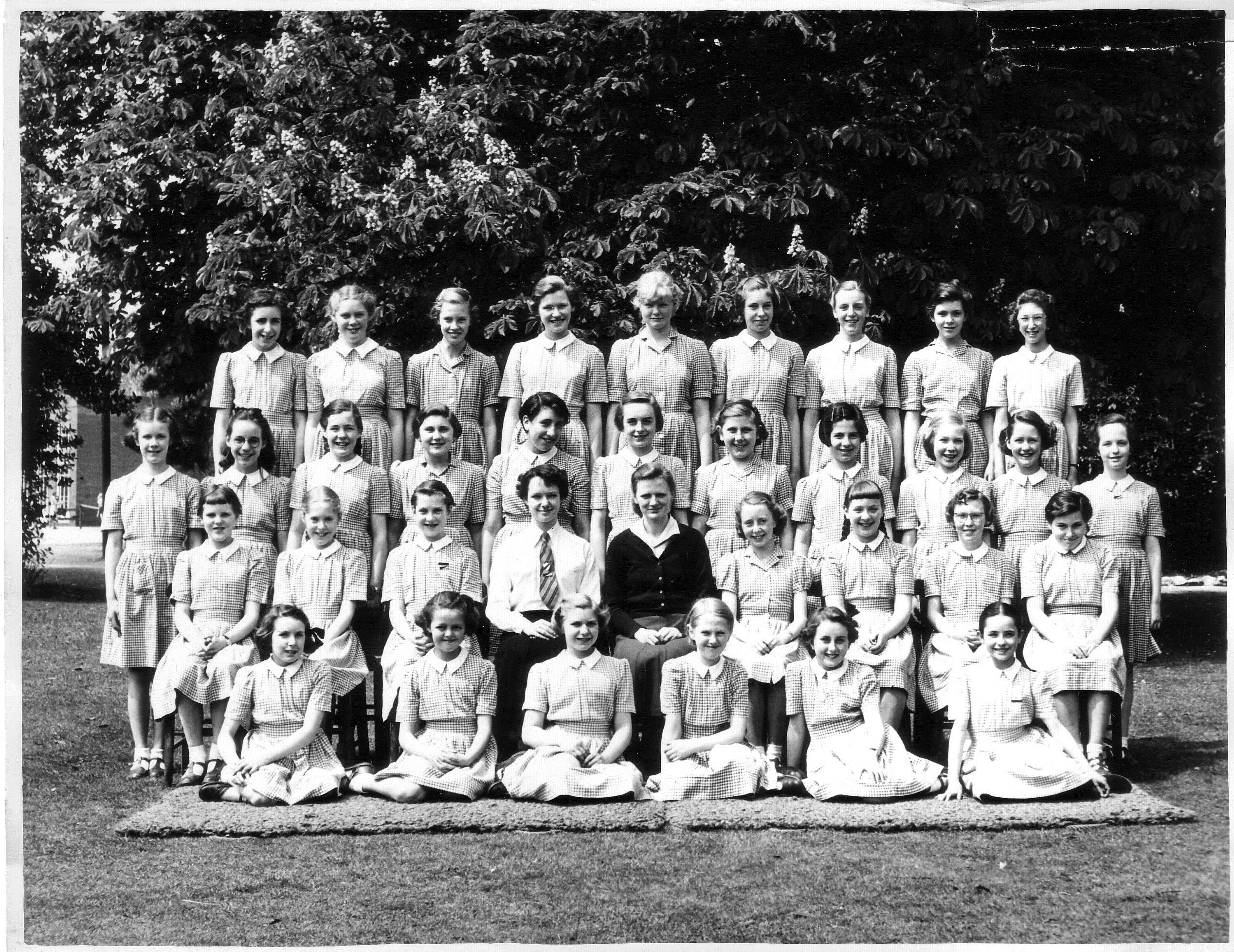

When I was thirteen, my life changed from black and white to Technicolour. This, though obviously metaphorical, at some level feels literally true. We moved house that year (1956), from a semi-detached house in north Manchester to a larger, detached house in south Manchester, and my memories of the earlier period seem to have no colour in them at all. Certainly the house was darker and gloomier. The new house had bigger rooms, more windows and a larger garden, and it was in an area with many more trees. I had also recently moved from an inner-city lower middle class/working class primary school to a solidly middle class direct grant girls’ high school, which in retrospect also somehow feels like a lightening, and a coming-into-colour.

There is of course one obvious explanation for this chromaticising of my memory. Colour photography was newly available at almost exactly this time. When I look through our old family photo albums, everything is black and white – in fact right through into the early 1960s. And then, around 1956, the occasional colour photo turns up. Here is one of my sisters and me, inexplicably inserted among pages of black-and-white photos, dated 1956 on the back.

The effect is something like the 1998 film, Pleasantville, in which a teenage brother and sister are transported through their television set into the black-and-white world of a 1950s sitcom, a world which gradually takes on touches of colour as its inhabitants discover emotions, freedom from rigid social conventions, and sexual liberation. I mean the surprising and – at first – fleeting appearance of colour in my black-and-white world, not the fictional cinematic explanation. And yet I suppose I am talking about a kind of liberation, which colour seems to connote.

At the cinema too we were now seeing more films in colour. Although Technicolor itself dates from the 1920s and 1930s, and home movies had used colour film for a while, it was only in the 1950s that colour film became widespread, after a successful 1950 anti-trust case against Technicolor and the simultaneous development of lower-cost colour film. Eastman Color was crucial here, and so twenty years after his death, and still forty years before I came to his city, where I lived for ten years, George Eastman of Rochester, New York, already figured in my life. Steve Neale has traced the history of Technicolor:

In fact, the value of colour to the film industry fluctuated during the 1950s and 1960s as the relationship of the industry to television, and as the importance of colour within television, themselves shifted and changed. The use of colour in film production increased steadily from 1935 to 1955, accelerating in particular during the early 1950s until colour films comprised some 50 per cent of total US output… It was only during the mid-1960s, when television had converted to colour, that the use of colour in the cinema became virtually universal.

We know very well that a switch to colour within a film (The Wizard of Oz is the obvious example) can signify transition into a fantasy world, or at least a different world. (In Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire the coming-into-colour signifies the angels’ full immersion in the ‘real’ world of everyday life.) So the effect of adjusting from black-and-white films to the new colour cinema must have been something similar. In a context in which reality has been conventionally represented in black and white, the introduction of colour was bound to register a kind of exotic shift. The history and technologies of colour cinema are a fairly new, and fast expanding, field in film studies, but I haven’t found anything yet that discusses the particular effects on audiences of that moment of re-learning how ‘the real’ may be represented. (Even now, we tend to consider black-and-white footage, whether documentary or fictional, as ‘authentic’ in a certain way.) Of course what I am really interested in here is the reverse effect: the possibility that the immersion in cinematic colour has transformational power in our everyday lives and, more particularly, our memories. My strong suspicion is that my idea that the world became colourful in 1956 was mediated by a visual imagination radically re-organised by the movies. The introduction of colour television in Britain in 1967 no doubt reinforced the effect.

I think there is another, more personal, factor in my emergence into Technicolor. When we moved house in 1956, my grandmother, my father’s mother, moved into a retirement home. She had lived with my parents since their marriage, and therefore with me for my whole life. Widowed within six months of her arrival as a refugee from Germany in 1939, far from any members of her family apart from her son, she did not have many options. In our very discreet and calm household – no fights or arguments, no strong emotions, certainly no mention of unpleasant things – this all seemed like a ‘normal’ arrangement. I didn’t even consider, until much later, that this may have been a rather ghastly situation for both my mother and my grandmother. I also had absolutely no knowledge then of the probable cause of my grandmother’s sadness – the loss of many family members, including her sister Leonie, in the Holocaust. Now I am absolutely sure that the new ‘lightness’ (colour) after the move was very much to do with a general sense of release – not just the absence of my grandmother (who was, it is true, a rather dark and brooding presence, and always dressed in dark colours), but more particularly the lifting of my mother’s depression. After sixteen years of marriage, she was living with just her husband and daughters – including a new baby girl, born in November 1954. I think I am right that from the age of thirteen I was no longer living in black and white.