I corresponded with Colette in the summer and autumn months of 2018, amid the publication of her Selected Poems. She was based in Newcastle-Upon-Tyne at the time, and our emails covered many of the highlights from her distinguished publishing career.

Bryce is Derry-born and was a recipient of the Eric Gregory Award. Her poetry has been described in The Guardian as ‘precise, her word play sensuous, smart and snappy.’ Her work first came to my attention with her poem, ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’ which won the National Poetry Competition in 2003 and went on to become the title of her second collection, published by Picador, 2004; short-listed for the TS Eliot prize.

What I like about Bryce’s work is its ability to fuse strange and surprising scenarios with immediacy and clarity. Her forensic and singular gaze, the unfussy syntax and subtle lyricism, gives space for her stirring anecdotes and often haunting metaphors on modern life and our inner-lives. On the back of the recent publication of her Selected Poems, I took the opportunity to ask her questions on her compilation process, as well as delving deeper into poetry-making and preoccupations. As it is a time of Irish centenaries, I also asked Colette about her relationship with Ireland, her personal experience of growing up in Northern Ireland and how this may have influenced her work.

Colette Bryce

Adam Wyeth: Your Selected Poems was published in 2017. What was this selection process like? Was it a simple exercise of choosing certain poems that stood the test of time and losing some old darlings, or was it difficult to know which poems not to include?

Colette Bryce: The selection process involved travelling back as a reader and seeing if the poems still held their own. It’s like meeting one’s younger selves in an elevator, quite unnerving. You know, to paraphrase Lou Reed, they’re still doing things that you gave up years ago. Poetry is a long process, not always linear, sometimes circling back, but we’re forever striving onwards to the next poem. That’s the exciting thing, the realm of possibility. So I found myself reluctant to go back and scrutinize my previous work in this way. I knew I would have to find a degree of objectivity, and try not to interfere belatedly. I don’t know if it’s the same for other poets, but I’m a good deal more critical when it comes to my own work.

Later, meeting with my editor, some of the conversation was about what to put back in, to allow the earlier work fair representation. I hadn’t reached a point where I felt a need to compile a Selected, but once my publisher had suggested it, I found the process helpful as a way of taking stock. It turned out to be a good experience, a growing experience. I could see lines of connection that I hadn’t paused to consider before.

Generally speaking, a kind of reduction is natural for me, being an inveterate editor. Trying to get the poem down to its essentials. Selected Poems is perhaps a bigger book than I might have created naturally, left to my own devices. Running the poems together as one book, one collection, was pleasing – I wanted that continuity, unity, rather than sections representing individual books. There’s an old theory that some poets are really writing the one book, published in instalments. Each collection is important to you, of course, but the ongoing process much more so.

AW: Gerry Murphy called his recently published Selected Poems, End of Part 1. Which seems an apt title for a first Selected book. How do you think you’ve changed as a poet since the Colette Bryce of her first or second collection? Have your core concerns and/or aesthetic sensibility remained intact?

CB: It’s quite hard to answer that about yourself. The poetry is inseparable from the life, and we all bear the dents of experience. I write out of experience, a kind of translation. Poems I suppose might represent ‘selected’ experience. They’re all pinned to the pilgrim progress.

The virtuous obscurity in which some poets work (that Oscar Wilde considered ‘anything better than’) is probably helpful in retaining a core sensibility. The writing remains an intensely private process. For that reason I’m always wary of laying down firm opinions about poetry. The more I know, the less I know. There’s a private place of unknowing that is connected to the impulse. An artistic innocence, perhaps.

AW: 2018 was the 20th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement and the Omagh bombing. Northern Ireland, language, and politics run parallel in your work. I wonder how much of an effect Northern Ireland has had on your poetry? Do you think Ireland has played any part in you coming to poetry in the first place?

CB: When I left Northern Ireland, becoming a poet was about as imaginable to me as becoming an astronaut. I had never heard of a living woman poet, although I was an avid reader of women’s fiction. Somehow, female poets had not been admitted into the culture I was exposed to, or to my education. A friend’s mother had a library of Virago and Women’s Press fiction titles that were a revelation to me, and the first steps in my feminist consciousness. Yet, in my limited experience, there was no model for poetry. And there were Irish women poets writing great work back then, but I didn’t know about them. That came later. The importance of role models can’t be underestimated.

The impulse to write was there, but counteracted by a strong resistance. I had grown up in a culture of secrecy, so in some ways writing always felt like a rebellion against this, and it took time, distance and courage to begin to write. Writing can seem incredibly exposing, whereas I’m a naturally private person. It was only after my degree, when I started discovering younger contemporary poets, that I found a sense of connection and permission. For the first time, I could read of women’s lives and urban and working-class experience in poetry, and that was enormously energising. In fact, it was life-changing.

But getting back to the present moment, and the anniversaries. The poetry of Northern Ireland – of Ireland as a whole, actually – has provided an alternative way of thinking about those years and events. I am steeped in that poetry, and I’m fascinated always by how my predecessors, peers, and the next generation, add their voices to the range of perspectives. For me, the war there, or conflict, or Troubles, or whatever we choose to call it, was my ordinary lived experience as a child and teenager. My writing about that time comes from a fairly direct perspective. I was involved in the activism in my community from a young age, and we were fired up about the issues. The Bloody Sunday justice marches, anti-internment, the Hunger Strikes, with all their attendant demonstrations. Politics was in the warp and weft of the everyday, and my context was a Catholic, republican community with a history of oppression. There was great energy for change, as the recent anniversary of the civil rights movement reminds us. There’s a phrase in my poem ‘Heritance’ – ‘an historical anger’ – that I associate with my mother. I always sensed it was not the done thing to write from that perspective. There’s a nervousness around it, for obvious reasons.

AW: In an essay of yours from 2014, you refer to a Heaney essay where he talks about the word, ‘Omphalos,’ the Greek term for the centre of things, which conjured up for him the pump in his childhood yard. For you, however, this word called to mind the helicopters hovering over Derry… You write how, ‘The blades are related to words, in opposition to our words, slicing up sentences in the wind.’ This violence of having one’s words and/or even a tongue sliced up is a powerful and memorable image. Do the slicing blades refer more to other people’s sentences, or to your own?

Both, I think. There’s an image in my poem ‘Derry’ of Gerry Adam’s mouth moving on the BBC news, only dubbed by an actor. I can remember seeing the tiny, tightly-wrapped letters that were smuggled out of the prisons via kisses. Illegal words. And there was the pervasive culture of nervous reticence summed up in Heaney’s poem ‘Whatever you say, say nothing’- ‘the tight gag of place and times’. The helicopters drowning out speeches is a clear memory I have from demonstrations at Free Derry Corner, and also at political funerals/memorials. Words were dangerous. The Don’t Speak directive became a noticeable thread in my last book. In my recent poems, I see it weaving in again –phrases like ‘don’t say any of this’, or an image of the ‘stitched mouth of censorship’. I’m interested in both repression and suppression, the unconscious censoring of experience, and then the willed or sometimes externally imposed censorship, in the public and in the private sphere.

I remember in my twenties, when I was reading everything I could get my hands on, discovering the American poet Sharon Olds. Her first slim volume, Satan Says, had a powerful effect on me. The drama of the opening poem, where the speaker is trying to write her way out of a box, prompted by Satan. And other American women poets like Muriel Rukeyser and Audre Lorde, queer and political writers, were exciting to read. Closer to home, a new generation of poets in the UK where I lived were responding to Thatcherism and social issues. Speaking out, in creative ways. I admired poets with a bit of nerve.

Poetry is at its essence ‘memorable speech’. When we work away for weeks on a short lyric, we’re taking a long time trying to say something well. I’m fascinated by the extent to which the written word is splurged out in our contemporary moment on social media, an incessant river of randomness. To publish one’s thoughts as they occur seems amazing to me. Like the opposite of poetry. I was brought up with a cultural respect for the written word; to commit something to writing was a telling phrase – there was a degree of commitment.

Do you have a poem of yours that best sums up your experience of growing up during the Troubles?

Gosh no. But a few might speak to me of that experience in unusual ways. ‘A Spider’, for example, can I hope be related to anyone’s experience of being trapped. ‘Don’t Speak to the Brits…’ is a more playful take on the cultural confusion of our life on the border, and the suppression of speech I mentioned before. The ballad-like poem ‘Derry’ sought to tell a story of sorts about that experience. In its narrative directness, it’s unlike other poems in the Whole and Rain-domed Universe, which circle around that place more than in any other book. An earlier poem ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’ holds something of the vanishing point of emigration, a rite of passage that seemed so inevitable then.

I should probably say that I never consciously intended to write ‘about’ Northern Ireland. There was a sense in which that place and time had been endlessly processed in the language of journalism. But I’m very much at the mercy of where the poems lead. In my early 40s, I noticed that quite a few poems were conjuring that place and time, perhaps it’s a time of life thing. When I began to assemble the collection, I was surprised to find how they fitted together. My new work, on the other hand, is not about the place at all. The recent poems are concerned with other matters.

Hiddenness and disappearance are recurring themes in your work. How much is this a conscious element in your poetry? Dennis O’Driscoll thought that each poet has a particular word that is particular to them. Would it be fair to say that your particular word might be ‘hiddenness’ or ‘disappearing’, or is it something closer to transcendence perhaps?

It’s funny you ask that, as I have the manuscript of a new collection lying on my desk and I had already noticed that the last word is ‘disappear’. I’ve become more aware of mortality recently, as I lost two close family members in the last year. The new poems are striving to think through the reality, and the attendant sense of unreality it brings.

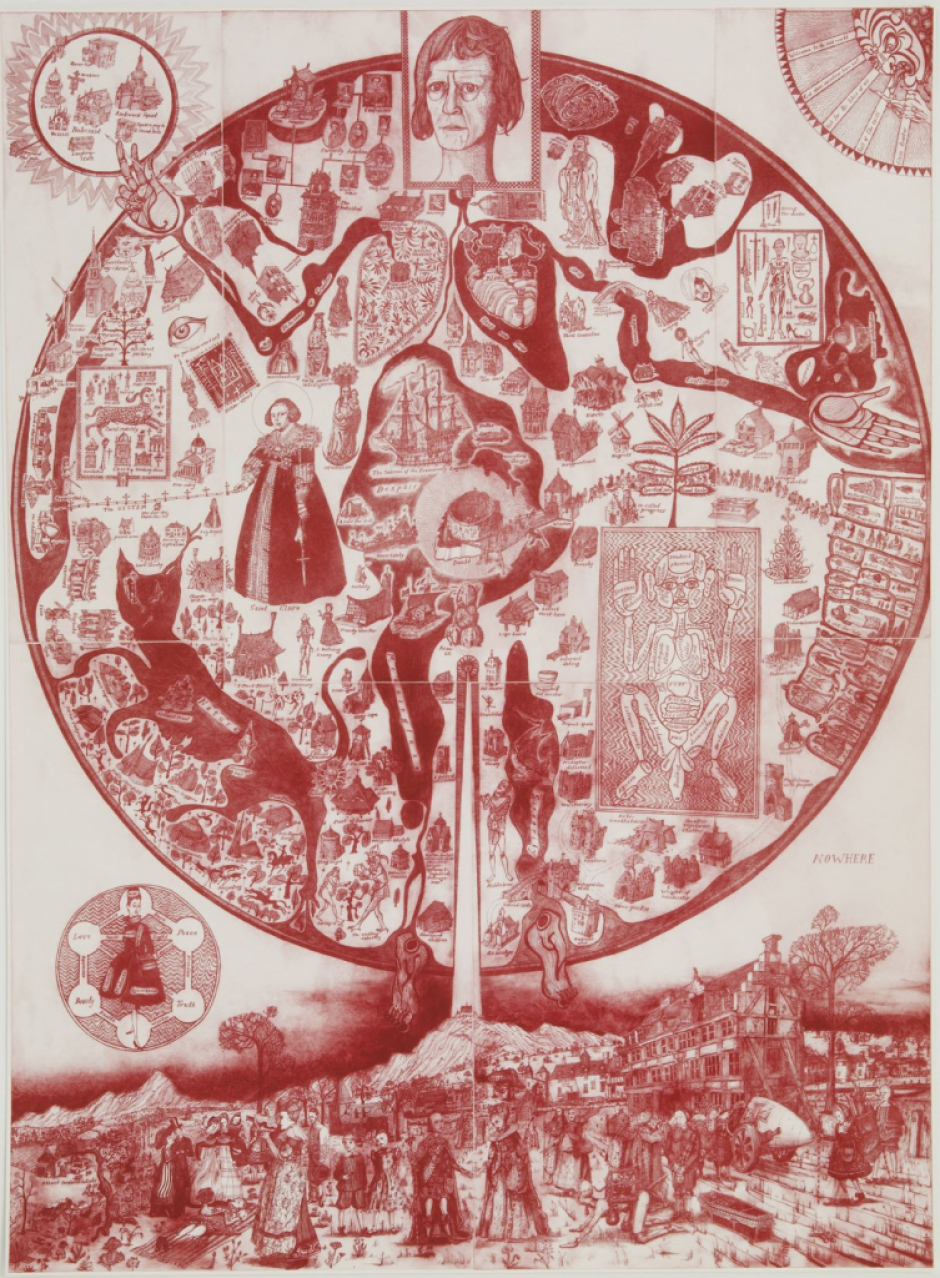

In terms of a word or concept, I think sometimes of outsiderness. Various layers of outsiderness that come from the emigrant experience and also being gay in a predominantly heterosexual cultural context. From working for a long time in a solitary discipline. Of being categorised a British writer in one place, an Irish writer somewhere else, sometimes neither, and you’re simply not there. I’ve often felt at a remove. But I’m aware too it can be an interesting (no)place to write from.

The etymology of the word poet in English is ‘to make’ whereas in Irish it’s file, ‘to see’. Your poetry is all about keen observation. Your meditation poems on creatures for example, such as lobsters, crabs, spiders become complex metaphors often revealing aspects of our own inner-lives. Virginia Woolf, one of the great observers of English Literature, in her essay The Death of the Moth ekes out a world of details from this tiny, seemingly insignificant creature. Are noticing the small things of our world, something you are drawn to as a poet?

I’m a great admirer of Elizabeth Bishop, who probably exemplifies that close observation you refer to. There are times when the act of close description can lead you into a subject and the poem emerges out of it, in an unexpected way. It’s good practice, I think, like sketching for a painter or sculptor. The image is the fruit of this endeavour, the simile, the metaphor. What is it like? Connection and connection. As a young poet, I was charmed to learn that the Greek work Metaphor means literally a carrying over, and there is a variety of transport vehicle in Greece with the brand ‘Metaphor’ across the bumper.

‘To make’ seems closer to my experience of poetry. Which brings me back to the pleasure of process. Derek Mahon refers, in his new book, to the ‘trance of composition’. That’s the happy place, of making and tinkering. Hours disappear.

The musicality of poetry comes across as a powerful element in your work. What comes to you first when you are composing a poem, is it music or meaning, or are the two inseparable?

The essential task, and sometimes the greatest difficulty, is to reconcile the patterns of sound and sense as much as one can. The nucleus of a poem is often a single image, and then a spidering out from that with pen on paper. The poem begins to gather itself. In my poems, I have always sought to communicate directly on one level, to create a speaking voice where the reader feels addressed and included. I genuinely wish to communicate, to bridge across to the experience of another person. And yet, poetry is close to song for me, there is a musical tension to be attended to, in which the poetic line, and line break, is key. Thom Gunn once observed how metrical poetry is ultimately allied to song, and free verse to conversation, and how he liked both connections. I do too, and an apparently free form poem is often a delicate negotiation between the two. Poetry is always working on the reader in that aural and rhythmical way, beyond what the words are saying. When these two things are in harmony, we’re in business.

You’ve spoken how you write formally for the ear more than for the eye. Yet you often approach line endings and punctuation in a very particular way. How important is the look of the poem on the page for you?

Well, it’s extremely important. I’m drawn to pattern, symmetry, and the fruitful interaction with the white space, the silence around and within the poem. Some poets like to memorise their poems and recite them ‘hands-free’, so to speak. For me, the page is very much involved. I like to read my work with the book in hand, my eye still interacting with the visual of the written poem.

How important is the blank space, or the ‘frosted glass’ around your poems for you?

It’s a key element, the way in which the words interact with, or come up against, the representational silence. It’s where the music happens. And in meaning, yes, sometimes omission is the right choice. My last book, The Whole & Rain-domed Universe, begins with ‘a dream of white’, the lure of passivity and silence. And it closes with a reinstatement of ‘each white space’ in a crossword grid, alluding to the retreat of language in (my mother’s) old age.

You’ve lived in England for many years now and have spoken about how emigration has been a central and continual experience in your life, and this perhaps is reflected in your work where people leave or even disappear, such as the speaker in ‘The Full Indian Rope Trick’. In the wake of the Brexit referendum, we hear stories of people who are leaving the UK because they feel unwelcome or insecure there. How does the referendum result affect you, and has it ignited anything in your poetry?

It’s clarified my desire to move back to Ireland. I value Irish literary culture more and more, as a kind of deceitful populism becomes the norm in the UK. But at my (advancing) age, you start to appreciate the long view. Poets have always worked away quietly on the margins, and I like that. You get very little response. It takes resilience to keep going, and a faith in the process. Geographically, I’ve always felt homeless in my adult life. A novelist recently described the feeling well, describing her location as ‘the city in which I don’t feel I live, but in which I have actually lived for twelve years’. That resonated with my experience. I travel a lot these days, which I love, including to Ireland often. I feel oddly at home in transit.