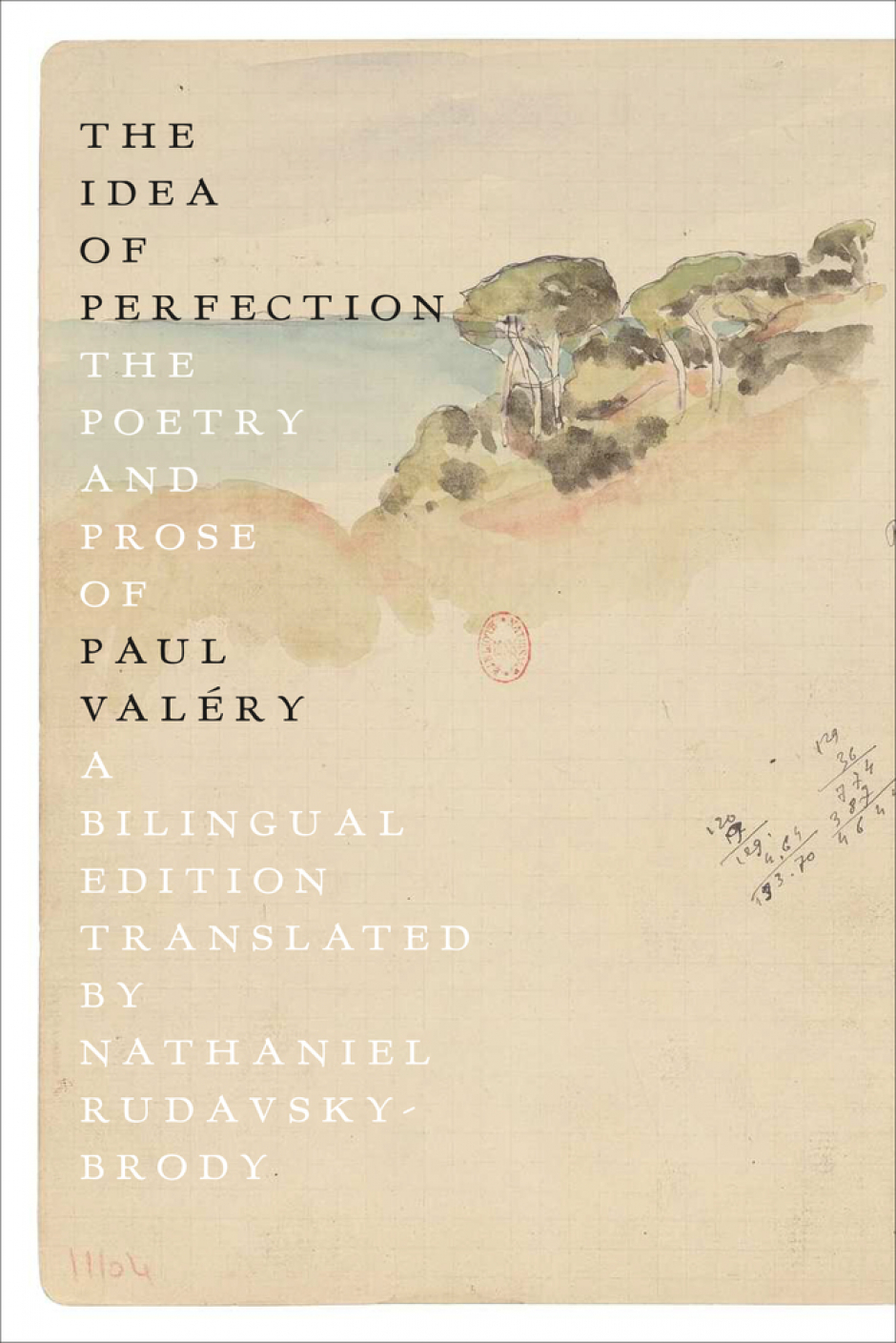

Paul Valéry, Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody (translator)¦The Idea of Perfection The Poetry and Prose of Paul Valéry: a Bilingual Edition¦Farrar, Straus and Giroux hardback $54.50¦ reviewed by Edmund Prestwich

Paul Valéry, Nathaniel Rudavsky-Brody (translator)¦The Idea of Perfection The Poetry and Prose of Paul Valéry: a Bilingual Edition¦Farrar, Straus and Giroux hardback $54.50¦ reviewed by Edmund Prestwich

Paul Valéry occupies an ambiguous position in modern literary culture. In later life – after he’d stopped writing poetry – he bestrode the French cultural scene like a colossus. The American poet and critic Yvor Winters called ‘Le cimetière marin’ and Ébauche d’un serpent’ ‘the two greatest short poems ever written’. For T. S. Eliot, too, he was a giant. But I don’t think he’s read much in England now, except in specialist academic circles.

His relatively slender output in verse consists essentially of three collections, the Album de vers anciens, 1890 – 1900 (largely written between 1890 and 1892 but published in 1920, apparently with extensive revision), La Jeune Parque, published in 1918, and Charmes, published in 1921. The Idea of Perfection presents the French texts in parallel with Rudavsky-Brody’s English translation, interspersing selections from the poet’s voluminous notebooks, in translation only. Rudavsky-Brody’s introduction sets the work in biographical and literary context, discussing Valéry’s relation to the Symbolists, especially Mallarmé, and sketching out his extraordinary, even paradoxical poetic and intellectual ambitions.

The passages from the notebooks were a revelation. I think the only bits of Valèry’s prose that I’ve read before were famous quotations about literature in general and poetry in particular. Valéry the thinker and Valéry the extremely self-aware observer of his own mental processes are here, of course, but what I’ve learned is that he also had spectacular gifts for observation and vivid, concrete description of the physical world around him. One paragraph will have to stand for many electrifying pages in which these different aspects intertwine:

Caught in the rain today, I recall that couple kissing and holding each other infinitely close in the rain one dark evening under the nearly invisible trees, in the Allée de l’Observatoire. I remember speaking with Pierre Louÿs of the impression which that man and woman made on me, so unexpected, silent, clasped in their arms and so completely alone together on their dripping bench that they made me doubt the thunderous rushing downpour. For them, neither rain nor me.

The poetry raises more complex issues. In his 1931 study Axel’s Castle, the great twentieth century American critic Edmund Wilson wrote, ‘there has perhaps never been a poet who enjoyed the sensuous world with more gusto than Valéry or who more solidly bodied it forth. In the reproduction, in beautiful verses, of shapes, sounds, effects of light and shadow, substances of fruit or flesh, Valéry has never been surpassed.’ I agree. Sometimes, however, enjoyment of that aspect of his genius is complicated by intellectual frustration. La Jeune Parque or The Young Fate, a poem of over 500 lines, is notoriously difficult to grasp as a whole, sliding as it does between sensuousness and eroticism in its imagery and extreme abstraction in its apparent thought, presenting a kaleidoscope of shifting interpretative possibilities without a clear narrative or conceptual frame that will help the reader get them into focus. In Charmes, there’s a similar straining between concreteness and abstraction in the long and incomplete ‘Fragments du Narcisse’ or ‘Fragments of “Narcissus”’, though here again particular passages of sensuous description give me keen pleasure. That said, for me and I think probably for most new readers the easiest entry to Valéry’s poetry is through the short and medium length poems of Charmes, especially in French. The great ‘Le cimetière marin’ (‘The Cemetery By the Sea’) is widely known, whether in French or in English. This poem is both wonderfully grounded in a physical and dramatic context – that of the poet meditating in a cemetery by the sea – and wonderfully sensitive in its tracing of the elusive movements of a mind confronting the limits of where the mind can go. Other poems, less robustly grounded, will perhaps seem mere elegant trifles to some readers; to others they’ll seem as enchanting as the volume title suggests they should. Their meanings are often elusive, not so much puzzling as hard to pin down very definitely, working as they do through suggestion rather than statement and lending themselves to different levels of interpretation, often set in motion by the gentlest of hints. To me, such a hovering between meanings is a pleasure in itself, in the context of a short poem, and given the remarkable clarity of form and verbal grace of Valéry’s writing.

Admittedly, if you don’t read French enough to read the originals, perhaps with the support of the translations and a dictionary, much of this beauty will be lost on you. The special problems inherent in the translation of poetry become particularly acute in the case of a poet like Valéry for whom the formal qualities of poetry were crucial determinants of content. Rudavsky-Brody’s Introduction quotes Valéry’s famous definition of the poem as ‘that prolonged hesitation between sound and meaning’. Another much-quoted statement, ‘A poet’s work consists less in seeking words for his ideas than in seeking ideas for his words and predominant rhythms’, makes the point even more clearly.

We can see different kinds of loss in translation by looking at the first stanzas of two sonnets. First, sound patterning and movement. In the first stanza of ‘L’abeille’ Valéry writes

Quelle, et si fine, et si mortelle,

Que soit ta pointe, blonde abeille,

Je n’ai, sur ma tendre corbeille,

Jeté qu’un songe de dentelle.

Rudavsky-Brody translates this

However keen may be your sting,

However fatal, golden bee,

I’ve spread across my tender basket

Only the merest dream of lace.

Rudavsky-Brody’s brisk pace gives a quite different feeling to the deliberate, step by step way in which Valéry’s poem advances across a series of pauses for qualification and emphasis, and he loses Valéry’s extremely rich sound patterning. This matters because the pattern itself is crucial to Valéry’s effect. The solid core of the stanza, and of the sonnet as a whole, is not what it says but the shapeliness of its metrical and stanzaic structure and the gracefully intricate unfolding of its sound. Meaning is an elaborate but elusive shimmering of suggestions around this core – a shimmering in which all the possible meanings, metaphorical suggestions and associations of the words used have their place.

The first stanza of ‘La ceinture’ illustrates a different problem, this time to do with the play of suggestions itself:

Quand le ciel couleur d’une joue

Laisse enfin les yeux le chérir

Et qu’au point doré de périr

Dans les roses le temps se joue

Rudavsky-Brody gives

When blushing like a cheek, the sky

At last admits the reverent eyes,

And tipping toward a golden death

Time plays a while among the roses

Here, the problem is how to translate ‘les roses’ and ‘le temps’. In French, ‘les roses’ can refer to both different shades of the colour pink and rose bushes. Both meanings are important. The first develops the tender radiance of that sunset sky that has been metaphorically evoked in the first line. The second adds overtones of the erotic associations of roses in poetry, the soft skin of rose petals and roses’ fragrant smell, which is like the perfume of the girl whose cheek is compared to the blushing sky. In English you have to go for one or the other. In French all these different meanings and associations radiate out of the same word, and that’s how Valéry’s poetry works. The problem with ‘le temps’ is essentially similar – in English you have to choose between translating this as ‘time’ or ‘the weather’, but the scene Valéry imagines is made up of both a time of day and the weather conditions at that time. We tend to think of English poetry as tending towards the concrete and French towards the abstract, but here the reverse is true.

However, the reader who can only read Valéry in English will find a great deal to enjoy in Rudavsky-Brody’s translations, and a fascinating introduction to a major poet in his selection of work. To finish, here’s his version of ‘Les pas’ – ‘The Steps’. On one level, this is a rich and tender love poem in which the poet waits while his lover approaches but it’s also often given an allegorical interpretation as a poem about inspiration:

Your steps, the children of my silence,

Saintly, calmly approach the bed

Of my long waiting, with their stilled

And measured fall on the cold floor.

How soft and how discreetly sound

Your steps, pure being, sublime shade!

O Gods… What promises of gifts

Draw close at last on your bare feet!

Yet if on your advancing lips

You would prepare, to pacify

The thought-entangled dweller of

My mind, the sustenance of a kiss,

Don’t rush that act of tenderness,

Sweetness of being and not being,

For I have lived in expectation,

My beating heart became your steps.