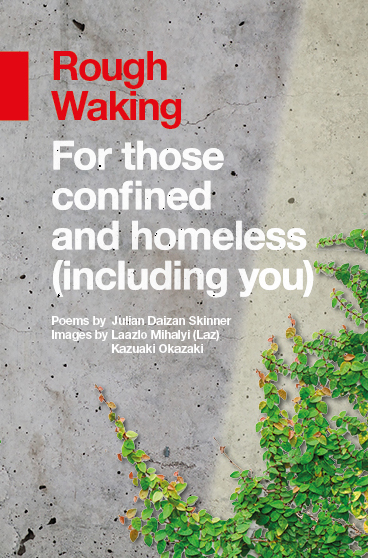

Julian Daizan Skinner, Laszlo Mihaly, Kazuaki Okazaki | Rough Waking | Zenways Press: £12.99

Rough Waking combines visual imagery and poetry in an exploration of the apparently paradoxical themes of homelessness and confinement; or confinement-in-homelessness and homelessness-in-confinement. The book is divided into three sections, and the contributors are Laszlo Mihaly, a photographer who spent many years living on the streets of London; Kazuaki Okazaki, who was executed last year in Japan after spending 18 years in prison, and Julian Daizan Skinner, the first Englishman to become a Zen master in the Rinzai tradition.

Laszlo Mihaly was released from confinement in a secure mental hospital to discover that he had lost everything, wife, home, possessions. While living on the streets he managed to establish a meditation practice in 2014 that helped him to cope with his bipolar disorder. Also he began to record his experience of homelessness in photographs. These photographs and reflections constitute the first part of Rough Waking. Sensitive, eloquent and wholly without sentiment, they capture both the deprivation of life on the streets and the possibility of grace.

As a young novice, Skinner experienced the constraint of a monastery in which the meditation hall served as both eating and sleeping quarters and each inhabitant was allocated a living space measuring three feet by six. He lived in this way for seven years, and later experienced homelessness in terms of the walking pilgrimage, – up to 1000 miles without money or shelter; nothing in fact apart from his monkish robes. When he returned to England, in 2007, he encountered homelessness again, undertaking to walk from the Isle of Wight to the far north of Scotland with no money, accepting only what he was offered in terms of food. Daizan Skinner is a published poet and his poems here reflect on his own spiritual journey, moving between confinement, homelessness and liberation.

Time to re-enter the valley.

I flap down through the wind

lonely

As a solitary crow

Autumn in the Monastery and Other Poems, constitutes the 2nd part of this book.

Daizan Skinner’s Japanese master, Shinzan Miyamae, visited Okazaki in prison at the latter’s request, and began training him in Zen. In order to do this, he adopted Okazaki as his son, because once consigned to Death Row in Japan, a prisoner can only be visited by close family. During his training, Okazaki produced a series of ink drawings entitled Release – Unsui’s Journey. ‘Unsui’ is the term for a novice Zen monk, someone who ‘wanders freely over the earth like clouds, like water, seeking an entrance to the truth’. The drawings depict a spiritual journey, from confinement to boundlessness, ‘a deeper, cosmic dimension of homelessness.’ They constitute the third part of Rough Waking.

But the subtitle of this book is for those confined and homeless (including you). The message is that we are all suffering from a similar paradox of confinement and homelessness. Like Adam and Eve, cast out of the Garden of Eden into a wilderness of uncertainty, deprivation and toil, we are caught up in ‘incompatible dreams of security and freedom.’ The implied reader of this book suffers from alienation and estrangement; the sense of not belonging and the sense of restriction that, it is suggested, is the human condition.

Rough Waking moves between the particular and universal, or archetypal, in structure as well as theme. By juxtaposing photographs of homeless people with poems exploring the monastic experience and spiritual journey of a monk, and with artwork representing the transcendence of suffering and confinement, Rough Waking creates a particular kind of resonance between these elements.

One way to describe these apparently disparate elements in a productive and reciprocal relationship is with the philosophy of abiding usually found in Christian theology. Dr. Andrew Brower Latz has written about the philosophy of abiding contained in the Greek word μένω or meno:‘the intimate, personal, committed, continuous and reciprocal relationship between Christ and believers, whereby Christ, (and the Father and Spirit) and believers indwell one another…this relationship is dynamic, not static, an organic unity’.

In this process one component of the relationship bears witness to another. No physical proximity is necessary, the separate constituents are intimately united while retaining their distinctiveness. Another Greek word, paraclete, is also relevant here, meaning originally, ‘one called alongside.’

The photographic images, words and artwork in this collection abide with one another in a dynamic relationship that is both intimate and resonant. They move between the vividly realistic to the surreal and archetypal; from allegory to lived experience. These paradigmatic shifts invite the reader to recognise themselves within these pages, in the tension of apparent contradictions we all share. The extreme restrictions of both homelessness and imprisonment as portrayed in this book contain the potential of a journey towards liberation, and the resolution of a fundamentally human conflict.

by Livi Michael

*Proceeds from the sale of this book go to Rough Waking, the Project which raises funds for work in prisons and with the homeless.

References: Latz, Andrew B., ‘A short Note Toward a Theology of Abiding in St John’s Gospel’, Journal of Theological Interpretation, pp. 111-18. 4.1 (2010)