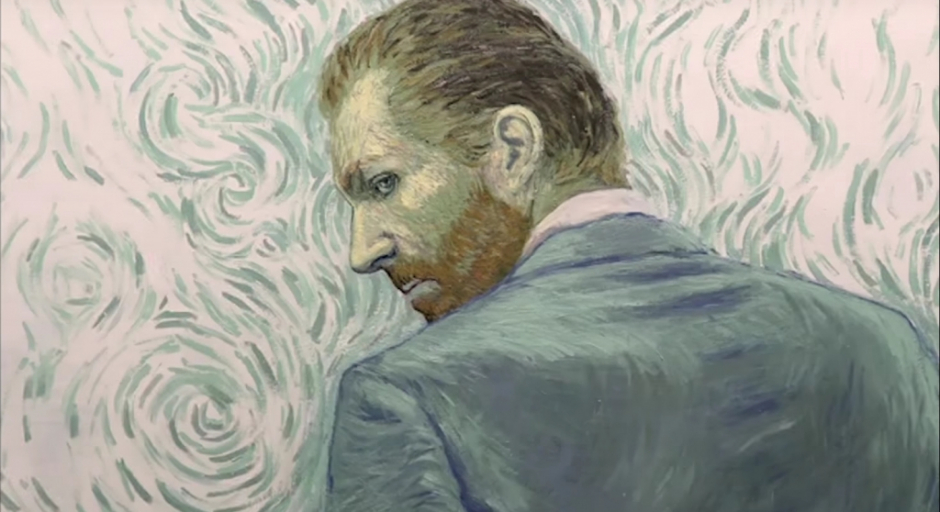

It is testament to the startling depth of film as an art medium that it has so brazenly brushed off all doom-laden interlopers that threatened to sink it – the coming of sound, the collapse of the studio system, the rise of TV, the internet, CGI, 3D, Netflix, and so on. In truth, film is in rude health, as demonstrated when such surprising and startling gems as Loving Vincent appear. This is a production which obliterates the boundaries between artwork, animation, and film-making and does something entirely new and rather unfathomable. Every frame of the film, of which there are over 65,000, has been hand-painted in the style of its subject, Vincent Van Gogh, by a team of hundreds of artists through a complex process of interaction between digital animation, live action footage and the meticulous layering of oils on canvas.

The result is nothing short of fascinating. Far from the static experience of witnessing an art work, the film is frenetic, almost dizzying. Pans, zooms and tracks are conducted in the frantic wriggling of brushstrokes, while small movements, like the curl of smoke from a cigarette, create hypnotic blends of foreground and background, giving a visceral materiality to the cinema screen. The fusion seems almost heretical; it feels devilishly indulgent, like this is neither the way we should experience paintings or films, inviting internal debates about where the parameters of the two art forms should actually be drawn, so to speak.

There are a few curious moments, however, when the film seems to do battle with the abstractions of Van Gogh’s style. Certain close-ups – in particular during flashback scenes drawn in monochrome – become, for fleeting instants, a little too photorealistic. The moments are a strange betrayal, almost, of Van Gogh and his very particular artistic vision; the obsequious camera too much in adoration of its star-studded cast, at times. As such, the endeavour is much more successful for long shots and establishing shots where animated birds flitter through swirled skies and figures stutter across Parisian streets. We are allowed to indulge in the spotting of the various masterworks and then bask in the strange glory of seeing them move – of seeing, for example, the waitress of Café Terrace at Night actually serving her waiting customers. As such, Loving Vincent will resonate longer than comparable attempts at artist biopics, such as Mr Turner and Girl with a Pearl Earring. This is a film which really takes its adoration seriously.

But this is not just artful play, there’s a story being told too. Using the various subjects and landscapes of Van Gogh’s most famous paintings, an investigative narrative is strung together as an acquaintance of the late painter, Armand Roulin (Douglas Booth), is drawn into the mysteries surrounding Vincent’s death. He bounces back and forth between Vincent’s friends and companions to piece together his final hours, weaving together competing theories about suicide or murder, Rashomon-style. As someone entirely ignorant of Van Gogh’s life, I found the story compelling and intriguing, although it veered a little too close to a CSI police procedural at times and some of the poetic reflections of the characters were, occasionally, a tad too on-the-nose.

The cast, who put their all into the script, are a starry roll-call of British hot-property, including the ever-sexy Aiden Turner, an ice-cool Saoirse Ronan, and a heavily-bearded Chris O’Dowd. Most compelling were Helen McCrory as the fastidious and evangelical housekeeper Louise Chevalier and, fresh from his dragon slaying, Jerome Flynn as the troubled and frustrated Doctor Gachet. The strange disjointed juxtaposition of accents and setting aside, the ensemble do a fine job of bringing the slightly threadbare story to life, and a welcome addition of painting-and-character comparison during the end credits does a great service to the casting director.

So, while there may be nits to pick, on the whole the film is a marvel and joy to behold. A staggering achievement of pure craft and vision, it confronts the boundaries and limitations of both art forms and paints over the cracks in bold, defiant strokes.