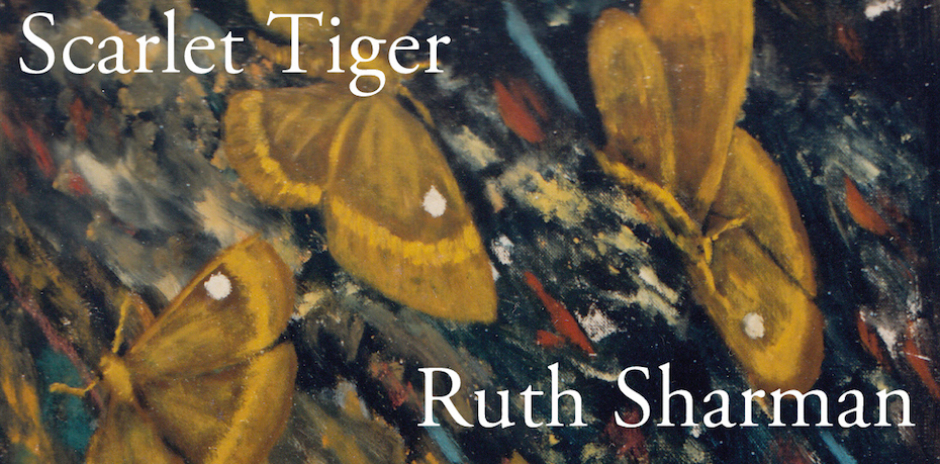

Ruth Sharman’s Scarlet Tiger comes some time after her first collection, Birth of the Owl Butterflies; its title poem a second place winner in the Arvon Poetry Competition. In this book too, there are poems about butterflies and Sharman’s father. Indeed the interest in, near obsession with, butterflies is clearly inherited from her father, as a number of these poems attest.

Sharman’s poems move down the page with a sure-footed delicacy. In ‘The White Room’, the poem accumulates early detail: ‘…the glimmer/ of crab apples. Or a cat sprawled/ on a roof. Susan Trickett’s/ ample green bosom pressed/ against the rungs of a stepladder/ two doors down, anything/ that anchored you still to the earth.’ These details move us to that final perception of the mental state of the observer. That suggestion that things are not quite as they might be is reinforced by the next line, ‘Every sudden flash of wings/ would count.’ The reader is not told what the wings would count for. But what we get at the end of the poem is the portrait of the observer sitting in a window alcove, ‘…with a book/ on summer afternoons/ half-listening to your mother/ rattling the tea things downstairs/ and that voice calling/ from the evergreens: Two cows,/ Taffy. Take two cows, Taffy. Take.’ Sharman’s short lines move the reader neatly through these accumulations, but the accumulations often subtly subvert the expectations they themselves accrete.

These lines also give a flavour of Sharman’s voice. It is essentially unadorned, but it is a voice which draws the lines down the page quietly but surely. There is that unusual noun phrase ‘a glimmer of crab-apples’, but there is little ‘poetic’ about the writing. In the second set of quoted lines, the participles ‘half-listening’, ‘rattling’, ‘calling’, create a suspension in the action. Thus Sharman never over-sells her insight; the language never obtrudes in the telling.

Identity in Sharman’s writing is mutable and often quite fragile. Masculinity, in particular, in a book dedicated ‘for my father and my son’, is never certain. If Sharman’s father is adept with a killing jar, he is also ‘shy, awkward, complex’. If he is capable of ‘running at the double to fetch/ the cap he left in a field five miles back’, he is also ‘most at home in bogs/ and on tangled hillsides watching/ for the likes of this butterfly/ that’s just come flittering over/ the garden fence’ (‘Talking to myself’). But he is also the father on morphine at the end of his life. If Sharman’s son has a childhood stammer, he also declares that the best present he could have for Christmas is to see God. And he is also the son whose flight path she follows on her computer screen as he flies out to Kathmandu. And these are not only poems which see that identity enacted in filial relationships. Sharman’s quiet skill is to show how identity within the home reaches out and finds its place in a much wider and various world.

Sharman refines and renders her poems with a perfectionist’s eye; so each poem has an inevitability and robustness which fits with Yeats’ sense of the poem coming together like a well-made box clicking into place. In a better world, Sharman’s writing would be as recognised as that of poets as different from her as Vicki Feaver and Selima Hill.