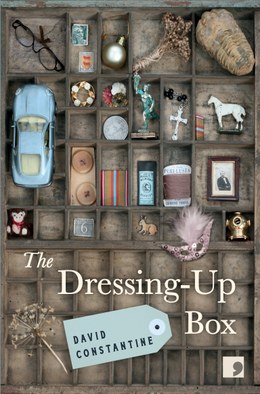

David Constantine | The Dressing-Up Box | Comma Press: £14.99

In ‘Siding with the Weeds’, the third short story of David Constantine’s new collection The Dressing-Up Room, the protagonist, Joe, goes to visit his old friend Bert. Details of place are meticulously realised; Bert lives on a cul-de-sac on an estate of ‘Sunshine Houses, all with key-hole porches, around a green’. At the back however, the gardens have gone to ruin. Bert has taken to living in his shed which contains books, maps, minerals, fossils, a microscope, a photograph of a president’s son who has shot an elephant and severed its tail, and a sign saying GLORY BE TO GOD FOR THINGS THAT ROT. The assortment of articles appears random, but Joe can see there is ‘an idea in it. Yes, bringing things together like that was the work of his old friend.’

The idea is that the world would be better off without humanity. ‘Don’t you find it a beautiful, clean thought, a world empty of people, just uninterrupted grass, and a hare sitting up?’ Bert has no doubt that the elephant in the photograph has more value than his killer. ‘If I could have saved the life of only one of them I would have saved the elephant…’

In a recent reading, David Constantine referred to D H Lawrence as inspiration. Constantine, like Lawrence, is a poet, novelist and short-story writer. He could have been referring, therefore, to Lawrence’s prose, but reading this collection, I was reminded of two poems in particular:

‘The Mountain Lion’

And I think in this empty world there was room for me and a mountain lion.

And I think in the world beyond, how easily we might spare a million or two humans

And never miss them.

Yet what a gap in the world, the missing white frost-face of that slim yellow mountain lion!

And ‘Snake’

The voice of my education said to me

He must be killed…

This sensibility is evident in ‘Siding with the Weeds’, and recurs, along with other themes such as mortality, regret, the deleterious effects of culture on nature, throughout this collection. In ‘bREcCiA’, for instance, a visiting lecturer speaks to a U3A group about a commonplace book he has discovered. The book consists of 366 pages of assembled photographs and print from newspapers or magazines. These cuttings are mainly from the 20th century, although the last entry is about the London bombing of 2005. The lecturer, who, we discover, has been recently widowed, has become fascinated by the ordering of the contents, which appears to be random, or at least, achronological, ‘aiming at simultaneity … a century or so of homo sapiens on earth’.

The lecturer searches for meaning in the book, since it is apparent to him that it has been put together with some skill. And why do we go to books if not for a sense of meaning? But his search for meaning is subverted by his deteriorating mind. Poignantly, he addresses his dead wife, ‘I tell you love, I don’t like it here in our empty house, my head is full to bursting, full as a poppy head but with every sort of seed…’

In part, he is searching for himself in the book, in the words and images which, like the seedpod of the poppy, proliferate and decay: ‘the dead letter sprouting, the spirit of anarchy giving it life. And the doodles, the marginalia, a devil showing his bum to a nun playing on a dulcimer, and the yearning, the yearning…’

Such a book might be compared to a late medieval painting by Bosch, or Brueghel the Elder. In Brueghel the Elder’s work, everyday life carries on insistently, urgently, even while miracles are happening and in the face of atrocity. In one detail of ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’ by Bosch, the shutters bear the translucent sphere of a half made universe. These shutters part to reveal a world at once fecund and decaying or corrupt. Everyday life is bound inextricably to the monstrous and uncanny, and the result, as in ‘bREcCiA’, is the depiction of a surreal world ranging from the banal to the beautiful, the horrifying and grotesque.

In ‘bREcCiA’, however, there is no sense of the overarching scheme of religion; the lecturer searches for meaning in the book and in himself, in vain. The search will only end with death ‘I am a text proceeding, I am a sentence hurrying, or dawdling, through many subordinate clauses, to the period…’

Constantine once commented in an interview that ‘at the heart of life is horror,’ and here, and in this story as in others, such as ‘Seeking Refuge’, the human capacity for art, and individual artistry is juxtaposed with humanity’s capacity for horror. The images are made resonant by juxtaposition, a technique deployed to great effect throughout the collection. It compensates, to some extent, for the inadequacy of language to fully bridge the gaps between cultures or between one human being and another, as in ‘The Phone Call’. This is a finely-wrought story in which Constantine revisits the terrain that made him famous; the places where the fabric of a long marriage has worn thin.

One of the key juxtapositions of this collection, repeated, in e.g. ‘Neighbourhood Watch’, ‘Autumn Tresses’ or the more disturbing ‘When I Was A Child’, is the contrast between childhood goodness, vitality, innocence and adult depravity, corruption or banality. It is one of the rare notes that I found false or grating. It perhaps stems from a preoccupation with theme or image, and the use of the image to generate contrast.

The other slightly grating note is that in stories such as ‘Rivers of Blood’ or ‘Siding with the Weeds’, I had the sense, perhaps because of the insistency of certain themes, that certain characters are being used as mouthpieces, or that the character’s voice is somehow conflated with the author’s own, rather than being rooted in an observed portrayal.

Otherwise observation is a real strength of this collection. It is regularly applied to the interior lives of characters. In ‘bREcCiA’, for instance, the lecturer’s talk has gone down well, yet he feels a profound relief at being alone again, followed by a ‘familiar vague regret and deepening sadness.’ And in ‘What We Are Now’, Sylvia accompanies her husband to a lecture at her old university and feels a ’fear and confusion through which pulsed a quick curiosity, the desire to learn and seize what her life needed,’ a complex of feelings in an ‘unstable mix’, beautifully rendered. In terms of the physical world, the description of the cold buffet of several decades ago in Midwinter Reading can hardly be bettered; Constantine excels at the use of the tangible detail.

The juxtapositions in Midwinter Reading are those of character and place. The unnamed narrator, for instance, begins her story by saying ‘Towards the end of my life I came to give a reading at a house on a Barratt estate somewhere in Birmingham.’ The host of the reading is Robert, who resembles a Hell’s Angel, but has a picture of Christ at Gethsemane on his wall, and another of the young queen Elizabeth II. Robert attends to the small event as if it were a sacrament. ‘I stared at his big hands, she said. That in them should be such delicacy, patience and attention brought tears to my eyes. Hours of work…’

The narrator of Midwinter Reading says of herself that she is ‘not famous…I never had much of a following. Quite often I’ve journeyed many miles and read to two or three people. Once nobody at all turned up…’

Yet in these unnoticed efforts, and unsung people, Constantine finds the sacred. At the end of her narration the writer sees Robert again, as through a mist, ‘but could make out only that he was bending over the tables, away from her. He’s taking the cling-film off the little sandwiches, she said to herself. He’s seeing to the coffee and the tea. How sad that I can’t eat or drink. How sad that I cannot partake.’ And with this apposite use of the intransitive verb, with its connotations of sacrament and participation, Constantine picks the perfect final note to a short but complex narrative of devotion and loss.

Constantine’s characters are frequently displaced, his contexts defamiliarize, his use of the image emphasises the lack of cohesion, or coherence, in man-made culture. The worlds he creates are heterotopic, yet within each one he generates skilfully, often with minimal brushstrokes, the sense of a whole life, as in the short stories of Raymond Carver. In ‘Siding with the Weeds’, for instance, Bert speaks briefly of his neighbour Freddie: ‘he’s been a recluse for years. He’d come out at night sometimes, and if it was a night when I couldn’t sleep I might see him in his ruined garden. He wore his trilby and his greatcoat, for all the world as if he were going travelling, which he never was…I never saw a man so good at standing still…

So Freddie, peripheral, rebarbative, absorbed in his own, unknowable preoccupations, springs to life on the page, created with an abrasive tenderness that finds grace in the ordinary, the marginal and forgotten.

by Livi Michael