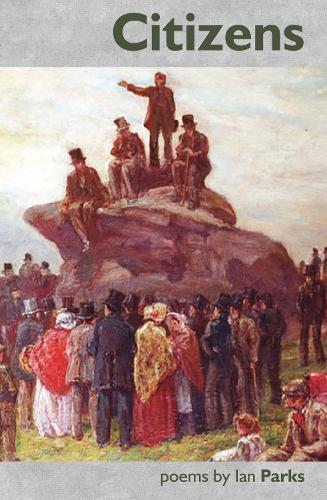

Ian Parks, Citizens (Smokestack Books, £7.99).

Over the years, Ian Parks has produced about a dozen books and pamphlets, from a variety of publishers. His shtick seems to be to have a new book out with a new publisher. But that variety of publisher never seems to diminish or dilute the quality of Parks’ writing, which is, surely, amongst the finest poetry being currently produced in these islands. This short review is of Parks’ latest book, Citizens, but it is also a meditation on why Parks’ writing is not more lauded; although Rory Waterman, no less, has presented on Parks poetry in conferences.

Over the years, Ian Parks has produced about a dozen books and pamphlets, from a variety of publishers. His shtick seems to be to have a new book out with a new publisher. But that variety of publisher never seems to diminish or dilute the quality of Parks’ writing, which is, surely, amongst the finest poetry being currently produced in these islands. This short review is of Parks’ latest book, Citizens, but it is also a meditation on why Parks’ writing is not more lauded; although Rory Waterman, no less, has presented on Parks poetry in conferences.

A lot like the late T.F. Griffin, Parks is an outlier of British poetry whose writing was spotted and praised early by figures whose judgement we would do well attend to. With Griffin, it was Philip Larkin who provided the encomium; with Parks, it is Donald Davie, who commented that Park’s voice was ‘spare, lyrical, memorable and intense’, and remarked on ‘the sheer force of his poetic identity.’ Over the years, that voice has become more particularised; an Ian Parks poem is instantly recognisable. But the lyricism, which has characterised his writing from those early days, has remained as intense, as spare and as memorable as ever.

If the political is a major dynamic in a book called ‘Citizens’, Parks imbues that dynamic with an adroit intensity, which moves the poetry far away from agitprop, or the poetry slam. Parks, who wrote his PhD on Chartism, and whose father was a miner, often embeds the political in lives lived in the North, particularly around the old Yorkshire coalfield. But it is the lives which matter and the message is the life. In the opening and title poem, ‘Citizens’, ‘Free agents’ are out ‘our used car swerving through the new estates’. But ‘free’ as they may be, ‘We travelled incognito and we didn’t cast a vote’. And in the final verse, ‘The cities had no feature and the landscape had no soul./ Girls waved from the corner as we hit the open road,/ our every exit covered by a camera on a pole.’

This opening poem sets the tone in a number of important ways. Firstly, Parks shows the citizens as actually deracinated, not really citizens at all; they feel the need to travel incognito and they do not use their vote. When they travel, they are not really ‘free agents’ either, because they are watched not only by CCTV cameras, but also by these strange and slightly sinister girls who wave at them. But Parks poetic skill is also to use the word ‘agents’ to deadly effect here; the pun sets up the resonance of the clandestine that runs throughout the poem.

The other aspect of tone which is evidenced here is the sense that, with Parks, the line is the cadence. Parks’ lines tend to end with what used to be known as a ‘masculine’ stress, i.e. the lines end with a stressed syllable. Often that stressed syllable is contained within a lexical monosyllable. In ‘Citizens’ the line-final words are: ‘way’, ‘estates’, ‘rape’, ‘sky’, ‘vote’, ‘beach’, ‘fade’, ‘stars’, ‘blue’, ‘soul’, ‘road’ and ‘pole’. But the line endings never feel clunky or end-stopped. In part that is because the line endings contain subtle assonances and half-rhymes; but also, Parks’ consummate skill is to sway the music along the line both towards and away from those line endings. These lines cry out to be read aloud.

In the centre of Citizens, is a lovely, autobiographical prose piece ‘Ella’. In its own way, it is as poignant and careful as Robert Lowell’s ’91 Revere Street’, which punctuates Lowell’s collection Life Studies. Ian Parks’ ‘Ella’ recounts his and his father’s love of jazz, particularly the singing of Ella Fitzgerald. Parks’ father is a miner, who is also an amateur singer in pubs and clubs, but, obviously, a very good singer, who’d had ambitions to become professional ‘had he not got married, and had me’. Parks father ‘didn’t sing a song. He embraced it’. When Parks’ father has some spare money, he takes Ian with him to see Ella Fitzgerald sing at what is clearly, Ronnie Scott’s old club in Frith Street. They both feel conspicuously out of place ‘among the black polo necks, the tweed jacket, and goatees.’ And, then, almost making things worse it seems, when Ella comes on stage, she senses the young Ian’s attention and starts singing Billie Holliday’s ‘The Man I love’ directly towards him. This is a wonderful piece of writing; crisp, piercing, beautifully turned. Much like everything else in this lovely new book.