The Peony Pavilion was originally a play written by Tang Xianzu and first performed in 1598. Most commonly and traditionally performed as an opera with a running time of over twenty hours, this retelling came about in 2008 when the then artistic director of the Chinese National Ballet, Zhao Ruheng, approached choreographer Fei Bo to turn this opera into a two hour ballet (with director Li Liuyu). The result, Julia Fawcett (Chief Executive of the Lowry Theatre) states, is a performance of ‘sheer spectacle and beauty’. In many ways, Fawcett is correct: the seventy strong ensemble gave the piece an impressive scale, especially during the wedding scene as the entire corps de ballet, wearing bright red, ran in a circle as a mass of red petals fall from the ceiling. Just as grandiose was the pavilion in the centre of the stage which became a spectacle not only for the audience, but for the dancers. The corps de ballet were framed around the pavilion as their focal point as it raised and tilted during scenes such as the erotic duet between the two protagonists, thereafter becoming a site for motifs of re-enactment of this love scene.

Besides the spectacle of the performance, the plot of the ballet (told to us at the beginning of the performance by the choreographer) was an interesting exploration of desire. Whilst on the pavilion, the female protagonist Du Liniang has an erotic dream about Liu Mengmei. When she awakes she is accompanied by two alter egos: Kunqu Liniang (who represents the traditional Kunqu opera style) and the Flower Goddess Liniang. Now awake, Du Liniang reminisces about her dream encounter and, touching herself, asks the Flower Goddess to take her back to her dream to be with Liu Mengmei. Instead, Du Liniang is taken to the underworld; for her desire to be fulfilled, she has to die.

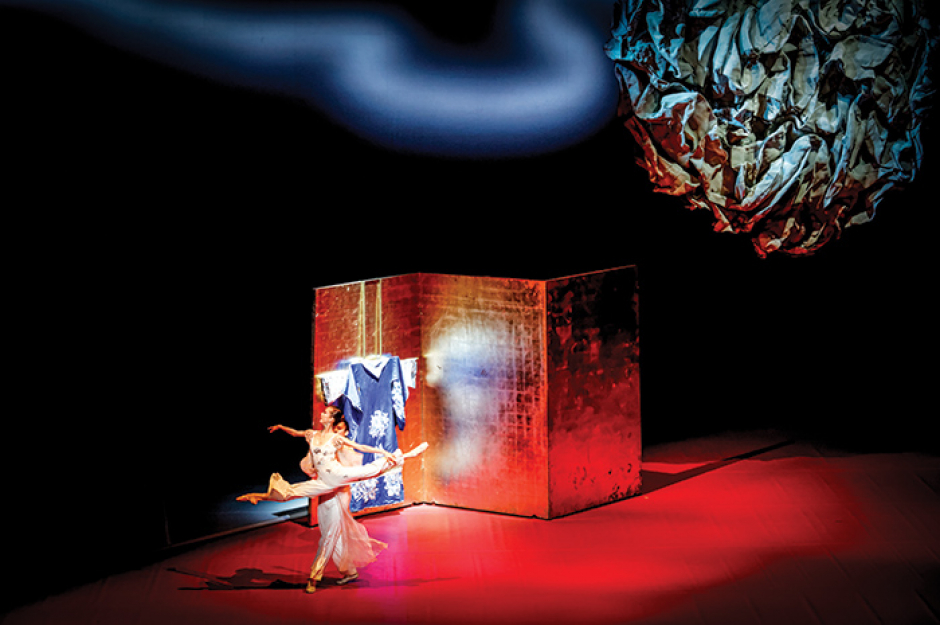

In the second act, Liu Mengmei appears to have had a parallel dream about Du Liniang, and as his object of desire is unattainable (Du Liniang is in the underworld), she is thus metonymised through her clothing when Liu Mengmei dances erotically with her dress. The Infernal Judge of the underworld eventually sends Du Liniang back ‘to the mortal world to realise her dream’ and Du Liniang and her alter egos turn into one unified subject. Du Liniang and Liu Mengmei search for each other in the mortal world and choreographically keep reaching for each other, yet ultimately miss when they are about to touch. The end of the ballet sees them united and they marry with a celebration of ‘mortals, ghosts and gods’. While desire splits Du Liniang into three and the initial promise of fulfilment of this desire leads to her death, the ballet ends with the reunification of Du Liniang’s character through the social structure of marriage, which becomes the acceptable (and celebrated) way to experience this desire.

Designer Emi Wada’s costumes in the ballet not only played a key role in delineating the separate alter egos through the colours red, white and blue, but elements of Du Liniang’s costume also came to stand in for the erotic act. Du Liniang’s dress became a symbol of her unobtainability, while the pointe shoe (and the naked foot) became a symbol for undressing. In the initial love scene, Liu Mengmei slowly removes one of Du Liniang’s pointe shoes from her foot whilst the other remains; Du Liniang remains always in the process of undressing. As a result she dances with just one shoe on and flexes her bare foot – drawing attention to its nakedness without the restrictions of the pointe shoe. Once she wakes up from the dream, Du Liniang re-enacts the undressing by removing her own shoes whilse caressing her body on the pavilion. The corps de ballet wear only one shoe in the underworld as a reminder of the erotic act and likewise flex their bare foot as they développé.

There was an almost unacknowledged class aspect to the ballet where Du Liniang is said to be ‘a girl from a rich family’ and the ‘reality’ that Du Liniang so detests is represented through a working class and ‘disordered’ peasant town. These dancers wore brown, were acting drunk and bawdy and there were haystacks hanging from the ceiling. It is this reality from which Du Liniang wants to escape, which she does through her marriage to ‘scholar’ Lio Mengmei. Ultimately, the ballet represented a bourgeois fantasy of desire in which the structures of marriage can fulfil and unify the self. In the context of the Maoist history of The National Ballet of China and the more communist ballets like The Red Detachment of Women, this ballet represents a new edition to the company’s repertoire that marks a distinct shift in its politics.