Rachael Allen, Faber New Poets 9 (Faber and Faber, £5.00).

Rachael Allen, Hypochondria (If a Leaf Falls Press, £5.00).

Rachael Allen & Marie Jacotey, Nights of Poor Sleep (Test Centre, £15.00).

Allen’s debut pamphlet with Faber New Poets in 2014 nostalgically reimagined a suburban adolescence “always expecting/ something to happen.” We traipse round the harbour, the village high street, the local dump, waiting for school to start again.

Bus station, flatlands, LED cloud, TEXACO.

I’m glad it wasn’t just me who spent their summer holidays walking to the petrol station or waiting for the bus into town. What’s unique is the way these defining teenage experiences and memories are infused with the new technology of the internet of the early 2000s. The “trapping net” that settles over the housing estate is as much that feeling that you’d never leave, that this was it, and a sense of these new internet networks that were being mapped onto neighbourhoods. When we found out about MSN Messenger we replaced walking to the Jet garage with sitting on the computer until you got caught by your parents. AOL dial-up, Neopets, Rotten.com, Limewire; for a generation of teenagers, these memories of growing up, going to school, being bored during the holidays, are inseparable from these early experiences on the internet. And the internet of the early 2000s seemed young and messy enough to feel full of potential (for friendships, for learning, for new communities etc). Now the conditions of the internet have changed (and I’m a bit older and more cynical) but for a while it did seem like you could meet anyone ever, find a new, better best friend, or a boyfriend who didn’t go to your school.

Allen’s pamphlet is punctuated by a series of 4chan poems, after the image board hosting site that launched in 2003, home to the best and worst of internet culture. The categorisations of the boards become a way to sort through some of the confusing, troubling, definitional experiences of teenagehood (experiences which sometimes seemed to be amplified by the internet). “Random” named after the anarchic /b/ board, 4chan’s most notorious export, sets the tone:

The reference here is to manic, emo video sensation, Boxxy, whose video for another user on Gaia Online made it onto /b/ in 2009 to much celebration/ridicule. Boxxy’s first video captures the weird possibilities of intimacy during these internet early years (how many Habbo Hotel marriages did I attend?) that Allen’s pamphlet seems to tap into, with all that it brings.

“I told my Gaiaonline buddy friend um uh, ADMIRAL AWESOME, that I would make a video just for him. So I’m doing it, here it is, ADDIE LOVE YOU ARGH HAAH ARGH HAAH ARGH HAAH I LOVE YOU! […] I love you, I love Addie because like he’s really like fun to talk to and stuff and like he’s uh, I met him only like two days ago and we’re like married and it is crazy because we love each other so much. And um ugh we are twinnies like all over the place, it is crazy! His avatar is like a manwhore and I…had a avatar a really long time ago…it was a SLUT AVATAR! […] I don’t know what you look like. And yet here you are, you know what I sound like. You’re a bastard. I’m gonna have to ask you for a picture. […] Now no one will find this funny except for a couple of other people I don’t think, so that’s OK, but you know um…yeah, so, I love Addie, Addiepantsssssaaa…and I know you on Gaia and er you want me to make you a video just say so and I will! Because I probably love you anyway, but attee asked first kinda of…yeah.”

“I told my Gaiaonline buddy friend um uh, ADMIRAL AWESOME, that I would make a video just for him. So I’m doing it, here it is, ADDIE LOVE YOU ARGH HAAH ARGH HAAH ARGH HAAH I LOVE YOU! […] I love you, I love Addie because like he’s really like fun to talk to and stuff and like he’s uh, I met him only like two days ago and we’re like married and it is crazy because we love each other so much. And um ugh we are twinnies like all over the place, it is crazy! His avatar is like a manwhore and I…had a avatar a really long time ago…it was a SLUT AVATAR! […] I don’t know what you look like. And yet here you are, you know what I sound like. You’re a bastard. I’m gonna have to ask you for a picture. […] Now no one will find this funny except for a couple of other people I don’t think, so that’s OK, but you know um…yeah, so, I love Addie, Addiepantsssssaaa…and I know you on Gaia and er you want me to make you a video just say so and I will! Because I probably love you anyway, but attee asked first kinda of…yeah.”

Boxxy’s video captures the strangeness of these faux naïf online <333 relationships <333, where you told someone you luffed them without knowing what they looked like (or how old they were). Her tweenager persona (see Catie Wayne) represents the unsettling mix of innocence and precociousness (about the internet, and about relationships).

First (internet) crushes are ended as quickly as they’re imagined, and Allen has us stuck on “the encroaching ledge of age,” surveying the prospects for our first sexual experiences, “burn[ing] shag bands on hay bales” and “playing at adulthood.” These anonymous boards become sites of admission and confession, and we’re rushed through the 4chan poems like we’re not supposed to spent too long here. The board classifications also become access points to return to some of these memories, though there’s a problem in this returning.

“Sexy Beautiful Women” begins with two girls watching a parent’s “unmarked VHSs” with “shop sweets and gluey underarms.” It quickly escalates…“circus lesbians wrapped themselves around snakes and medieval women ate raw hides of meat.” Innocent enough, I guess, then without pause Allen shifts gear: “and then later Erica Lopez’s cam” – now we’re watching something else, somewhere else, and we seem to get even older and more discerning, able to trace the exact movie “(Squirting Tease Party Erica)” – a discovery which sends us back to what was first revealed or summoned by the VHS tapes: “it was a glittering, stuttering, throwback to some damp afternoons of slow awakening.” All this without pause, before the poem ends back on the /s/ board, which has by this point crowd sourced all of the Ericas: “anyway there’s moar” (now we’re quite the connoisseur) “pages and pages of Ericas so many Ericas you may forget that they’re sort of real somewhere in the world in real life.”

If Allen’s Faber pamphlet is invested in a kind of nostalgia about the internet of the early 2000s (and what it might have seemed to promise), her 2016 pamphlet Hypochondria with If a Leaf Falls Press takes its prompts from a different set of online conditions. Hypochondria is a single, twelve-page poem that reads like a hypochondriac’s browser history (see ‘cyberchondria,’ a term used in 2008 to describe a hypochondria facilitated and exacerbated by the internet). Here the googler plays the medical expert, in complete control of the key word searches (symptoms) and the results (diagnosis).

Pale stool from propranolol

Many of us have probably tried to give Google a keyword prompt, like “heart” in this first line, to try to get the result we’re after, like we already know what we’re looking for. It is to do with my heart. Is it to do with my heart? Googling these first lines we get results for articles like “How fingers can show risk of heart disease,” “Pictures of What Your Nails Say About Your Health,” and “Hidden Heart Disease: 19 Dermatologic Clues You Should Know.” There is a reassuring (but frustrating) feedback loop in the language and diagnoses of these sites. “Pale stool from propranolol” brings up a chat board from nomorepanic.co.uk (“Support is just a click away”) – a website which claims to provide “valuable information for sufferers and carers of people with Panic, Anxiety, Phobias and Obsessive Compulsive Disorders.”

Small lump under collarbone

The reader is asked to make paranoid connections between occurrences in the natural world (clouds? vapour trails? chemtrails?) and the goings on of the body. The searches become increasingly impatient and demanding, and lines are interrupted with key words: “Seroconversion – how long”…“Magnesium deficiency – where swells”…“Herpes virus – how long.” The hypochondriac’s concerns are equally significant and equally serious, and they begin to trigger other symptoms. “Pain in left side under ribs” (how many times have you looked up the symptoms of appendicitis?) is quickly followed up by “Anxiety and trapped gas common.”

What does zika virus do

These are the kinds of things we worry about late at night, seeking comfort and assurance in ten year old medical advice in a chat room. And there’s an ordinariness about some of these searches and some of these ways of thinking. But what is really striking about Hypochondria is the strange intimacy of the searches – how revealing they are in terms of what we might be able to glean about whoever’s doing the googling – and the lasting feeling is a kind of paranoia about how readable (and therefore, valuable) this information is.

Mercury count in Tuna fish

BPA in plastic bottles

Protein present in urine

What could we reasonably assume about the person who googles this? Their gender, sexuality, age, economic background, diet, education? – That’s before we start on any symptoms. One day this information will be sold to insurance companies and exploited by employers. Somewhere a HR spread sheet will be updated and a personalised advert sent for an eye test after I search “Small white flash in front of eyes” a few times.

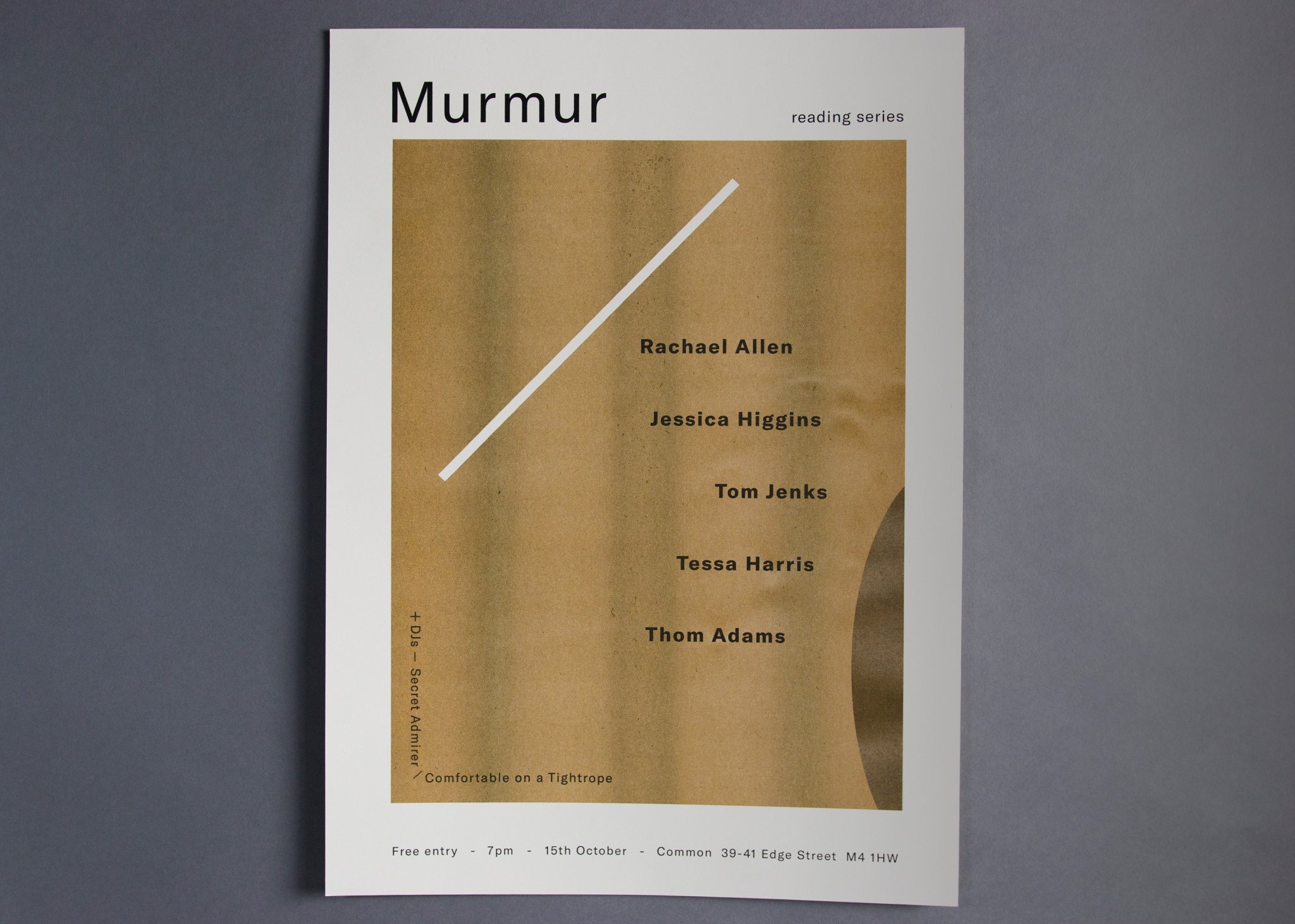

Allen’s latest book is Nights of Poor Sleep, which I saw her read from in October at a new reading series called Murmur.

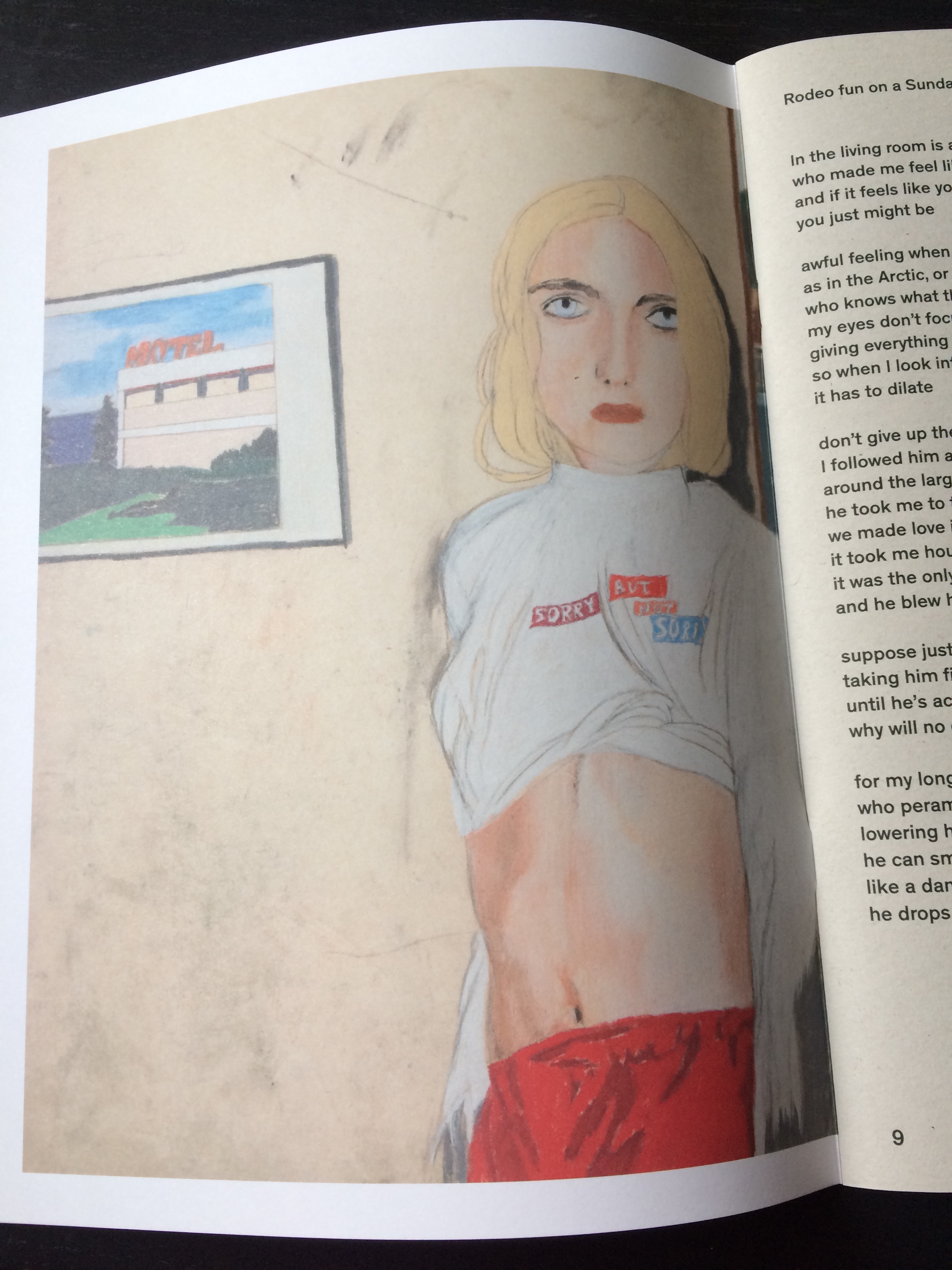

The book is the product of a two-year project between Allen and Marie Jacotey, a London-based artist whose work in pastel and crayon sits somewhere between the comic strip and the selfie. At the start of the reading Allen explains that she found Jacotey’s art useful for thinking about female desire and sexuality, creating the hyper-sexed, hyper-desired character we see throughout Nights of Poor Sleep alongside Jacotey’s illustrations.

like music reverberating under water or a hammock pinged at one end

my safe word couldn’t reach him with his head at my tail

spanking me pinkly into the crawl space

I wore rose gold rings to impress him

(she got there first)

this was outside my character

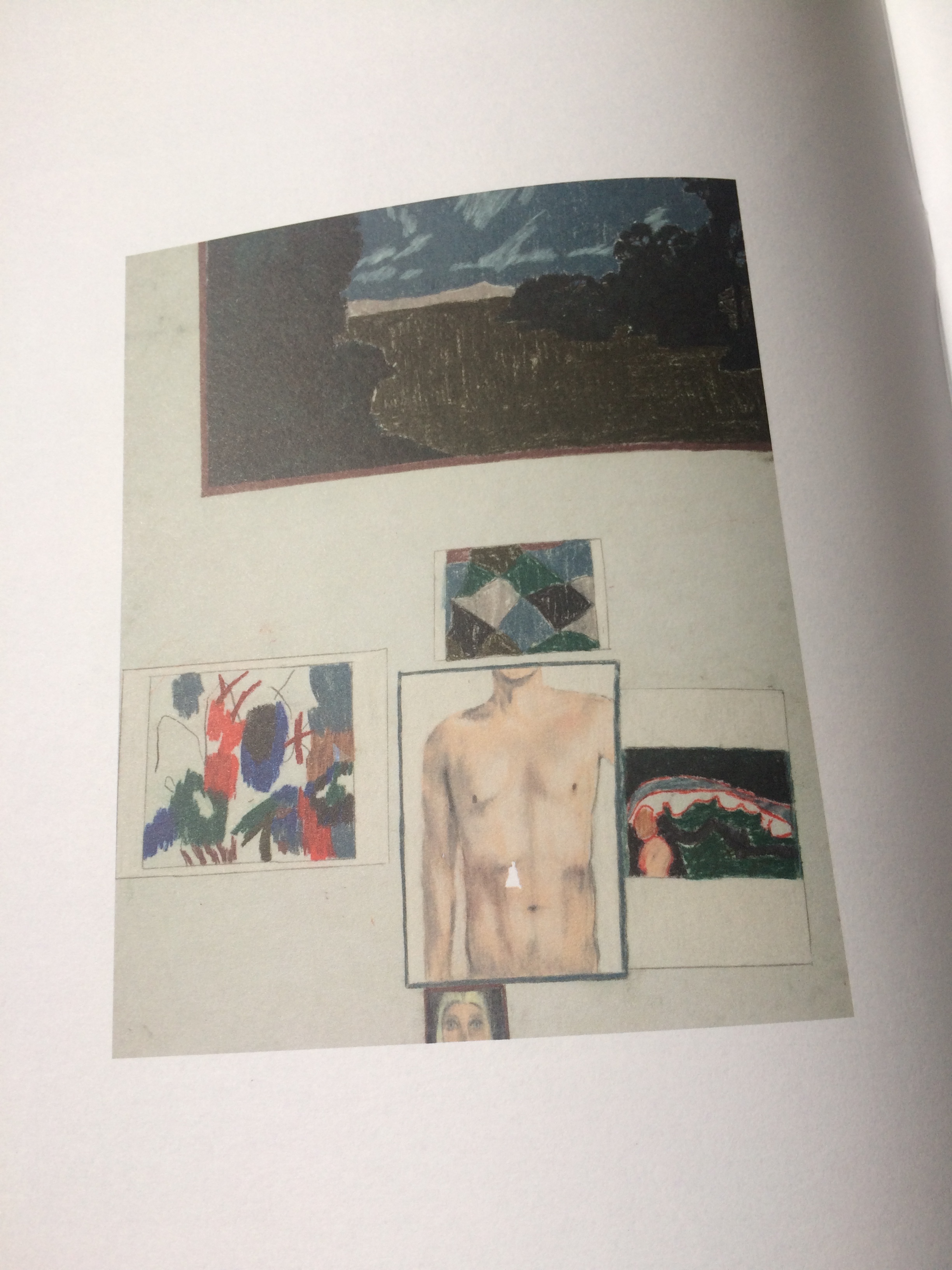

Jacotey’s images are a mix of landscapes, panels with text captions, and portraits that could be at home in an instagram feed. Some seem like collages, or like they’ve been flattened in some way: posters, photographs, and drawings are taped onto studio walls, sheets of paper are layered on top of each other, billboards block landscapes, picture frames are propped up on the floor. I wish there had been some way of showing Jacotey’s images while Allen was reading, not least to get a sense of their original large scale but to help create the captivating, uncanny universe that Allen’s poems occupy. Allen handled the book during the reading like she had to physically negotiate these images. And at times it seems like the book is asking us to take it apart, like it can’t contain itself. Images cross the centre fold and poems just inch over the page; you’d need to take the staples out to get a complete, unobstructed view.

Jacotey’s images are a mix of landscapes, panels with text captions, and portraits that could be at home in an instagram feed. Some seem like collages, or like they’ve been flattened in some way: posters, photographs, and drawings are taped onto studio walls, sheets of paper are layered on top of each other, billboards block landscapes, picture frames are propped up on the floor. I wish there had been some way of showing Jacotey’s images while Allen was reading, not least to get a sense of their original large scale but to help create the captivating, uncanny universe that Allen’s poems occupy. Allen handled the book during the reading like she had to physically negotiate these images. And at times it seems like the book is asking us to take it apart, like it can’t contain itself. Images cross the centre fold and poems just inch over the page; you’d need to take the staples out to get a complete, unobstructed view.

with my breasts taped down

dancing silently on my father’s lap

of course I wake with a start in the

new bedroom

painted blue

in a cacophonous pool of blood

We begin with this nightmare, and are led through a series of “sweaty nights” stuck somewhere between adolescence and adulthood. “NIGTHS OF POOR SLEEP, PUNCTUATED OF AGITED DREAMS AWAKENING FULL OF DOUBTS,” Jacotey puts it in a caption, like we’re drunk or half asleep. Allen moved quickly through the poems like a voice took over, transporting us between motels, rodeos, and Surrey, through a series of ambiguous relationships with men: boyfriends, strangers, “night salesmen,” sailors, “the minor son/ of a minor Duke.” Some seem like they could be ‘normal’ relationships: ‘making love’ and meeting the parents, but in others we see a kind of explosion of her desires: she thinks about taking a group of men home, and elsewhere “grab[s] one by the throat in a frenzy.” But for the most part it seems like she’s on show, being coerced or manipulated, or going through the motions: “my own pleasure/ sustained by/ years of lying / through my teeth.”

I suppose it has happened to many others

if you wear pink dungarees

at an amiable age

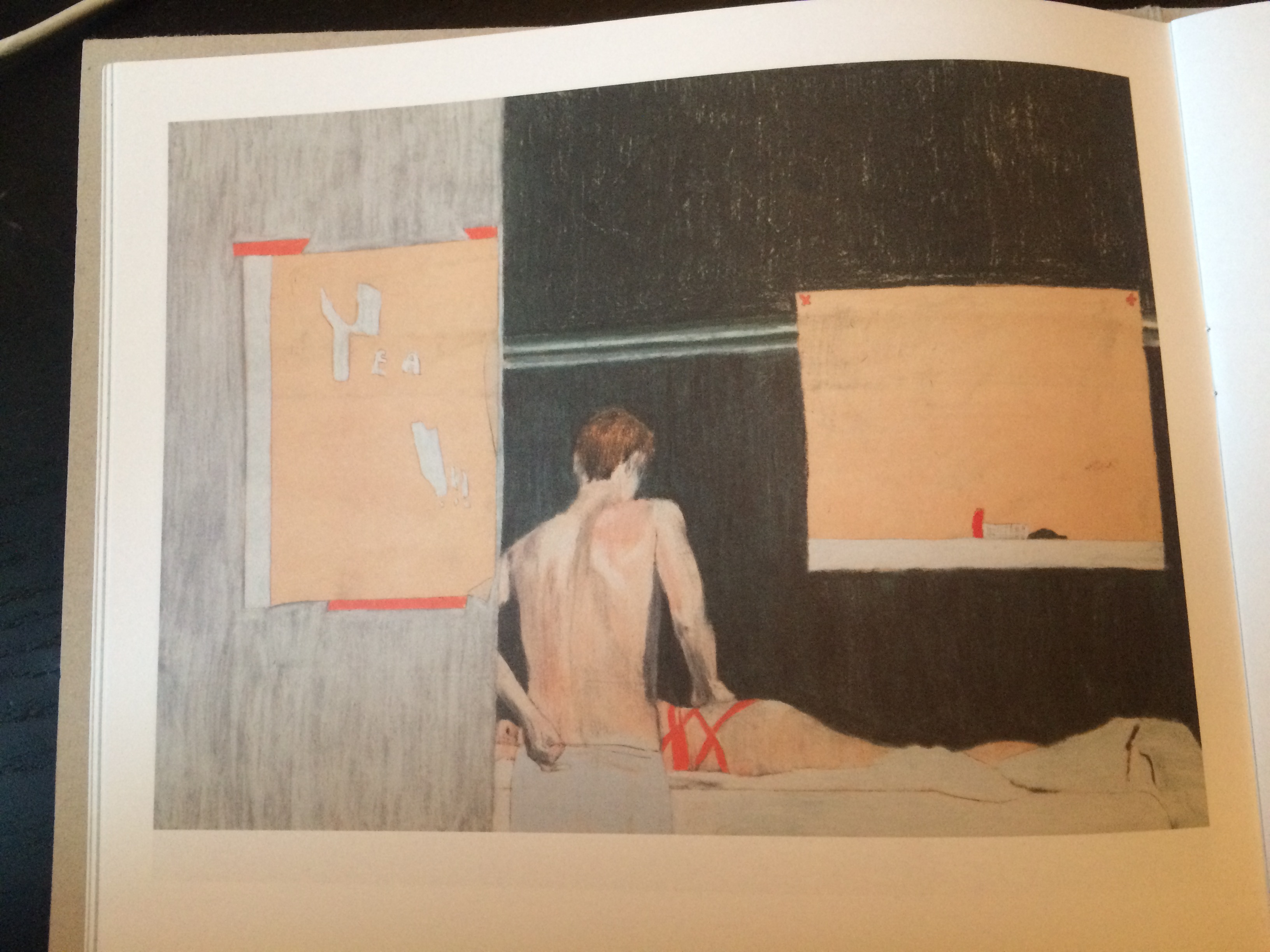

Elsewhere, “night salesmen/ throw themselves against the door/ and I am covered in dread” and we see into a room where a woman is being tied up in the back, taped up with the same tape used to stick a poster to the wall: “yea!!!” it boasts, overenthusiastically. Here Jacotey has us trying doors and interrupting, like the sliding door is about to close on us.

The paradox is that the girl’s desires and sexuality are felt as both a power and a weakness. She seems to be in absolute control of the men around her, through an awareness (and exploitation) of her body, and the kind of power it seems to have. “I wonder which one I might speak to first?” she asks.

when I saunter into the café two streets away

turn left turn left again

when I walk in the door

lipstick on my teeth

a pair of pants hanging around my arm

little smacked-on stain

no one talks when I walk in

and I look everyone in the eye

At the same time, this desire is felt as a kind of burden: an always having to be looked at, always having to be turned on. The girl in Jacotey’s image “Sorry but not sorry” has her long sleeve shirt pulled up to reveal her midriff. She stares at us blankly, challenging us to look elsewhere.

who made me feel like I was falling off a cliff

and if it feels like you’re falling off a cliff

you just might be

She is “so full of it” that “sailors topple off the deck” and “they just can’t stop looking/ at me.” This excess of looking/being looked at manifests as sight loss:

like life is overwhelming when it’s not

everyone looks at me

I’m having problems with my vision, sort of short lines of blue

perhaps becoming blinder

The “zig zags on a blue sky” that for the hypochondriac were an external confirmation of their symptoms return in Nights of Poor Sleep as “an affectation.” The centrefold is structured by Jacotey’s iron bowstring bridge – on second glance an impossible structure, since the X supports have been supplemented with Y Y Y. YES reads the slick in the water below – confirmation of your wildest dreams. Here the sight loss functions like a kind of defence mechanism:

giving everything a crescent edge

so when I look into the pupil of my lover

it has to dilate

Allen’s reading was winding, almost brutal. Hearing these poems aloud you get the full effect of the violence and force of this universe (and of the sharp, devastating wit of this character). I nearly choked when Allen said “pre-ghost” (“he was a god in his blood thirst/ looking out of the window, a pre-ghost/ I know the look of someone newly murdered”) and I could feel myself bracing when Allen started “Rodeo fun on a Sunday”:

it look me hours to lift the pattern from my thigh

it was the only time I wore a blouse

and he blew his nose all over it

Like Allen’s suburban neighbourhood and hypochondriac search history, the world on offer here is endlessly intriguing. Get a copy before it sells out.