It was a strange room, hung with tapestries no one knew the meaning of, symbols, pictograms of all sorts. The colour red figured prominently. Music played quietly in the background, incongruous music, slightly manic, but which no one was listening to anyway. It was there to carry the dips in conversation, of which there happened to be almost none.

‘Why do you surround yourself with this stuff, Hetty?’ someone shouted across the room to the host.

‘What’s that?’

All down the table the glasses were full of wine, the plates littered with scraps. Between the eleven of them there were at least three conversations in full bloom.

‘Why do you…?’

‘Because I have oodles and oodles of taste, dear heart.’ Which was followed by laughter all round. You couldn’t not laugh. To not laugh would have amounted to a minor betrayal, and Paul laughed with the rest of them. The wine helped.

He was there on his own, Paul. Katya had seen to that, had persuaded him he must go, that someone ought to be there.

To his one side was Candice. Opposite him, through the candles, was Oscar.

‘What was I saying?’ said Candice.

‘You were talking about the perils of cleaning,’ said Oscar, and did a little thing with his eyebrows.

‘Uh! If I don’t go through my place at least once a week my skin begins to crawl.’

‘But you don’t seem the messy sort.’

‘Doesn’t matter. I need to know I’ve done it.’

‘Every week? Does the dust even have time to settle?’

‘Of course!’ This was pronounced with a mixture of pride and indignation.

‘And what would happen if you just left it?’

‘I…’

‘I mean it’s only going to get so thick, isn’t it? Tell her, Paul. It only gets so thick and then it stops. Isn’t that right?’

Paul took a sip of wine and put his glass down.

‘I don’t know about that.’

‘I mean, imagine it: shut the door on a room and come back in ten years, how much dust has settled? Come back in twenty, a hundred. How much more? After a while it would all look the same. There’s a limit. An obvious limit.’

‘And you’ve approached this limit, how many times?’ said Paul.

‘Ha! Touche.’

‘Eww!’ This was Candice. ‘I lived in this house once, right after I moved out of home. I can’t even describe it. Nobody cleaned a thing. Every time I stepped through the front door I’d run for it. I ended up eating all my meals on my bed. It was just disgusting.’

‘What’s that look for?’ said Oscar.

‘I was just thinking about my own home,’ said Paul. ‘When I was growing up.’

‘Why? What?’

‘My mom wasn’t the best housekeeper.’

Oscar and Candice stared at him, clearly waiting for more.

‘She was preoccupied,’ he said.

‘With what?’ said Candice.

‘She was an artist…’

‘I didn’t know that. Was she very successful?’

‘Depends on your definition of “success.” She never made much money, but she got to play around with the things that fascinated her.’

‘She was a pretty amazing woman, actually,’ said Oscar. ‘Very unusual.’

‘You knew her?’

Oscar nodded, looking from Candice to Paul. ‘I met her a few times.’

‘Yes, you did,’ said Paul.

‘She’s not…?’

‘No,’ said Paul. ‘She passed away about ten years ago. Smoker.’

‘Shame.’

‘Yeah.’

At one end of the table there was a roar of laughter, and the three of them turned to look. The effects of the wine were evidently in full swing. Four people, including the host, had spoons dangling from the ends of their noses.

‘I can do that,’ said Oscar.

‘How nice for you,’ said Candice, and turning to Paul, ‘So…, you grew up in an artist’s nest.’

‘That’s one way of putting it. “Mess” is probably more accurate.’

‘What was it like?’

‘I ended up doing my own laundry because sometimes she’d forget a whole load at the laundromat. I learned how to cook a bit.’

‘Did you do the cleaning?’

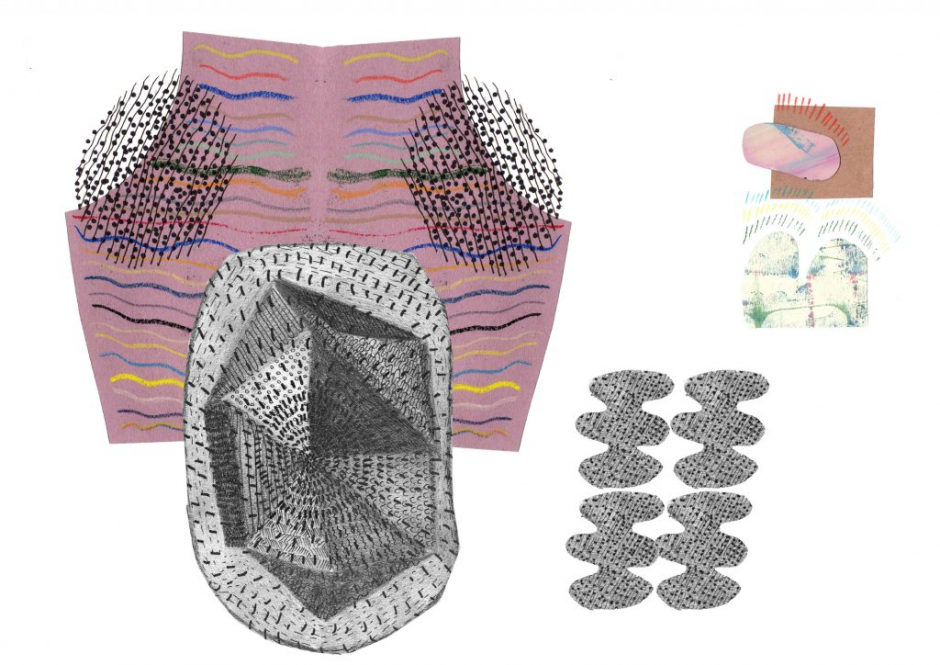

‘Not really. I mean, when I was still there it wasn’t quite so bad. She kept up with it. Sort of. But when I left it went to a whole new level. She had this apartment, a big place, just crammed with… with junk. She had all her paints and everything set up in this one room, these huge plywood boards, four by eights, sitting on top of the furniture so you couldn’t really sit anywhere, but there was all this space for her to spread out what she was working on. And the rest of the place was a disaster. I took my daughter around a few times. She was a year old or maybe two. And my mom would offer her something to drink and I’d look at the cup and just hope there wasn’t anything growing in it before she poured the juice in. There was stuff everywhere. One time I brought round Katya’s parents…’

‘Poor Katya,’ said Oscar. ‘You said…’

‘She’s good. Still a bit sore, but on the mend.’

‘Thank goodness she’s so tough,’ said Candice.

‘She’s tough, all right. Looking forward to having things back to normal. Getting out again.’

‘It’s no fun being cooped up.’

‘No,’ said Paul. ‘No fun… Anyway, I had her parents around to my mom’s place this one time. One of the few times they met. And I had Evelyn with us. Our daughter,’ said Paul, turning to Candice.

‘Oh, I’ve met Evelyn.’

‘Yeah?’

‘All the kids were at the last one of these. Remember?’

‘That’s right. I remember now,’ said Paul, rubbing his forehead with the palm of his hand. ‘Well, I had Evelyn with us, and we hadn’t been at my mom’s very long. Katya’s parents had gone into the front room, my mom was there, showing them stuff, and I noticed that smell. I grew up with it, the smell of dead mice. And I looked down and there it was. Right at my feet, on the carpet. Right in the middle of everything. I put Evelyn down and scooped it up, and flushed it down the toilet.’

‘Nice.’

‘And that,’ said Paul, ‘gives you the basic idea.’

‘Did you ever go round and help her?’ said Candice. ‘I mean, with the cleaning?’

‘No.’

‘Why not?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘You should hear…’ said Oscar, his words beginning to run into one another, ‘you should hear what they did with her coffin…’

Candice turned to Paul, wearing a look that as much as said, I can’t believe he just said that, but all the same I want to hear, don’t I?

Without looking, Paul sensed that some of the others were listening in now as well.

‘It’s not so dramatic, really. We painted it.’

‘”We”?’

‘I have older sisters. We painted it and covered it with pictures, and things we remembered her saying. The names of her grand-children. Things like that. Stuff she used to use in her art.’

There was a sudden dip in the conversation all round the table, and Paul’s words were left hanging in the stillness.

For the first time it was possible to hear what was playing in the background. At that moment it was Surfin’ Bird. ‘Well, everyone’s heard that the bird is the word. Bird, bird, bird. Bird is the word…’

‘Thank you,’ said Katya. ‘I’m glad you went.’

Paul was still wrapped in the duvet, his head sunk into one of the pillows. He opened an eye and saw her leaning over him.

‘You are awake, aren’t you?’

‘Vaguely.’

‘How do you feel?’

‘Vague.’

‘Need a Tylenol? Glass of water?’

‘Mmmm… Undetermined.’

‘Do you want me to do breakfast? I can…’

‘No,’ said Paul. ‘I’ll do it. Incentive’s probably a good thing. I expect.’ And with that he propped himself up and looked around the room.

‘You know,’ he said. ‘We could probably get rid of some of this stuff.’

Katya looked around the room trying to see what he was seeing. The room was by no means cluttered, but it was rarely a bad thing to simply agree with him. If it was unimportant, as it was here, he’d usually forget anyway.

Paul swung himself over the edge of the bed, his hair flat on one side, sticking up on the other.

‘How are you?’ he asked.

Katya shrugged.

‘Sleep okay?’

Again, she shrugged.

Since falling down the steps, Katya’s nights had been painful affairs, long and often sleepless. She’d dislocated one hip, done a number on one of her knees and suffered a mild concussion. It was hard to see this as having been lucky, but having now proclaimed exactly this over the phone any number of times it was difficult not to accept that things could have been much worse.

‘Was it fun?’ she asked him. ‘Did you enjoy yourself?’

‘Fun? Well… There was certainly lots of wine. Every time I looked someone had topped up my glass.’

‘Poor you…’

‘Hetty’s gone and bought all these tapestries. Put them up in the dining room. It felt crowded.’

‘That’s interesting.’

‘Reminded me of my mom’s stuff.’

‘Who was there? Tell all, you. Divulge. This is why I sent you. I need life,’ she said, smiling with mock malevolence, ‘Understand?’

Paul told her the bits he could remember, that Oscar was there, about Candice, and a quarter of an hour later he was still talking as they emerged from the bedroom and made their way down to the kitchen, Katya taking the steps one at a time, clutching the banister.

They could hear voices, and Paul turned to Katya questioningly, before remembering that Evelyn had asked to have a friend over the night before.

‘Oh,’ groaned Paul. ‘Monique.’

‘Now, now.’

‘She’s a vegan, isn’t she?’ he whispered.

‘Vegetarian,’ cooed Katya. ‘She’ll eat eggs. I asked.’

The two girls were seated at the kitchen counter, and whatever they were talking about it stopped the moment the parents entered the room.

‘Good morning,’ said Katya, good-naturedly. Paul said nothing and would not even look at Monique. He began rooting around in the fridge.

‘Morning daddy,’ said Evelyn. Paul peeked round the fridge door and smiled, but not convincingly.

‘Are you making one of your egg thingys, dad?’

‘Yes,’ said Paul. ‘It’ll probably be about… well, almost half an hour.’

And it was. Half an hour later the four of them sat at the kitchen table eating something that resembled an egg pizza, Monique saying three or four times that it was delicious, but that her brother would never eat it. For the most part Paul hid his bleary self behind the Globe and Mail. If asked what it was he most disliked about Monique, he likely would have been some time before seeing how much she resembled him at that age: out-spoken, self-centred and precocious.

Two hours later he was driving her home, the two girls in the back seat as if he was their chauffeur. Normally it wouldn’t have mattered, but today for some reason, perhaps because it was Monique, perhaps because of lingering feelings of vagueness, perhaps because of something he couldn’t put his finger on, it bothered him. He felt used.

They waited in the driveway to see Monique safely in, then Evelyn climbed over the seat and sat up front. Backing out, Paul muttered something about why does everyone have to live so far away.

‘It’s a testament to our friendship,’ she said.

Paul might have guessed she’d be able to argue the point.

On the way home he was in a dark mood.

Half-way there he turned onto a street that was unfamiliar to Evelyn. For several blocks she had no idea where they were going, and even when they arrived she wasn’t sure what they were doing there.

‘Daddy?’

He flung open his door, saying, ‘We’ll just be a few minutes.’

Evelyn climbed out and the two of them passed through the gate into the cemetery.

Hers was not a headstone. He and his sisters had gone for a simple marker set in the earth.

‘Do you remember her?’ he asked.

‘A little.’

‘The day we came here to put the ashes in, we were all standing around here saying a few things, we were quiet mostly, and you and your cousin were fooling around over there, playing hide and seek in the tombstones. And your mother said how much my mother would have liked that. And she would have. That was her.’

A moment later he said, ‘Don’t worry. We’ll go soon.’

Quietly, she put her hand in his.

From there they went down by the water, down to the beach. They kicked off their shoes and carried them, and bought ice cream from a cart and walked over to where there were some stones they could throw in the lake. And they ate their ice creams and skipped stones over the tiny waves, and Paul was just saying to Evelyn how if he was a good father, if he was to do the right thing by her, he ought to take her home and show her how to clean a kitchen floor, because there were few things in life that felt better to be done with. He was just saying that when a photographer took their picture and asked if they’d mind if it appeared in the newspaper next day. And neither of them, so they said, neither of them minded.