Like everyone else bludgeoned by these billboard harangues and television films of imaginary accidents, I had felt a vague sense of unease that the gruesome climax of my life was being rehearsed years in advance, and would take place on some highway or road junction known only to the makers of these films.

— From “Crash,” by J.G. Ballard

The films were usually shown, where I grew up, in school libraries during the normal run of the school day, no doubt because the school authorities were certain they were not in the least entertaining, which they indeed were not, nothing like the kind of films that we gladly paid to see in the theaters of a Saturday morning or matinee, spectacular productions shot in glorious, hyper-realistic color and filling panoramically wide screens. The school films were in black and white, and shown on small, roll-down screens. To be sure, their black and white was somewhat modern-looking, a well-lit, subtly-shaded, well-defined black and white, perhaps the latest that was in use before the switch to color became universal, a black and white that seemed on the verge of turning into color. Yet it was still black and white, which meant that it was technologically out of step with our generation, aesthetically handicapping the films in their mission to reach and affect us. Each time these films were shown they managed to convince us – an audience of film-crazed children who could have forgiven film just about anything, possibly even black and white, so enamored of the medium were we, so magical did we usually find images moving luminously in the dark – that a film could after all be not only boring but almost clinically unpleasant, endowed as these films were with an atmosphere of doomed claustrophobia that might have been compared with that found in noir or even horror films, except that the school films did not have the redeeming quality of being in the least intriguing or thrilling. And it was, this dark atmosphere, always present even though the scenes were usually set not at night but in broad daylight and ostensibly in cheery everyday life.

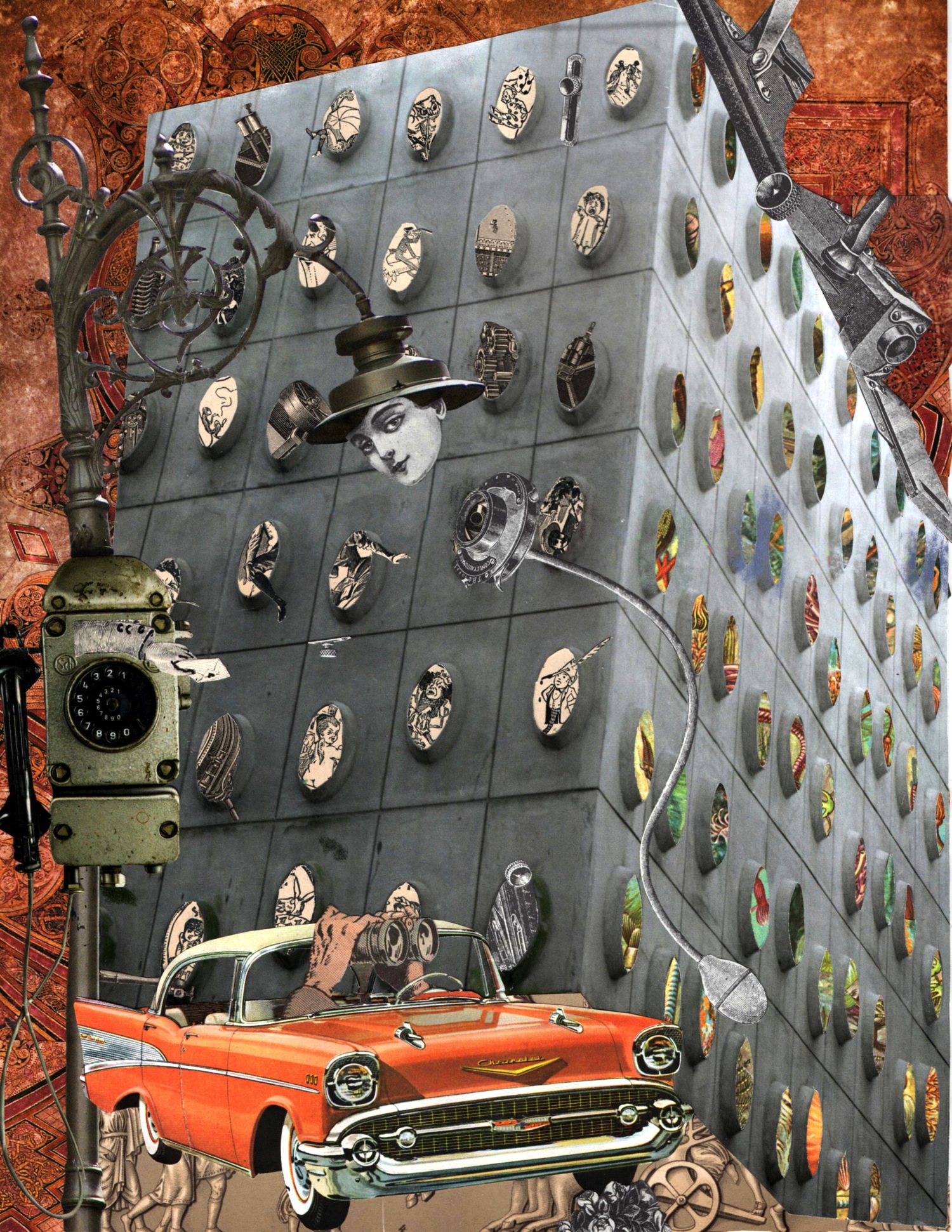

A man in a reasonably modern suit and tie finishes breakfast, says goodbye to his pretty wife, leaves for the office; a set of tow-headed children play ball in a yard or park; a cute little girl in pig tails and a checkered frock pedals a tricycle along a painfully neat sidewalk: scenes which could not easily have looked more innocent, cleaner, better lit. Indeed, so perfect, so devoid of the grit of reality, of its accidental gestures, chatter, and clutter were they as to seem ominously sterile. It was as if everything and everyone in them were already as good as dead, as if all had already ended badly and this were merely a wooden reconstruction of how innocently commonplace things had been. This was probably an unintentional effect, but it felicitously added to the dread which the filmmakers were trying to build by other means, by the deployment, for instance, of a minimal, mediocre but anxious classical music soundtrack, or cuts between disparate scenes that, though leisurely or almost unnoticeable at first, occurred at ever shorter intervals, making it obvious that banal and apparently disconnected events were ominously launched on a collision course. More subtly, every car, bicycle, ball, running child or other moving object would be filmed to appear as if somehow beyond control, hurtling on without hope of intelligent steering or braking. A car backing out of a garage would, for instance, be seen through a camera placed very close to the asphalt, which made the vehicle look as if it were blindly rolling backwards down an incline. From within the car as it traveled down the road (presumably having emerged from its driveway without incident, having skirted that particular peril,) the viewer could see how the frame of the windshield and the car’s hood moved in ways that seemed to bear a somewhat disjointed, skittish relation to the road ahead. Driveways and intersections suddenly, treacherously, perhaps with a slight but nonetheless ominous swell of music, came into view, as if about to disgorge feral animals onto their prey. Head-on shots from outside the moving car would also seem to emphasize its instability, showing how jittery its body was, how freely the steering wheel moved under the driver’s hands, fairly spinning when he turned round a bend or corner, as if the car had lost traction on ice. And the driver and passenger would be seen too clearly, as if their noses were all but touching the windshield.

The vehicles in these small-budget films may have been not really driven but fixed on some rocking device in front of a projection screen, a method which may have been used simply to save on location expenses but which, once again, had a felicitous effect: the imperfect coordination of the car and the projected scene’s motion enhanced the sense of vertiginous instability (and may this effect not have been one reason Alfred Hitchcock, the director of “Vertigo,” also favored the liberal use of rear-projection in his films? And is it not because I find Hitchcock’s works too reminiscent of these school films, of their saturation with dread and airlessness, that I have always found it rather hard to appreciate it?)

No doubt it was also mainly because of budget constraints that none of the disasters which forever loomed in these films, none of the traffic accidents which seemed certain to occur in consequence of such atrocious decisions as backing a car out onto a road, or not stopping at an intersection on your bicycle, ever came to pass or were ever seen to happen on the screen, the fateful sequence always being interrupted before it reached its climax; although it is possible that the filmmakers also did not want to shock their audiences of school children, nor, conversely, make their films accidentally entertaining as the children learned to take a perverse pleasure in the crashes and their messy aftermath. Whatever the case, these withheld accidents may have deeply frustrated one viewer, the writer J. G. Ballard, who would go on to compose “Crash,” a novel which later was turned into a film that is unlikely ever to be shown in a school library, for it amounts to an ode to accidents in which, as if in rebellion against the too-wholesome world of the school films, and on the subconscious implications of their coitus interruptus-like deflections of the climatic accident, kinky sex is married with car crashes and the damage that result from them. Ballard does, through his narrator, go so far as to allude to the films, and to the unease which they inspired (though he appears to have seen them not on a school library’s roll-down screen but on television): “Like everyone else bludgeoned by these billboard harangues and television films of imaginary accidents, I had felt a vague sense of unease that the gruesome climax of my life was being rehearsed years in advance, and would take place on some highway or road junction known only to the makers of these films.”

Of course, that the gruesome climax to which Ballard refers never quite took place in the films made it, like all unseen monsters, like everything whose name cannot be spoken, seem all the more dreadful, all the more potentially gruesome. But as you watched the films, all normal life, no matter how tame, secure, wholesome, seemed the most fragile of contrivances, precariously balanced, barely controlled, with a dreadful, shattering accident waiting around every corner and curve for only a moment of inattention on the part of a single person. Normal life, the films seemed to tell us, was no more than a thin set-up for horror and doom, and the brighter and more innocent it seemed, the more portentous of nothing good. Made at the height of the so-called Age of Anxiety, the films were very much products of that age, borne of and also punitively breeding the emotional state most characteristic of it.

It was, in any case, always with relief that we saw the lights come back on, that we returned to an everyday life that was in full color and felt so much more solid and accident-proof as to seem capable of denying the films any lingering effects on our imaginations. We certainly did not spend the rest of the day cowering from the prospect of accidents, regarding with anxiety any object in motion, trying to be as stationary as we could. But that the films’ anxiety had nevertheless implanted itself in us became evident on long road trips in the back seats of our parents’ cars, as we found ourselves too quick to discern moments of peril on the road and, at those moments, lost faith in our fathers’ ability to negotiate them. And when we heard of friends or acquaintances who had been in serious accidents, we would coat the real catastrophe with the buildup of dread left in us by the films, as if the real accident were the long withheld conclusion to one of those films, the coming out into the open of the horror which the film only ever hinted at, the gruesome climax which Ballard’s narrator thought the films had been rehearsing. Further putting us in mind of the films, for it seemed to mimic them, the oral accounts of real accidents were often dreadfully garnished with details of the everyday actions or sayings which had immediately preceded the accident. Horrified, we would become superstitious about not repeating those sayings or doings on our own car journeys. I would never, for example, announce that a particular destination was in sight, because those happened to be the last words spoken by the mother of one of the most attractive girls in our apartment building – her last words before, at a highway intersection, a speeding motorcycle plowed into the side of their car, instantly killing the girl’s parents and costing her an eye, among other injuries.

Of course, further contributing to the films’ power to disturb us was the very problem which they were, curiously, meant to address: the fact that the traffic accident was then still the chief horror of modern life, the most obvious dark side of its speed and convenience. The possibility of a car accident was ever present in our lives then, and we never saw someone off on a road trip without a sense of apprehension. It seemed to be how celebrities were most likely to die dramatically other than by their own hand. James Dean, Jayne Mansfield, Jackson Pollock all died in car crashes a few years before my birth – and Albert Camus, whose novel, L’Etranger, influenced my sensibility, behavior and life for decades after I read it at 16, similarly perished only the day before.

But showing us those films by way of preparing us to be safe drivers when we came of age was akin to showing nervous troops about to be shipped into combat films that dramatized the many ways in which they might soon die or be maimed. And this dubious and crude psychological technique extended to the press. Newspapers of the time reveled in publishing gruesome photographs of the wreckage at traffic accidents. And at the traffic department offices where, in the country of my childhood, we might go with our parents when they had to pay a fine or obtain a license or number plates, what we had to look at on the walls as we waited were larger, more crisply detailed, glossy forensic photographs of the mangled remains of vehicles, the model that most often was featured, or the one that most impressed itself upon us because it was almost always the most badly wrecked, thanks no doubt to the fact that it had no engine under the hood to prevent that hood from crumpling on impact, being the Volkswagen Beetle. Not surprisingly, most of us seemed to regard the VW as a deceptively benign-looking deathtrap on wheels, and when we watched the comedy “The Love Bug” we found it rather difficult to share in the sentiment of its title. In my immediate community, in which Portuguese was also spoken, we pretended that the VW initials stood for Vira Voltas, or Topsy-Turvy, because the car did have a reputation for easily tipping over on sharp corners. Its very antithesis was the equally unique Citroën DS, with its hydropneumatic self-leveling suspension. The Citroën DS – the car in which Roland Barthes discerned spiritual qualities and which was nicknamed the Goddess – was then considered the safest car to drive, a claim validated by the fact that we never saw its gorgeously unconventional UFO shape – the brainchild of an Italian sculptor – dreadfully crumpled up in accident photos.

And both the newspaper and the traffic police photos were, like the films, in black and white. The world of the traffic accident, of the road horror, was, it seemed, a black and white one, as if the color drained out of life in an accident as blood drained out of the accident’s casualties. And it was possibly the proliferation of color photography, with its vividness, that finally alerted the authorities to just how gruesome accident imagery was, what an assault it must constitute on the sensibilities of the young, how too primitive and brutal a deterrent.

Oddly, once I began driving myself, I never once felt haunted by any of this – the school films, the accident photos, the insecurity I used to feel in the backseat because of those films and photos and the accidents that we heard about. What the films had chiefly relied on for their vertiginous driving effects, I then realized, was, first, our childish ignorance of what driving was truly like and, second, a variant on a certain psychological phenomenon to which, in our ignorance, we were especially susceptible, a phenomenon most commonly known in the guise of backseat driving, a peculiar form of anxiety rooted, as most forms of anxiety are, in exaggerated, unnerved perceptions of impotence in a danger-laden environment. As children we are, of course, impotent before almost everything but trust that the adults who supervise us have it in hand. The films upset that faith, especially since they were supposed to be authoritative, essentially nonfictional, school-sanctioned depictions of what normal life, and driving, was really like, how much more perilous than the adults who truly cared for us had given us reason to believe. We did not fully understand, of course, that the films were simply trying to drive home a point. They were not out to change our entire feeling for life, to show us what life was really like beneath the illusions and deceptions that comforted us. These were not existential films, even if they did more or less coincide with, and conceivably were at least remotely influenced by, not only the Age of Anxiety but the age of existentialism spawned by Camus and his friend Sartre – Camus who might have benefitted from exposure to these films, if they did indeed have any accident-prevention value.

The films’ skewed perspective on life, if skewed it indeed was, was completely righted for us only once we ourselves had learned to drive and saw how confident and in control, how potent, how protected, one feels behind the wheel. I felt safe even when driving at breakneck speeds or (the moments that most terrified me on car journeys as a child) when overtaking slower vehicles by moving across the broken line onto the oncoming traffic’s lane (single lane highways were still the norm when and where I began driving) or on a vertiginously high bridge or mountain pass. I felt confident of my control of the vehicle, confident of my ability to discern or anticipate hazards. Just as real life, especially in its most innocent moments, rarely felt as ominous as it did in those films, so the act of driving, I was relieved to discover, rarely felt as perilous. The films had left that out: how secure a driver feels behind the wheel when a car is working as it should, as if it were a mere extension of your body, one that seems only to add to the body’s power and invincibility rather than to render it more vulnerable and at peril.

Of course, all this confidence is founded on illusion, as seems obvious when you rationally consider that the human body is not equipped to race over the ground at speeds so much in excess of its own capacity: nothing good can happen to the human body should something go wrong at those superhuman speeds, when the armature of the motor vehicle will become as much peril as protection. It then seems astonishing that even frail grandmothers are able to do it without hesitation.

The films intentionally militated against heedless confidence, against trusting on benign outcomes to reckless behavior, against, especially, children’s natural inclination to think themselves beyond serious harm, essentially immortal. Children are gluttons for illusion, and we detested those school films because they proffered quite the opposite, not comfortable, entertaining illusion but bleak demonstrations of how unbearably ominous and perilous not only traffic but normal life could be, how much a cause for everpresent anxiety when not seen through a thick colorful veil of illusion. But so effective were they that we could not but reject them, just as, throughout our lives, we continue to fend off the utterly disillusioned view, perhaps correctly afraid that we will be unable to go on living without illusion’s help to shore us up.

I, for one, continue to feel safer zipping along rather than cruising. I believe greater speed forces me to concentrate on the road, lends a certain smoothness to my decisions and the car’s actions, and gives me the sense, no doubt at least in part illusory, that I can more quickly anticipate and avoid obstacles and hazards. And greater speed can also create this confidence-boosting illusion: because you are frequently passing other vehicles, you feel superior to other drivers, more masterful, more in control.

As I speed along in defiance of those school films, I am even inclined to believe that most accidents on the road are caused not by drivers like me but by those who drive as if they had been overly intimidated by similar propaganda, who dawdle uncertainly, rattled by every car that speeds past, spying danger everywhere, full of distrust in themselves, their vehicles, and everything in motion around them, knuckles often turning white on the steering wheel, who act, in short, as if permanently trapped in the harrowing reality of those films. By their timorous excess of caution, they seem to vertiginously invite the very thing they are guarding against.