In 2015, the multi-Emmy award-winning television producer Mark Burnett, brains behind such reality shows as Survivor and The Apprentice, launched Lucha Underground, a weekly episodic professional wrestling show realised in partnership with Hollywood director Robert Rodriguez. Bringing wrestlers from the American independent scene and Mexico’s AAA promotion together with supernatural storylines and a pulp-cinematic production style familiar to followers of Rodriguez’s output, the show has experienced some success in bridging the current gap between wrestling audiences and the rest of the viewing public, having been scooped up by Netflix earlier this year. Leaving to one side for a moment the actual quality of the show (consistently very high), the success of Lucha Underground seems symptomatic of the fact that Mexican professional wrestling – or Lucha Libre, as it is often referred to both inside and outside of Mexico – has long possessed a further-reaching aesthetic caché than its counterparts in wrestling’s other traditional heartlands of North America, Japan and the United Kingdom.

Note “aesthetic”: at least here in the UK, Lucha Libre’s stock imagery of masks, capes and muscles seems synonymous with a certain idea of Mexican-ness to the extent that a hip burrito joint can name itself after the sport, or a cultural festival celebrating Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking cultures (namely, the ¡Vamos! Festival in Newcastle) can organise an annual card of exhibition matches as part of their programming. When the imagery of North American wrestling re-surfaces in the general public imaginary – as we’re currently seeing in conjunction with Netflix’s GLOW series – it generally does so slathered in irony and retro signifiers pertaining to the eighties or nineties. Lucha Libre, by contrast, is rendered relatively timeless both by its exoticism to anglophone audiences and by the fact that the sport genuinely does cling to certain traditions – like the public secrecy of masked wrestlers’ real identities – more tightly than some of its international cousins.

All of this is to suggest that in spite of the current boom in the UK independent wrestling scene (a topic which, despite the consuming interest it holds for this reviewer, is admittedly not a natural fit for a publication like The Manchester Review), Lucha Libre World’s showcase event at the Albert Hall can be placed in a different context to the shows orchestrated in Manchester and elsewhere by companies such as Progress and Fight Club Pro. The crowd, whose numbers are perhaps not quite up there with the majority of Albert Hall events but are still pretty decent for a wrestling show, does not for the most part appear to be made up of dyed-in-the-wool wrestling fans. One telltale sign: the gender balance is decidedly more, well, balanced, than the majority of UK independent wrestling shows. Another: I am one of only a handful of individuals in the Albert Hall that evening wearing a wrestling t-shirt.

A third: late in the night when one of the performers drags his opponent over to the ringside seating and barks at the audience, very few of these spectators get up out of their seats and clear the area. Most attendees at a Progress show would have immediately read the cue and understood that the gesticulating performer wanted to throw his victim across the first few rows of chairs, but tonight’s performers are forced to improvise an alternative. These demographic observations are relevant because wrestling is a performance medium that thrives on audience participation. In the case of most of the UK companies whose attendance figures are currently on the up, this usually means informed participation: a ticket to a Progress show means, as much as anything, a chance to get in on a series of in-jokes shared by audience and performers, and an invitation to share in the hype accompanying stars on the rise. Progress fans in particular have appropriated the supporter identity proper to football clubs, labelling themselves as “ultras”, and the promotion has reciprocated by offering fans the opportunity to buy “season tickets” for their more-or-less monthly shows at Camden’s Electric Ballroom. Lucha Libre World, by contrast, are here in Manchester for their only show this year (although a two-day residency at Bethnal Green’s York Hall venue follows on the Friday and Saturday), with no promise of a punctual return. This audience has gathered for the opportunity to see a one-off spectacle of Lucha Libre, for reasons that are presumably as manifold as the sport’s applications in popular culture, and which may have little to do with an overriding interest in wrestling as whole. The mechanics employed by the performers to engage the crowd have therefore to be all the more acute if the show is to succeed on its own terms.

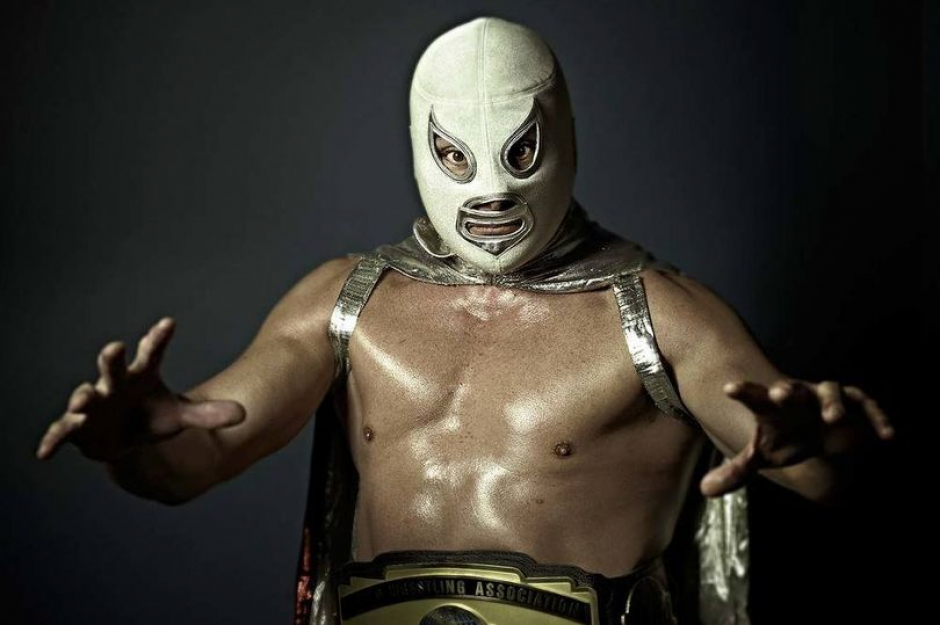

Reader, they are. There’s a particular kind of routine practiced by Lucha Libre villains (or rudos) that I’ve seen many times over in clips of the sport: after the hero (or técnico) makes an appeal for support from the crowd and is met with cheers, the villain will turn to each side of the room successively with an expression of disgusted surprise; they might then choose to embellish this by swinging their arm above their head in a circling motion (as if to indicate “all of you”), following this up with a gesture involving both arms that translates roughly as “up yours”. We get a lot of this kind of gesticulating tonight, particularly in the main event, a match between the rudo team of Bandido and Silver King and the técnico duo of El Santo Jr. (grandson of supreme Lucha legend and all-time Mexican pop culture icon El Santo) and El Hijo del Santo (his father, and a highly revered performer in his own right), and it never fails to draw the requisite boos. Stark divisions between good and evil protagonists are absolutely foundational to the spectacle of Lucha Libre, and it’s this relative moral simplicity (one which echoes the WWF programming of the 1980s but which is increasingly rare in anglophone wrestling today) that enables Lucha Libre World’s performers to connect with the Albert Hall crowd as effectively as they do. The performers on display across the four matches vary in terms of the depth and character of their talent – they range from recently-graduated trainees of the London Lucha School to thirty-year veterans, and from heavyweight to somewhere below super-lightweight (Muñeca de Trapo, whose name translates as ‘ragdoll’ and who plays that gimmick very well) – but all succeed in getting the right kind of rise out of the audience, and in integrating these responses into their performance in turn.

The loudest reception of the night is reserved for the penultimate contest, featuring the rudo team of El Hijo de Fishman and Puro Britanico against Cassius and Cassandro. The latter two are not técnicos precisely, but exóticos, male wrestlers whose characters set out to undermine the typical machismo of Lucha Libre through effeminate, camp and flamboyant costumes and mannerisms. Cassius and Cassandro are a generation apart – the latter is a veteran of the Mexican touring circuit, while Cassius is a rising star in London’s Lucha Britannia promotion – but are both equally effective in putting across the exótico tradition to the Albert Hall audience. While exóticos in Mexico play the rudo role just as often as the técnico, the audience’s sympathies were only ever likely to fall one way for this match: through exaggerated bodily gestures alone, Cassius and Cassandro manage to turn themselves into emblems of free-spiritedness and joie de vivre, while their opponents excel in the role of dour, sadistic cloggers. The crowd lays down chants of encouragement during spells of action when the rudos are on top and roars into life when the exóticos fight back. The story is very simple – not so much a battle between good and evil as between expression and repression – and everyone gets to help drive it to its conclusion. At the end, the good guys win, just as they do in the main event. One of the great benefits of professional wrestling as an entertainment medium is that it mimics the adrenaline of legitimate sports while still reserving the potential to send all spectators home happy. From the feeling in the room after the final bell, it’s clear that Lucha Libre World have achieved that feat for the majority of the Albert Hall audience, many of whom have no doubt learned to read the language of Mexican wrestling for the first time over the course of this evening.