This is how it will start. You see him on stage, strumming a blue Stetson, his mouth tightened in concentration. You look at him through your viewfinder and capture him singing along with the chorus. He looks directly into your camera, and you let it hang loose around your neck. You hold his gaze, then look away. It will be a game, and you will win. That is how it will start.

Say you invited yourself along after the show—not to see him, but to talk to the taller one, the singer. Say the taller one ignores you when you ask who inspires him. Say you can only snap the singer from behind when you ask for a shot for the paper, but the guitarist looks at you head on. Say you talk to him then, instead, and he talks back but doesn’t listen. Say you touch his arm frequently, and nod when he asks if you think Santana is the greatest guitarist of our time. Say you find him boring and simple, but agree to meet him again, only to see if the taller one will notice. This is how things will complicate.

When he comes to pick you up, tell yourself it’s only one night. Tell yourself first impressions are deceiving, that maybe he’s one of those guys who can only listen when he’s sober. He will not be one of those guys. Agree to go to La Rose, the only fancy restaurant in town, even though it’s a forty-five minute wait on a weekend.

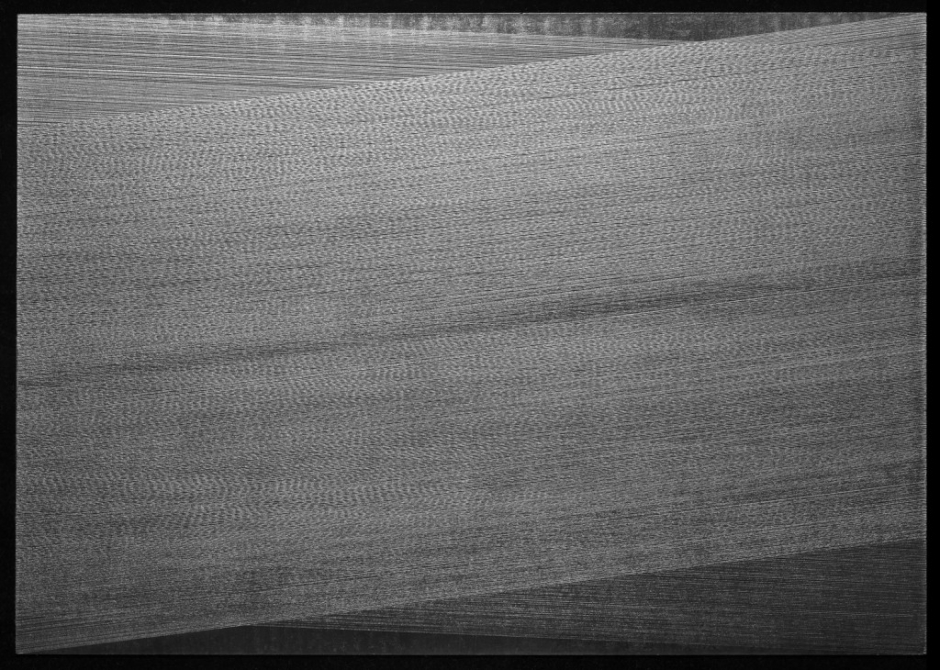

Regret it. Watch as he sits next to you, squished close on the small corner waiting booth, and note how his mouth continually moves in a slow circle, a nervous, slow-moving tic, and even though you’ve never seen a cow up close, you will know instinctively that this is what one would look like, chewing cud, gazing into the emptiness of an Iowan cornfield.

When he drops you off that night, he will not try to kiss you. You will feel grateful, then confused, then angry. This is when you will go inside the house and call an old boyfriend, it doesn’t matter which, so you can listen to him say, You’re beautiful, you’re sexy, like a repeating chord, lulling you to sleep.

Take Lucie out for lunch the next day. Say, Mimosas needed, and she will know. Tell her about the cud chewer, but leave out the part about the singer. Tell her you don’t care that he didn’t kiss you, and wait to see whether you should. Lucie will laugh and look away and tell you about her night without commenting on yours. Order another mimosa. Decide you need better friends.

When he calls to ask you out again, your mouth will form the word, Yes. You are a good, Midwestern girl. You will know not to say no.

Notice how his hair is thick and black, and that he has long eyelashes, and abs that you can feel when you lay your head on his lap, your hands tucked beneath to smooth your hair. Notice also that his hairline is receding, and his eyes stare dumbly beneath those eyelashes, and that you have no desire to take off his shirt. This should be your first sign.

You will begin to see him more often. When friends ask if you’re serious, tell them cancer is serious. Tell them he is your muse, in an uninspiring way. Tell one friend, who lives very far away, that this is your study in hatred. Tell your mom that he makes you happy. She won’t believe you, but she won’t press you for details just yet.

The sex will be easier than you thought. Detach yourself. Imagine you are sitting at the far end of the room, and take notes on his technique. He will look confused for most of it, and will jump from one thing to another, pressing different parts of you until he gets the desired sound effect. Let him learn through trial and error, but discover he likes to keep with the same patterns. Lie extremely still and see if he notices a change. He won’t. Take mental snapshots during each stage of the process. When he orgasms, his face will go from confused, to scrunched up, to rigid, to blank, in equally timed stages; his expressions will remind you of your computer struggling to change tasks when it is bogged down with multiple viruses. In the beginning you can fake it, but after a while you will realize there is no need.

You will notice, slowly, that you are becoming a thing. An item. When friends call to invite you places, it is implied that he will be included. You may find yourself using his slang—it will sound distant and foreign, yet familiar at the same time. Listen to yourself say sweet and shit-show and, worst of all, that’s what she said. Your friends will think it’s cute. Feel betrayed. This means you’ve given more of yourself than you have during the ten-minute thrustings that have dwindled down to once a week. This is when you will lose control of the situation.

You begin to spend the night, always at his place, never at yours. At first this will feel like your decision, but slowly you will notice that you have become the other, the guest, the visitor. On Sundays he makes you breakfast. The first one will be served on a paper plate. The eggs will be runny, the bacon rubbery, the toast black. Swallow it down anyway. He’ll want to eat breakfast naked. Agree, even if the sight of nipples and body hair amidst runny eggs makes you feel slightly nauseous.

One night he will whisper those three offending words into your ear. Feign sleep. Hold your breath like you used to do on Sundays when your mom would try to wake you for church. Count the seconds until he lowers himself back down to the pillow. Let your breath out slowly, in increments. Your chest will burn, and no matter how many times you inhale afterwards you will still feel as though you don’t have enough air.

He will start to say love more freely. The first time you say it will be on the phone. It will be harder, then, to ignore the passing time as he waits for your response. You won’t be able to fill the space by touching his arm, or laughing, or sucking his penis. Say the words back. After you say them, you will feel unchanged. Indifferent. You will start to say it often—ending and starting most conversations with the words. They will begin to feel empty, like a salutation, and it will feel okay to say them automatically, whenever he says them to you. Much later you will tell people this is the worst thing you’ve ever done.

Start to hurt him. Not overtly, not at first. Cook dinner for him and sprinkle the chicken with crushed peanuts. When his face swells up, tell him you forgot he was allergic. When he starts to tell a story at his friend’s birthday, sigh heavily and comment how many times you’ve heard it. Roll your eyes. Make others feel your exasperation. When you go to his shows, refuse to meet his gaze—stare instead at the tall singer, the drummer. Mention over dinner that you think you might be into girls.

Sometimes he’ll get angry. Yell at him. This will feel good. Tell him you should be the one angry. Write down his faults, and then read them to him. Tell him you deserve better. Tell him he does not. Drink while you’re fighting so you have an excuse to become meaner. Tell him things you’ve been holding back, so you can forget them in the morning. He will join the game occasionally, but mostly he will sit down and stare at his hands. He will ask what he did wrong. You’ll mention something small—he didn’t pay for your drink, he embarrassed you at the party, he still hasn’t fixed the thing that is broken. Leave the big ones for later. Hide your indignations like ammunition in your pocket. I’m better than this. You’re holding me back. This is not what I wanted.

You will wait for the end, the breaking point. Instead, a curious thing will happen—something you will not understand until your late twenties. You will get meaner, and he will get nicer. You will throw a glass, and he will catch it and return it to the cupboard. You will scream, he will nod. You will threaten, he will plead. You will leave, he will stay. When he comes over to hug you, let him hold you but don’t hug back. Let your arms hang loosely at your sides and imagine yourself caving in as he squeezes you. You will feel as though pieces of you are falling away. This is normal. You feel as though those pieces are never replaced. This is not.

Decide to search for those pieces. Tell him you need to travel abroad (it doesn’t matter where). Tell him there are things you need to do. Use your camera as a weapon. Shake it at him, and tell him you’re tired of cataloguing images of complacency and perpetuity for prosperity; when he asks what you mean, tell him he wouldn’t understand, even though you really don’t either. Offer to give him his space, but agree to be “long distance” when he says he doesn’t need it. This new label will remind you of the special calls your mother would make to far-away family members when she had extra minutes at the end of the month. Think how this is really not much different.

Go to Europe and have sex with strangers. Catalogue them away for future reference. Try infidelity on like pants that once fit but now feel baggy around your thighs and hang loosely around the crotch. Meet up with a friend who tells you nothing counts in Europe. Decide she is right, and stop counting. When you email him, list the places you go—but hide the names until the trip is over. Florence—Jonas; Prague—Christian; Barcelona—Roberto.

When he asks who you’ve met, say you are becoming immersed in European culture. Tell him to come join you, but only because you know he hates to travel. Get angry when he suggests you are cheating. He will know about the men, but will not ask until you tell him. Wait until you come home and then give him detailed accounts of every encounter but one—keep this one, the last one, for yourself. He will ask you curious things—he will want to know names, what they looked like, whether you kissed them, whether you liked it. Humor him at first, but when you can’t recite each of their names for him, become defensive. Tell him what you most remember is they all loved going down on you. He will stop asking questions, then. When he agrees to stay with you, this will be the last important decision you will remember making, although technically it will not be your own. For the first time, wonder what he sees in you, whether it even matters.

One afternoon, when the hurt has begun to fade but has not yet left, dense like fog around your words, he will ask you to write down what you love about him. Pen in hand, blank paper in front of you: this is the first time you’ve been forced to qualify your decision. Write, Because you’re a good kisser, and cross it out. Write, Your music, and, The way your hair looks in the morning, and, Because I’m afraid no one else will love me, and, Because I don’t know who I am without you. Cross all of this out. Write, Because you’re a good kisser again. When he shows you his list, it will be pages long, and typed. The list is sweet. It mentions the color of your eyes, and the way you twirl your hair around your finger, and how you love old slasher movies. Hide your own. Tell him you’re still working on it. Throw your list away and write him a card, instead. Inside, write, Because I’ll never find someone better than you. He will put the card on his bedside table, and you will always feel slightly unsettled when you see it.

When he asks you to move in with him, nod your head. Don’t answer out loud. Curse your mother for raising you in Minnesota. The move itself may interest you. The shifting of objects, clothes, kitchenware, futons. His apartment will take on the look of a refugee camp, but only for the first month. You will have to put your mattress in the garage because he already has one—a nicer one, a Temperpedic. Put a tarp on it, even though it won’t matter. Two years later when you finally agree to donate it to Salvation Army you will notice a family of rats have eaten through one of the corners and laid claim to most of the insides, and you will be forced to lean it against the green metallic dumpster. But for now, place it carefully in the garage—lay the tarp precisely, tucking in the edges. Take mental note of everything you put into storage. Unpack, but only slightly. Leave some of your clothes still in the suitcase, at the bottom of the closet. Leave your kitchen things boxed and taped up in the corner. When he suggests selling one of your futons, convince him that you need the extra seating even though it has become an obstacle course to go from one room to another. Treat the move like a visit to an unfamiliar home. Keep your jacket on until someone makes you take it off.

One day you’ll notice that your suitcase is empty, and your dishes have found their way into the cabinets. This is expected, this is normal. Start to notice that you’re the only one who does anything. Begin to record the amount of chores you do. Clean excessively to point out his inadequacies. When he comes home from work, throw the vacuum around like a gun-slinger so that he has to tuck his feet under the couch to avoid being run over. Glare at him while he watches Cartoon Network. You do not like housework, but this will not matter. You only cleaned your last apartment when your mother came to visit, but this will also not matter. As you wipe down the counter, comment on what a long day you’ve had. He will tell you to join him on the couch. Sigh audibly. Wonder if you can still be a stereotype if you recognize the signs. Wipe hair out of your face with your sponge hand. Call your friend who lives very far away and tell her it’s actually turned into a study of futility.

Another thing will start to happen. Something you will understand in pieces later on, but never fully. When your furniture and clothes and plates and forks and shampoo and towels and sheets and pillows mix, you’ll stop recognizing what is his and what is yours. You will write a different story of how you got here, and you will forget how to get out. It will become necessary to throw away your list of what he does wrong, and replace it with reasons you shouldn’t leave. Write instructions for making it through the day; leave lists of to-dos clustered on your desk. The weeks will become long, the conversations forced. You watch television together. You retire your camera to the bookshelf, and he puts his guitar in the storage space. It won’t be because of him, exactly, but you will change. Notice smaller changes at first, like the weight gain. The bigger changes will sneak up on you; you stop traveling. You watch his television programs, even though they used to annoy you. You don’t see your friends. You have nothing left to capture behind your lens. You stop trying to convince your mother you’re happy and start working to convince yourself. You stop having sex. Be grateful for his king-size bed. Hug your side, even though there is more than enough room. Let the space speak for you.

You will adjust to this life. It will become necessary to forget the things you once said about him, and replace them with new thoughts, new conversations. There’s no word for what you become; you won’t fight so much anymore, but you will not be content. Apathetic, deluded, reminiscent, conflicted. Roll the words around on your tongue, try them on. They won’t feel right, but it’s necessary to consider them. If there were words, a description, a small snapshot of the person you are in this moment, it might go something like this: When you are unsure of whether to throw something out, and you find a place for it on your shelf, and time goes by and you begin to develop emotions as to why you can’t throw the thing out, and it sits, collecting dust, and even when people ask you the reason that thing is important to you—be it a blackened pressed flower, a dented metallic bank which holds no coins, a greeting card from a person you no longer can picture—you can no longer recollect it, because there was never a reason to begin with, but you simply can’t bear to part with it now, because there would be a hole where it once was, even if it was never necessary to have that hole filled—and perhaps that is why it is better not to find words for this moment, this state of being, because even now you can’t fully understand the person you have become until you are there, until you are that person.

It will become necessary to avoid both your mothers. His will hate you. She will smell your indifference through your bright yellow shirt the first time you meet. She will ask you to leave him, which will only make you dig your heels deeper. Your mother will be more subtle. She will ask about your school plans, remind you of your desire to teach abroad. She will dangle other options in front of you just as she would use a treat to coax your childhood dog out from under the bed. Despite both your mothers’ efforts, he will give you a ring one day, it will fit, and you will accept. Afterwards, wonder if any other woman has accepted a proposal with the phrase, Sounds good.

Say you get married. Say you move west, to follow his job. Say you have children, and decide to stay home with them. Say you replace your albums from Europe with snapshots of your children eating and sleeping and playing. Say you fill your days with soccer games and art class and permission slips and cheerleading practice and Disneyworld trips and homework assignments and bag lunches and schedules and carpools and conferences and piano lessons and Jello and sticky hands and fleeting hugs and family dinners. Say you put your life on hiatus for a quarter of a century to watch your children grow.

You will hear of women that have it all, but you will not be one of them. The children will provide a necessary distraction from your marriage, but it will only be temporary. What no one will tell you is that once your children leave, it’s important to have something else. You will recognize this, but it will be too little, too late. Join book clubs and Bible studies. Take yoga classes. Ask him if he wants to try that threesome he mentioned before you were married. He’ll look at you, the blank, computer screen stare, and say you must be thinking of someone else.

Consider having an affair. Confide in your youngest daughter—the one you have the most hope for—late one evening at a local bar near her college. Give her pieces of your past, and let her connect them. Tell her you don’t love her father, and ask her if she believes in second chances. She will sip her drink, tuck her hair behind her ear and glare. Grow up, Mom, she’ll say. I’m trying, you’ll think. Shift tactics. Ask her about college. Ask her if she knows any tall singers. She’ll sigh, and lean back on her bar stool. I don’t get you sometimes, Mom. Laugh, and tell her that’s good. Take her hand, and tell her that’s a good thing.

This is where it will end. Go home. Let him see you cry. Curl on the bed like a child. Let him mold his body to yours. He will ask what is wrong, and you won’t be able to tell him. He’ll say, Are you okay? over and over, like a chord, like the music he doesn’t play anymore. He will stroke your hair, rub your shoulders, try to knead the grief from your body, and you will let him. When you finally answer, Yes, I’m okay, it won’t feel like a lie. Turn around and cling to him hungrily, greedily. Say it louder, I’m okay. You’ll feel the familiarity of his legs scissored between yours, his hand around your neck, your chests pressed together, your forehead bowed into his shoulder, and it will feel certain, it will feel good. One of you will have to pull away eventually, to shift positions, or answer the phone, and when this happens everything will go back to how it was before: but still, in this moment, what you have will feel more than enough.