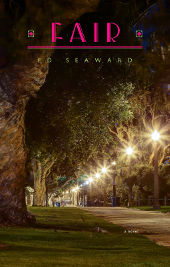

Ed Seaward | Fair | The Porcupine’s Quill

Fair, the first published novel from Canadian author Ed Seaward, offers the reader a warped pilgrimage into the underbelly of Los Angeles, trailing in the footsteps of lost soul, Eyan, as he flies low under the uneasy influences of pint-pot street tyrant Paul, and a wandering, dishevelled scholar, known simply as ‘the professor’.

Fair, the first published novel from Canadian author Ed Seaward, offers the reader a warped pilgrimage into the underbelly of Los Angeles, trailing in the footsteps of lost soul, Eyan, as he flies low under the uneasy influences of pint-pot street tyrant Paul, and a wandering, dishevelled scholar, known simply as ‘the professor’.

Eyan’s magic cloak of social invisibilities—solitary, homeless, jobless—ostensibly makes him an ideal flaneur in the City of Angels’ sinister reverse face. His Los Angeles manages to feel at once limitless and claustrophobic: he meanders through sticky days and danger-filled nights at his own helpless pace. His way markers are usually the people he encounters, or counts on encountering: the coffee vendor on the boardwalk; the friendly waitress at a local diner. His own personal history is revealed in short, painful showings: his complete tooth lessness, at the age of twenty, is explained by a bout of violence from one of his mother’s boyfriends; we learn that his mother and sister abandoned him, as a teenager, after he chanced upon them performing a joint act of prostitution. The one protective figure in his early life, Larry, another of his mother’s boyfriends, also disappeared early on: “Eyan always knew Larry was not long for Mother”.

The professor—half father-figure, half spirit guide—and Eyan are brought together by Eyan’s childhood friend Marc, who himself lapses into street living, fuelled by substance abuse, for a time, before being spirited off by his family to ‘the clinic’. Despite his own street lifestyle, the professor is, somehow, mysteriously solvent: “The myth of the professor and his money: hidden somewhere and, from time to time, the professor leaves, walks and retrieves a little of the money, then returns”. Things settle into a cautious routine as Eyan and the professor become accustomed to one another’s company. The symbolism and structure of Milton’s Paradise Lost, which the professor begins to read to Eyan, loom large throughout the narrative, which pointedly “starts in the middle”. The professor pontificates; Eyan makes desultory notes: Omnipotent, Adamantine, Darkness visible, as he’s told, approvingly, “you do not have the worst vice, the vice of over thinking.” The professor, on the other hand, lives up to the stereotype of his name, spouting gobbets of history alongside his parsing of the poem: “A hippodrome was an ancient Greek race track where they held chariot races, like the Roman Circus” […] “Should I tell you of Messalina, Eyan? Maybe not. What need do you have to know of the wife of Claudius?” […] “In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries […] great battles soaked red the fields of England, and men caused death with broadswords and longbows”.

Speech, particularly when the professor is around, always seems to take on this slightly convoluted register: Marc says “My friend has not been to the sea in so long that we declared a need for a pilgrimage and here we are with you.” Ponderously, the professor answers: “Or perhaps it is a quest […] A quest for the boy of whom Marc forever speaks.” Marc appears again to jumpstart the plot by introducing small-time crook Paul—another old classmate—who, under threat of violence, co-opts Eyan as a drug mule. Peripatetic and often invisible, Eyan has his uses, trudging obediently about the city on this new business, delivering parcels of drugs to one of Paul’s small army of droogs, “the brackish boys”. Between drops, he returns to the professor: they eat hamburgers at a friendly diner; they rest in the heat of Skid Row, alongside most of the city’s homeless population; they continue through Milton’s verse. Eyan ultimately begins drawing parallels between the poem’s fiery chasms, and his own personal and literal landscapes, peopled by demons and lost souls.

Throughout all of this, we veer between a limited and an omniscient third-person perspective. Eyan’s own thoughts, once they’re loosened from the professor’s cerebral posturings, are pointedly uncomplicated. Encountering two women, “Eyan wonders if they will be allowed to ride the Ferris wheel or the carousel or if they are too fat. Maybe they don’t want to ride those rides though. Maybe they want to eat red candy apples and blue candy floss”. If the intent is to emphasise Eyan’s almost total effacement by the wicked streets, the result is almost too effective: even in this slight novel, as its central character he’s often subsumed by the wandering plot. Although he guides the narrative, his character can sometimes read as resistant to interiority. We swirl in the slow current of his thoughts, “a timeless sack of memories”, which return repeatedly to the same points of safety—Larry’s easy kindness; sitting with Marc after school, watching cartoons. We don’t penetrate much further, and if this is a device meant to convey Eyan’s cultivated detachment, his larger, protective recoil from any attempt to understand him, or to harm him, it also has a perhaps unintended effect of muting our impulse to care about him. That would be a clever indictment of the reader, a textual mirroring of the same trap of societal indifference to which Eyan falls victim.

The tone of the writing seems to aim at a kind of sparseness, a poetic distillation of the language into one elegant register. Though as Eyan wanders again between Skid Row and the Boardwalk, as we’re confronted repeatedly with Paul and his cronies, as Eyan’s dulled thoughts shade into the professor’s florid monologues, the effect is occasionally more monotonous than incantatory. The book’s ultimate messages are in some ways straightforward, with Eyan a symbol of all the harmless individuals who slip through the cracks of a shamefully uncaring society. But the conclusions about who, or what is to blame for this are less clear—if there are indictments, they feel personal rather than structural. Fair ultimately leaves its readers to mull over the formidable Miltonian parallels around sin, fall, and redemption, and draw their own conclusions.

by Phoebe Walker