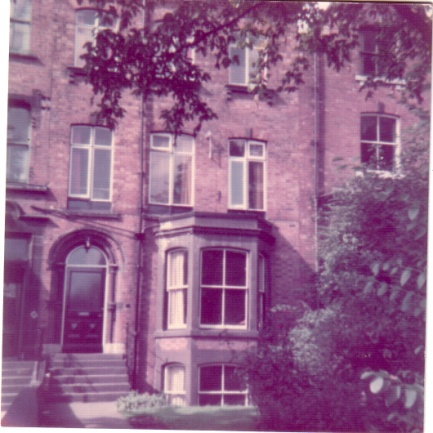

Orange: blue’s complementary colour, and absolutely banned by my CMB adviser in Sheffield. Nevertheless, it inserts itself here as something to be confronted, representing a memory as uncongenial to me as the colour itself. Early 1979 – I’m not sure of the exact date. By then, there were only three of us still living in the collective house in Leeds after the break-up, during my three-month absence in the U.S. the previous autumn. Complicated personal relations, sexual politics, and other problems I was kept informed about – I assume it must have been by letter, since there was no email then and I don’t recall many phone calls. It was a large, four-storey terraced house, five minutes from the university where three of us worked, and still ‘inner city’ enough to have been very affordable (£10,000, as I recall) in 1975. Most recently it had been used as a children’s home, and perhaps because of that there was a bathroom on three of its four floors. The lower ground floor comprised a living room and a large kitchen/dining room, with a door out to the small garden at the back. We spent most of our time, together with many visiting friends, round the table in that room. But now the house would soon be sold and we would each be living somewhere else. Before that, though, was orange – in the form of a line of washing hanging one morning in the basement kitchen/dining room, announcing our house-mate’s expected decision that she had joined the Bhagwan. A shared domestic life – five adults and two children – begun four years earlier, tailed off rather pathetically at that point. As for the colour – the new sannyasin, who left for India soon after the washing episode, wrote in her 2007 memoir:

Someone once asked Bhagwan why we had to wear orange. He explained it was the traditional colour for sannyas, the colour of sunrise signalling the dawning of a new age. But I think it was to mark us out, to force us into each other’s arms, as who else would willingly walk down the street next to someone swathed in such a deadly colour.

All this is now more than thirty years ago, and no doubt none of us remembers the details. Still, coming across a memory which bears little relation to my own has something of a shock effect. In the same book, she writes about the time, a couple of years earlier, when she had come to live in our house:

I applied to join a neo-Marxist socialist-feminist commune. After an interview where I wore my badges of revolutionary slogans, dropped in the names of my most right-on mates, mentioned the conferences I’d attended, the barricades I’d fought at, I was in.

Applied? Interview? Political requirements? And four people (one had recently left) as a ‘neo-Marxist socialist-feminist commune’? We were really just a group of friends, with no particular shared political activities – two men, two women, some of us colleagues, two with kids who lived half the week with us and half with their fathers, nearby. The account has no connection at all with my memory of our household.

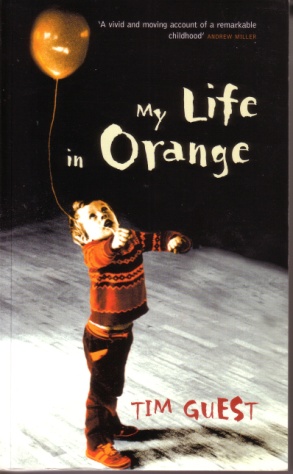

And I also try to square my memory of the orange-dyeing moment with that of her son, then aged three, who lived with us part of each week. His name was Tim Guest (Timmy in those days), and many years later he wrote a wonderful and moving book, My Life in Orange, about his early years in the Bhagwan’s communes in India, England and the U.S.

Three weeks after hearing his voice on tape, my mother posted her letter to Bhagwan. That afternoon, upstairs playing with my Lego, I heard a loud splash. I went down to investigate. My mother was in our bathroom, her arms stained orange up to the elbows, sloshing all her clothes around in the bath, which was filled to the brim with warm water and orange dye. Later that evening she wrung her clothes out and hung them by the fire – to my delight, they left permanent orange stains on the fireguards – and from then on, she wore only orange.

An old friend from the Leeds days got in touch in 2004, to tell me that ‘Timmy’ had written a book which was getting a lot of publicity. That is how I found out that he had become a journalist and writer. Although I only lived with him and his mother for a couple of years, and haven’t seen either of them since 1980, I read the book with great interest and have re-read it several times since. It is a beautiful, generous, heart-breaking story, an account of the disasters of communal life based on a strange (and later discredited) spiritualism, sexual freedom, and chaotic disorder for the children involved. John Lahr, the New Yorker critic, called it one of the best autobiographies of the decade. Elaine Showalter, reviewing the book in The Guardian, says that this ‘calm, meditative, and even lyrical memoir is a testament to his recovery’. Certainly he became a very successful writer. The particular memory doesn’t fit though. For one thing, he and his mother had a bedroom each and a bathroom they shared all on one floor, so he wouldn’t have gone down to investigate. Also, we didn’t have open fires anywhere in the house, so I can’t see how there could have been fireguards. Of course it doesn’t matter. But I hoped to get in touch one day, and compare memories. This didn’t ever happen.

Tim Guest’s second book, Second Lives, was published in 2007. It is an ethnographic study (if that’s not a contradiction) of virtual communities and of the entrepreneurs who created those worlds, and it too was very well received by critics and readers. Later, some noticed the continuities between the two books, the recurring damage, perhaps the impossibility of full recovery. Guest himself (it seems a little strange not to call him Tim) hints at it, without making this a big deal in the book – indeed, only on page 246, though he alludes to the connection briefly throughout:

When I was four, my mother and I moved into the communes of her guru – a bearded man-god who promised ecstasy and delivered mainly absence. I was supposed to be the child of the commune, not of my mother…. In the communes that bore Bhagwan’s name, she and her friends danced, rolled their heads, swayed their arms, beat cushions, broke down their social conditioning and set themselves free. Meanwhile, we children filled our lives as best we could with the things we found around us.

I filled the space with my imagination… By chance, I had uncovered the purpose of the imagination: to conquer absence. Our dreams give us a lens through which to examine what we lack – just as virtual worlds do.

In 2004, he wrote a short personal essay for The New York Times magazine about his fear of commitment, his desire to marry and his deep resistance to taking this step and particularly to having children. His girlfriend of five years is keen for them to buy a house, and she wants to start a family. He knows that his resistance has everything to do with his own suffering as a child of the Bhagwan’s communes, and some sort of fear that his own children might suffer. He ends on a tentatively optimistic note, deciding to go ahead with the house and to try to leave his childhood behind: ‘Maybe it’s time to let go of my grievances, to grow up, to give some new little person a chance to be young.’ In fact he got married in October 2008, to a woman he met at the Notting Hill carnival in 2006. Ten months after the wedding, his new wife found him dead in bed, at the age of 34. The first obituaries reported an unexplained death, with suggestions that the cause was a heart attack or a stroke. In an essay in The Observer in March the following year, Elizabeth Day tells the full story – of his early life, his recovery through writing, his periods of drink and drug-taking, and his eventual marriage. He died of an overdose of morphine. Day speaks to his family and friends and his wife Jo, and concludes that although this was almost certainly not a suicide ‘it seemed none the less as if his commune experience had cast a long shadow and he was never entirely sure whether to embrace its legacy or try to escape it’.

I am touched by the fact that this lovely writer (and, by all accounts, lovely person) has a connection, before his troubles really began, with a moment in my own life. The moment before orange.