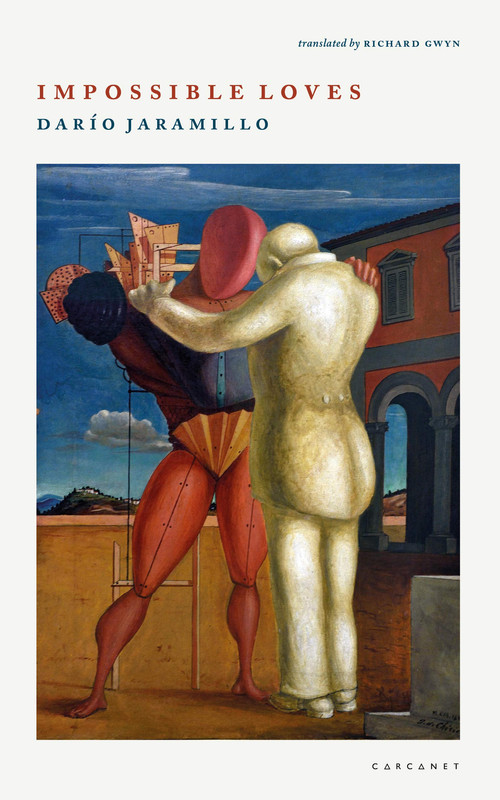

Dario Jaramillo | Impossible Loves | Carcanet: £12.99

Impossible Loves by Dario Jaramillo is a bilingual selection from the work of Colombia’s greatest living poet translated into English by Stephen Gwyn, who has also written a helpful afterword. It’s the first time that Jaramillo’s poems have been made available to an English-speaking audience, an opportunity that is long overdue, since one can have little doubt that one is in the presence of a master, a writer in the front line of Latin-American poetry and one who is revered in his own country as a love poet. ‘Reasons for his Absence’, the opening poem, is one of several where the poet invents a persona who may be his alter ego. Here, the protagonist, like Browning’s Waring or, in the real world, Weldon Kees, has gone on a fugue, vanished, ‘given us all the slip’:

If anyone asks after him,

tell them that perhaps he’ll never come back, or else

on returning no one will recognise his face;

tell them also that he left no one any reasons,

that he had a secret message, something important to tell them

but he’s forgotten what it was.

A study in apathy and ennui, the poem is reminiscent also of Neruda’s much anthologised poem, ‘Walking’, although Jaramillo’s imagery is less overblown than Neruda’s. Interestingly, both poems were written when each man was in his early thirties, yet Jaramillo sounds older, more philosophical. ‘Penultimate Imaginary Biography’ is another tour de force in which the cadences of Jaramillo’s long loping lines are eloquently rendered by Gwyn:

He lived the two or three moments that constitute life, his life, so intensely

that his memory had died and with it the chance to remember them:

but a stigma bound him to the certainty that in some way

those moments were still his;

if he were to hear me, he would not allow me to speak to you of these things …

In a later poem ‘Testimony Concerning My Brother’, he adopts a tougher, more self-assured persona; ‘But my brother has always been strong and wise, / with the wisdom of one who knows the limits of his self-destruction.’ In an exquisite sequence of twenty-one brief poems called ‘Cats’, he admires and perhaps aspires to the characteristics of that enigmatic species and joins a band of poets, one thinks immediately of Smart, Baudelaire, MacBeth, who have been obsessed by it. Here are the opening lines of the first poem:

The moon gilds the rooftops.

Unannounced, the shadows of cats appear.

They are so stealthy

they are only their shadows.

For the poet, cats are ‘not of this world …they are idlers, bored by the world, witnesses.’ Perhaps, also, it is their lack of self-awareness that is admired because a cat is ‘so idle / that it can’t be bothered with being a cat.’ Above all they don’t need words: ‘Why words / when silence is possible?’

This is of course a paradox because Jaramillo is a poet and a novelist who is obsessed with words. In ‘The Trade’, poetry is seen as ‘that battle of tired words; names for things that the noise whisks away.’ In ‘Another Ars Poetica I: Time’, he seems the antithesis of all those classical or Renaissance poets confident that they would leave behind them ‘a monument more lasting then bronze’. By way of contrast, Jaramillo writes of ‘time that continues / far beyond the vain words of the poem.’ In fact, Time, as Stephen Gwyn points out in his afterword, is one of this poet’s major obsessions. It is his heightened awareness of time and his yearning for an imagined world beyond it that explains his affinity with the Pre-Socratics and the paradoxes of Zeno. In ‘Photograph Album’, his grief for a dead friend hints at a Platonic transcendence: ‘He is something beautiful that now does not exist.’

Jaramillo’s poems are informed also by his Catholic inheritance, particularly that loss of innocence we associate with the Fall of Man. In ‘Penultimate Imaginary Biography’, we see that the protagonist cannot escape his sense of guilt: ‘the blame that surrounded him like a viscous sea.’

In the sequence, ‘Nostalgia’, the poet evokes the prelapsarian world of childhood, a world where it is often difficult to draw a line between what is real and what is imagined. Here the poet reminds one of Wordsworth in his great ode, ‘Intimations of Immortality: ‘Turn wheresoe’er I may / By night or day, /The things which I have seen I now can see no more’. Here is Jaramillo in ‘Nostalgia I’:

I remember only that I’ve forgotten the accent of the voices

I most loved,

and that I’ve lost forever the smell of the fruits of my childhood,

the precise taste of a peach,

the flurry of cold air between the pines,

the excitement of discovering a walnut fallen from its tree.

In ‘Dead Friends’ he imagines ghosts returning from their timeless zone and how they might react to seeing him so changed: his grey hair, his paunch, his apathy. In ‘Job Again’, it seems that one can only aspire to some kind of hard-won stoicism: ‘Habit or virtue, monotonous patience that I learn painfully, / slowly day by day.’

In this selection of Jaramillo’s work his love poetry is represented by two sequences: ‘Love Poems’ and ‘Impossible Loves’. The number of these which can be listened to on YouTube is testimony to their popularity in his native land and, again, a comparison might be drawn with Neruda, whose early collection Veinte Poemas de Amor is still hugely popular. Again though, Jaramillo’s tone is quieter and less ornate. Here are the opening and closing lines of the first one: ’That other who also lives in me, / the owner perhaps, or a squatter or exile in this body … / that other, also loves you’. In #4 he playfully dismantles the traditional scaffolding of love poems: ‘One day I will write you a poem that does not mention the air or the night / a poem that omits the names of flowers, that contains no jasmines or magnolias …’

What is so affecting about these poems is their truth and simplicity allied to the hypnotic effect of their cadences. The lover’s smell is her ‘unique halo;’ her voice ‘lists the things we must do together’; her tongue ‘invents’ his skin. The sequence, ‘Impossible Loves’, was written, as Gwyn informs us in his afterword, as a kind of ‘antidote to ‘Love Poems’. Here, as elsewhere, he points up a contrast between the world we know, where nothing is permanent, and some elusive Platonic realm which can only be imagined. ‘Impossible love is the happiest of loves’, claims the poet, realising, however, that it is a ‘miracle’ or perhaps even an illusion. Having suggested on various occasions Plato’s Theory of Forms, he specifically evokes him in ‘Plato, Drunk.’ The poem opens confidently enough: ‘I have experienced absolute clarity,’ an assertion which is undermined by the fact that the sage is drunk, borracho. Even the deity in ‘Conversations with God’ is unable to explain what time is and, by extension, has nothing to tell him about the meaning of life.

Just occasionally, one discovers a new poet who is indisputably in the first rank, a poet who seems, almost effortlessly, to be able to move and challenge the reader. Dario Jaramillo is such a poet and one who has been lucky to find a translator as self-effacing and skilful as Stephen Gwyn, whose versions are rhythmically adroit, musical, and true to the text and the spirit of their originals.

by David Cooke