Family Traditions

It was February 29 again, and I was wondering which member of my family would try to kill me this time. An hour ago, cousin Luke attempted to murder me with a rope. My guard was down, damn it, giving him just enough time to creep up behind me and wrap the thick cord around my neck. He began to strangle me, choking me with intertwined strands of industrial-strength hemp. I felt the rough threads press against my skin, embedding themselves within my soft, pink flesh, forbidding air from entering my lungs. I began to feel lightheaded while my face burned crimson, blueish hues appearing around watery eyes.

Before passing out, I remembered the $500 self-defence course I’d taken in October. This is it, my brain told me, as several of its cells began to die from lack of oxygen. You’ve got to get out of this mess, if you want us to live! With great effort, I stomped down on the inseam of Luke’s foot and elbowed him in the ribs. Despite the fat covering his midsection, my pointy bones hit their target. He wheezed, and his grip slackened. I swallowed down as much air as possible, and I ran. Usain Bolt would have failed to catch me, that is how fast I ran. I’m 84% certain that I left trails of smoke behind me. Fortunately, they dissipated quickly, or else Luke would have been able to follow me. Thank God cousin Luke wasn’t in the best of shape; if it had been cousin Rob, I would have been in trouble. But an obese man with a rope is no match for an in-shape woman with an iron will to live.

But why, you ask, would my own cousin want to kill me? The story begins long ago on a broken-down North Carolina farm run by a broken-down husk of a man.

On February 29, 1752, either an angel or a demon (depending on one’s point of view) appeared to my eight times great grandfather, Carrolton Summers. Carrolton had just lost his wife and three of his five children to some 18th century illness. It really doesn’t matter which one, does it? Fine, let’s just call it consumption – it seems a good catch-all disease. All three Bronte sisters died from it, so what the hell – I’ll just go with consumption. If it is good enough for Acton, Currer, and Ellis Bell (their nicknames), it is good enough for my ancestors. In the end, though, it doesn’t matter. Dead is dead.

His fourth child, a son, was sick with consumption, and he knew it was just a matter of time before his fifth one, a daughter, died as well. Though he loved both of his children, his son was far more important to him than his female child. If she lived, she’d grow up and marry a man who would take her away. His son, though, well he needed his male child because he wanted an heir. It may seem silly that a poor, uneducated, illiterate farmer in 18th century North Carolina would care about such things as legacies, but Carrolton did. Watching his son slowly waste away must have been quite difficult for him. After all, who would inherit the farm? He didn’t spend hours toiling away to see all his work be for naught. I’m assuming here. I don’t have definitive proof he wanted an heir. Maybe he just didn’t want to lose another child. Who knows? I’m cynical.

According to family lore, he sat down by a molehill and wept, the smells of the blighted potatoes, unripe tobacco plants, and wild geraniums swirling together. I’ve often wondered if the mole peeked out of its whole to see what all the noise was about, but it probably didn’t. If it had, it would have seen a thin man in worn breeches with a thin, scraggly beard weeping incessantly over his lot in life. Moles have it so easy compared to humans, don’t they?

Carrolton cursed the wasting disease that ran rampant through his immediate family, and he damned the ones that claimed his other relatives too. The sky overhead turned a dark scarlet, and all the leaves fell off the nearby trees at the same exact time. Whoosh! Thunder barked down from the heavens and steam rose up from the earth, as two hands covered with dark, course hair, slapped down atop his shoulders.

“Don’t turn around,” a voice told him. “If you look at my face, you will die. And you don’t want to die, do you Carrolton?”

“No, I suppose not,” he replied. “But who are you, and what do you want?” my eight-times great grandfather asked.

“I’ve been talking to your wife, Elizabeth, and your three children: Thomas, Matthew, and Dorcas. We’re getting ready to welcome Henry into our fold, but I know you do not want him to go, do you? You don’t want a third son to die. You’ll only be left with a daughter, Caroline, and I may or may not come for her as well. I haven’t quite made up my mind about that one. I feel sorry for you, though. I don’t know why. I rarely feel sorry for humans, but you’re different. You seem like a genuinely nice man. I’ve never witnessed you commit a sin, and no foul words have ever tumbled out of your mouth. Interesting. It almost seems as if some omniscient power hates you, doesn’t it?”

Carrolton wasn’t one for confrontation, so he ignored the thing’s jibe.

“Forgive me, but I have sinned. I try my best not to do so, but I have. I get jealous of other people,” Carrolton replied.

Whatever it was that stood behind him with its hands on his shoulders laughed. Legend has it that the laughed made the ground rumble, forcing the molehill next to Carrolton to crumble into nothingness. I’ve always felt sorry for the poor mole. I hope it had an escape route and ended up living a happy life, or as happy a life as a mole can live.

“Is jealousy a sin? I mean, is it really? I think it is part of your species’ nature to be jealous of others. I have a proposition for you – if you want to make a deal with me,” the thing with the hairy hands said.

“I will not give you my soul,” Carrolton said. “On this, I stand firm. You may wipe out my entire family, myself included, but I will not give you my soul.”

More rumbling. Carrolton could feel the vibrations from the thing’s laughter travel through its fingertips and onto his shoulders. Goosebumps sprouted upon Carrolton’s skin as the mirth-filled giggling surfed frayed nerves. Somewhere in the distance, a tree fell over.

“I don’t want your soul. I don’t collect souls, foolish man. My deal is simple: I will cure your son, and I will make sure no one in your family dies of any disease. This deal will include your descendants. You, your children, and your descendants will all die of old age or in accidents. None of you will ever know the pain of a slow death. You have my word,” it said. The hairy hands squeezed his shoulders. “You’re stiff. You need a good back rub. I know someone who can help. I can put you in touch with her later, if you’d like.”

Carrolton sat quietly, thinking upon the thing’s offer, when he heard the coughing of his last surviving son climb out of the window and into his ears.

“Tick tock,” the thing behind him said.

“What do I have to do? What do you want from me?” Carrolton asked, as he considered the thing’s offer.

“What I want from you is easy. Every four years, you are to sacrifice to me one family member. That’s it. I want a blood sacrifice every four years, without fail. Do you understand? If you do this for me, your family and descendants will never know a day of illness. No one will ever suffer from consumption. No one will ever suffer from the rotting disease. All you need to do is kill one family member every four years. You don’t even have to sacrifice the ones you love. We all have family members we hate, right? I’m being very fair, Carrolton. If I were a bastard, I’d force you to sacrifice the ones you love. However, I’m nice so I’ll take what I can get. I just want blood every four years. Do you understand?”

Carrolton thought about it, as his dying son’s coughs echoed. I don’t really like my brother’s wife. She’s a shrew. I wonder….

“Does it have to be a blood relative, or can it be someone who has married into the family?”

“It has to be a blood relative. I know, I know. I don’t like your sister-in-law either; she is a bitch. I don’t know how your brother stands her. We watch her on the other side, and we just shake our heads. Your brother and his wife, however, do have a lot of children. How many now? 10? I’m sure you dislike one of them, right? Just because you’re their uncle doesn’t mean you have to love them. The middle son, Ephraim, is a miniature version of his mother, if you ask me. He’s what – 10? You could give him to me. It is win/win, Carrolton. Your son lives, and you give a bit of misery to Dolores. Ephraim is her favourite, you know? His death would really be a kick in her ass…a bee in her bonnet, if you will.”

Carrolton nodded. “I suppose so. And for how long will the Summers family provide you with blood sacrifices? Is it just me who is to do this for you, until I die? I need a bit of clarification.”

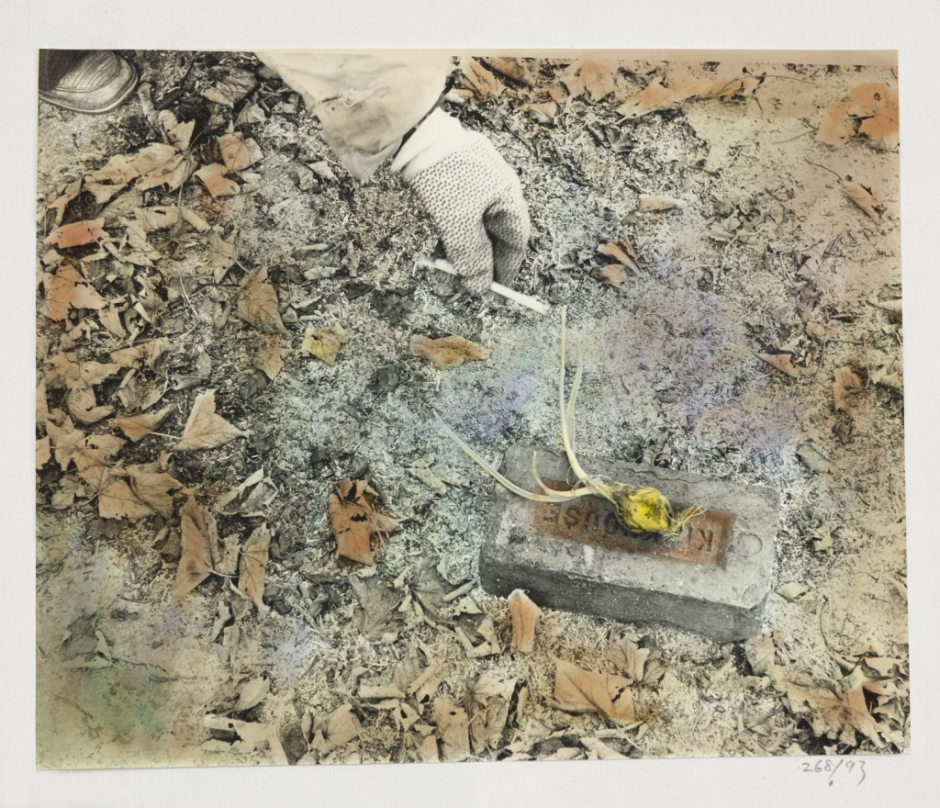

The thing rumbled again, forcing a flock of geese to take flight. Puffs of grey ash left its mouth and landed on Carrolton’s hat. We’ve kept that hat locked in a box. It is only taken out once every for years – when the eldest member of the family announces that a sacrifice is due. My dad wore it four years ago. This year, my uncle placed it atop his head. Some family members swear that they can still see the ash, but I think they’re crazy.

“Dear Carrolton,” the thing said. “This will be a permanent endeavour on your family’s part. I expect a blood sacrifice every four years, until the earth stops spinning. You will have to explain to your children and their children the importance of the sacrifice because, if I don’t receive one, your family and your descendants will experience every disease known to mankind. The ones now are bad enough, but can you imagine the ones still left to be discovered. I mean in 1928, there could be all kinds of horrible diseases just waiting to infect your family.”

Carrolton’s brows arched, wrinkles cutting through his tanned forehead. He closed his eyes, and he stroked his schnauzer-like beard.

“What if the chosen sacrifice doesn’t want to die, even if he or she knows what could happen to the family if there isn’t one? What then? And when you say blood sacrifice, do you mean that blood literally must be shed? Could the intended sacrifice be hanged or poisoned?” he asked, his eyes still closed.

“You’ll find that will be the case, Carrolton. No one wants to die. The chosen sacrifice will fight to the bitter end. It isn’t easy for a person to give up his or her instinct for survival. Even the dying try to hold on to every minute scrap of life the gods deign to give them. They wheeze air into their putrefying lungs and hold it for as long as they can, as if it will help extend their lives. It is pathetic, really. People want to live for as long as they can without considering the quality of their lives. As far as whether you can use poison, the answer is no. It taints the blood. I would prefer actual blood be spilled, but I won’t scoff at garroting. I’m okay with it. Oh, and no burning. I don’t want my sacrifices crispy.”

The thing squeezed Carrolton’s shoulders once again. “I’m not making this offer lightly. I feel sorry for you. I don’t know why. I know I shouldn’t, you are human after all. But I do feel sympathy for you. It must be hard for your breed to stand back, helpless, and watch your children die. I’ve never had them, but I’m smart enough to know that you humans harbour a certain amount of love for your offspring. Thus, I’m making my offer to you. Good health for you and all your descendants, for blood every four years. I think it is fair, don’t you?”

The thing removed one of its paws from Carrolton’s shoulder to scratch someplace on its body. The man wasn’t sure where, but wherever it scratched, a noise that sounded like dried husks of corn being scrunched echoed in the air. The crackling entered his ears as he pondered the thing’s offer.

I like to imagine Carrolton sitting in the middle of his field, crops sprouting out here and there as he considered the deal. What was he wearing that day? I’m sure he wore breeches, but what kind? What colour? Were they black to match his hat? Did he even care about fashion? It is a mystery to me, and it will remain one until I take my last breath. Perhaps, if I’m caught, I’ll have the opportunity to ask him in the afterlife. Mostly, I wonder what he thought as he pondered the deal. Did he think about his descendants? Did he care that one of us would have to die? Did he glance back at his house, where his son lay in bed slowly dying of consumption? Did he realize how useless his farm would be with only a daughter as his heir? I’m sure he did. And he obviously agreed to the deal, because here I am trying to hide from my family.

“Aye,” Carrolton said. “I agree.” The thing patted him on his back. “You’ve made the right choice,” it replied.

According to his journals, the pact was sealed with fire and salt. I have no idea why they couldn’t have just shaken hands (or paws) but no – the thing had to be dramatic. Eight times Great-Grandfather Carrolton had the flesh between his shoulder blades branded with a circular shape that had an octagon in the middle of it. Before it could cool down, the thing shoved salt into it. I’m sure Carrolton screamed. I would have. Then the thing kissed it, and all the pain went away.

“You have until sundown to give my sacrifice,” it told him.

Having been told that only a blood relative would do – lucky for Dolores, I suppose – Carrolton rode his horse two miles to his brother’s farm. The sun started to dip towards the horizon. Each elongated shadow taunted him. Tick tock, they said. He knew he had only five hours until sundown. He’d have to be quick.

“I could snap my nephew’s neck. He said garroting was acceptable, I should think a snapped neck would suffice. I have my knife with me. Maybe I could slit his throat whilst no one is watching. They live near a creek. If I could get him down there, without them seeing, I could cut him from ear to ear or stem to stern and blame it on the Natives. No one would think an uncle would kill his beloved nephew. Yes, I just have to make sure I’m with them when the body is found.”

He smiled to himself and slapped the flank of the horse, telling it to gallop faster. “There’s blood that needs to be spilled, Sergio.”

Carrolton raced time in desperation, a man on a horse battling a foe over which he had no control. His son’s coughs rang in his head, as death laughed at him. Do you really have the intestinal fortitude to commit nepoticide? He’s still a child, after all. He knew a taunt when he heard one, and he thought of the times he had to bury his wife, two sons, and his baby daughter. Never again, he told himself. No one in my family will ever suffer like I have ever again. They better be grateful – for what I am about to do may surely send me to hell.

To Carrolton’s immense luck and relief, he saw Ephraim nearly a quarter of a mile away from his home. He was near the creek, shirtless, slapping his wet shirt onto hard rocks. “The foolish lad must have fallen into the water. I’m so grateful he didn’t drown. I don’t think it would count,” Carrolton said. The thwap thwap thwap of wet cloth against the granite reverberated in the air and masked his arrival.

This is an actual passage from Henry’s, Carrolton’s son, journal describing the moment when his father murdered his own nephew, thus saving his life.

My father rode his horse as fast as the beast could run. He was desperate to save my life, for which I am grateful. I shall always be indebted to him for his decision. He could have allowed me to die, instead of making the pact with whatever it was that appeared to him on that day, but he did not. Here is what my father told me about what happened that day on February 29, 1752, when he murdered his own nephew.

“I spied Ephraim near the creek, cleaning his tunic. He did not see or hear me ride up behind him. He had been warned in the past to pay heed to where he was and who was around but, to my great fortune, this time he did not. I dismounted from my horse, and I looked around. We were all alone. The only witnesses to what was about to happen were the birds in the trees and whatever God lived up in the heavens.

I sneaked up behind him, knife in hand, and I put my hand over his mouth, so he could not scream. He kicked me hard in my legs and stomped on my feet, but I did not let go. I told him how sorry I was. He must have known it was me behind him because he went limp. I slit his throat and tossed the body into the creek. Making sure that there was no blood upon me, I washed off the knife. Then I got back on my horse and rode to my brother’s cabin.

He welcomed me into his abode, and we drank ale and ate bread. Dolores started to get concerned that Ephraim had not returned home and asked me if I’d seen her on my way over. I told her I did not. I was calm when I said it. I felt at peace. It was easy to lie to them. I do not know why.

Dolores ordered my brother and me to ride along the creek bed and look for the boy. We did as she bid, and we rode off. I led my brother into the opposite direction, not wanting my nephew’s body to be found so soon. We rode for a mile, and the sun dipped lower – nearly kissing the horizon.

After awhile, my brother said we should go in the other direction and, not wanting to raise his suspicions, I agreed. As we rode, the stars began to dot the sky, and the crickets and frogs began to sing.

An hour or so had passed, and I heard a scream flee from my brother’s mouth. He had spotted his son. He jumped off his horse and ran over to where Ephraim’s body lay. He grabbed him into his arms and began to cry. I felt no sadness, only fear. What if my boy was still sick once I got back home? What would I do then? I knew I would not be sorry for killing Ephraim. I had lost three children to the consumption. My brother had lost none. Why should I be the only one to suffer the loss of a child?I helped my brother place his son’s corpse upon his horse, and we shared mine. I could hear him weep behind me, and I felt nothing. I wanted to ride home as fast as I could to check upon my son, but I could not. I had to help my brother take his child’s body home.

We arrived at the cabin, and Dolores was at the door. She saw her Ephraim’s body on the horse, and she screamed. I felt no pity for I had never liked Dolores. I helped my brother dismount Ephraim’s body from the horse, and I promised him I’d be back tomorrow to help find the bastard that had done this to his child. I said to him that I wanted to go check upon my own children to make sure they were okay and had not met the same fate as my nephew.

My brother understood. He thought it was the Natives that did murder his son. I did not correct him. I agreed that it must have been the Natives so as to not arouse suspicion towards myself.

Upon arrival to my own cabin, my boy was sitting up in his bed. His cheeks were no longer a chalk-white and blood no longer stained his lips. His skin was a healthy pink, and he greeted me with a smile. I fell to my knees and cried. Then I thought about who would be sacrificed four years from now. Perhaps it would be another one of my brother’s children. I promised myself to explain the pact to my children after the second sacrifice, when they both were older.”

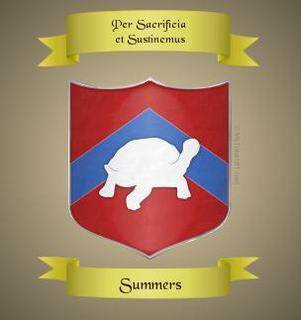

Obviously, Carrolton explained things quite well to his children because here I am trying to hide from my family. He even created a Coat of Arms for the family:

Apparently, the crimson is for sacrifice and the blue is for loyalty. The shield represents protection and the turtle represents invulnerability. Fitting, isn’t it?

From 1752 until 1864, the patriarch of the family decided who would be the official sacrifice. It changed that year, due, in part, to guilt. Yes, guilt. After 100 years, someone finally felt guilt. Better late than never, I suppose.

In 1864, during the Civil War, my great-great-great grandfather, George, shot his brother as that year’s blood sacrifice. The crime was easy enough to cover up because, in war, people die. That’s how it has always been and always will be, as long as war exists. I guess the one thing I can be proud of is that both George and his brother fought on the Union side – my family aren’t racists, after all…well, Carrolton and his brother were but people evolve over time.

George felt so bad about killing his brother that he instituted what we now call The Family Draw. Ten people are chosen by lot to sit around a table. Once all ten are seated, a bag containing nine black marbles and one white marble is passed from person to person. No one can open their hand to peek at the colour of the marble; that would be cheating. Whoever draws the white marble is the designated sacrifice. Great-great-great grandfather George felt it was fair and far more democratic. Women were finally put into the pool in 1920, too late for the leap year sacrifice held that year but just in time for the 1924 leap year. “If you can vote, you can die,” was my great-grandfather’s logic. I consider myself a feminist, but sometimes I wish there wasn’t equality. I wouldn’t be trying to hide from my family, if there wasn’t. C’est la vie.

The first woman to be the designated sacrifice was my grandfather’s sister, Evelyn, in 1952.

Evelyn Summers Layne had five children under the age of eight. I’m told that when she revealed that she had drawn the white marble, she smiled a little. Who wouldn’t? One child under the age of eight is daunting enough – but five? I can’t say I blame her.

Her family took her to the woods, whilst her mother watched over the children. Kids always love their grandmas. Grandmas bake cookies and play. They dry tears and bandage scraped knees. Or they used to do so. Mine is trying to kill me. I can see her peeking inside the window with a knife. I think it is the same knife my grandfather uses to carve up the Christmas ham.

Back to Evelyn. Her brothers, father, and two cousins drove her twenty miles outside of town. They pulled onto a snow-covered spit of land that sat between two frozen creeks. Evelyn didn’t bother wearing a coat. “Why bother? You’ll just get blood on it. You may has well give it to someone else,” she said.

She ran, half-heartedly, in heels, pretending to avoid her predators. Behind the trees, she and her brothers were hidden from the main road. Great-Uncle Michael said she stood by a thick oak, looked at him and nodded. He kissed her on the cheek, and then drove an ice pick through her heart. She thanked him, and then she fell to the ground and died. Her father and brothers got into the car, and they drove away. Later that day, her mother filed a police report. Evelyn’s body wasn’t found until May. Her “killer” was never found. It remains an unsolved case to this day and is one of the most famous murders in Altoona County. Everyone talks about the phantom killer of Altoona County.

I guess I can admire Aunt Evelyn. She gave her life so her family, including me, could endure. She didn’t mind leaving her five children motherless. I wonder why. Maybe she didn’t find motherhood so fulfilling after all. Or maybe she was grateful that she had saved the lives of her children from God knows what kind of disease. But she went without a fight. I wish I could be so charitable, but I’m not.

So, here I am – the third woman to be the designated sacrifice. On the one hand, I’m proud of the progress the women in my family has made. We’re serious contenders for the official sacrifice AND we can take part in the hunt. On the other hand, I don’t really wish to die. I have a great job, and I’m supposed to go to Paris next month. I’m flying first class, for God’s sake! Plus, I still haven’t been to the Bahamas, and everyone goes there. I really didn’t think, when I plopped my ass down into that tenth seat, that I’d be chosen. Maybe it is hubris, I don’t know. But I did not think it would be me.

I know I’m being selfish, and I know I’m risking the health of my entire family, but I think pacts should come to an end at some point. I mean, how fair is it to the rest of us? Carrolton was desperate, but we now have a very large family. We could afford to lose a few members to cancer or any other disease. The family name will still go on. My father says we can’t take that chance…that we need to uphold our end of the bargain. “A deal is a deal,” he likes to say.

Perhaps he’s right. As for me, my time is up. I’m in a room without an escape. My grandmother stands at the only window, smiling at me as she strokes the knife. Cousin Rob is at the door. I am pretty sure that he has a sledgehammer. I guess I’ll go ahead and open it. After all, he’s strong and one swing should do me in. At least it will be quick and somewhat painless. As our family motto says, “Through Sacrifice, We Endure.” I just hope they appreciate and remember me, seeing as how my skull is about to get caved in. If not, I could always haunt them.