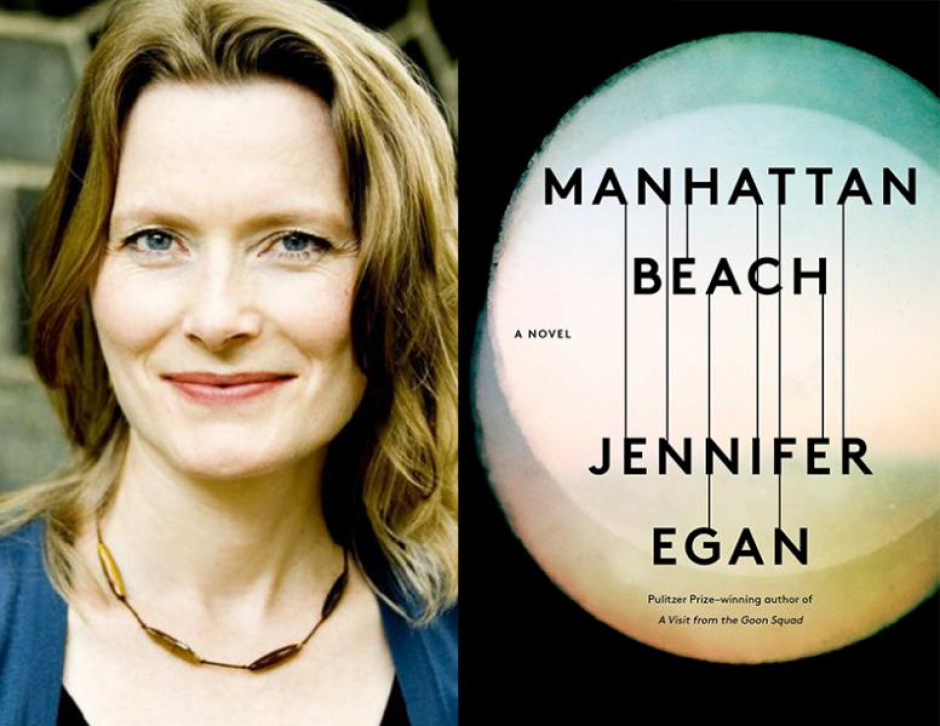

Jennifer Egan, hosted by Katie Popperwell at the Manchester Central Library.

It starts out like any other highbrow reading. Lights down low, jazz, a room full of chattering literati (some of them refusing to take off their fedoras). Then Egan and Popperwell walk out and…silence. We’re meant to be clapping right? The audience are looking at one another but it’s been quiet too long; we can’t start now. Popperwell tries to begin but her pages are stuck together. Cue a minute of alternating apologies and what sounds like sticky back plastic being torn from a microphone. There are only so many rounds of nervous laughter in an audience—we run out well before things are ready to go.

And so, we putter into an introduction. Egan stands and, sensing the stiffness in the room, goes for flattery. Her first visit to Manchester is impressing her; the building we’re in only comparable to the New York Public Library. We knew that already but it’s always nice to hear it from someone else. The awkward spell lifts and we’re into the reading.

It’s worth the wait. Heck, it’s worth the seven year wait we’ve had between 2010’s Pulitzer Prize-winning A Visit from the Goon Squad and this, her latest novel, Manhattan Beach.

We’re on the New York waterfront after the crash. Gangster territory. Anna Kerrigan is our pre-teen protagonist, tasked by her father with tying up the local mob boss’ children and making him look good. Egan’s linguistic ease is remarkable. From a housewife with a ‘movie star’s painted eyebrows’ to the boss’ grinning ‘as if her reply were a ball he’s taken physical pleasure in catching’. A future Brooklyn Navy Yard worker in the war, Anna plays with a trainset and is described as feeling ‘the logic of mechanical parts in her fingertips’, coming so naturally that ‘she could only think that other people didn’t really try’. I’m hooked.

But more than all that, Egan achieves the impossible: a character says the word ‘toots’ and I believe it.

During the Q&A (Popperwell’s sheets are now unstuck), we learn of the effort that went into writing the book, Egan’s first historical novel. She’s been at it for fifteen years, engaging in oral history projects in that time to capture the memories of the women and men who worked the wartime navy yard, those still alive now well into their nineties. We hear of the Byzantine way Egan goes about her writing process—writing longhand, typing up, reading what’s there, making seventy-odd page dossiers of notes, and all that’s, in her own words, ‘before even working out what the book’s about’. After that it’s a rinse and repeat cycle of hard copy revisions, notes, outlines, etc. No wonder we’ve waited so long.

The surety and eloquence of Egan’s answers make it hard to judge the level of spontaneity we’re getting. Is this the polish of the literary scene—answers ground and honed on the festival circuit? Or are we getting something fresh—are we seeing that sense of improvisation she tells us is so important in her writing? The purity of each thought has the whiff of the former but then again, as our host puts it, we’re in the presence of a ‘super-thinky writer’.