Trí báis atá ƒerr bethaid: bás iach, bás muicce méithe, bás foglada.

Three deaths better than life: the death of a salmon, the death of a fat pig and the death of a robber.

(9th C triad: Meyer, Triads, 12§92)

Srahederdaowen is exactly as the native tongue would have it – sraigh idir dhá abhainn – a fertile bend of land, or a natural sheep pen, between two rivers. Its western apex, a triangle of rich green ground, clumped with rushes and profuse in season with field mushrooms, is generally known as the Junction, though some call it Mac’s Island where the rivers meet. This townland of less than three hundred and fifty acres stretches roughly two miles up to the swing-bridge at Tarsaghaun Beg but only half a mile up the Owenduff to Baltaí Mór, where it meets the townland of Owenglass. According to census returns, its recorded population between 1841 and 1911 was never greater than seven, a figure not exceeded in living memory. There is the ruin of just one dwelling here – Clearys’ – and no evidence of other buildings.

At the Junction, Tarsaghaun empties into the Owenduff. Here begins the first great solitude on the rivers as one advances upstream, for once Lagduff is left behind no other living house is met on either stream for the next three miles. This was the only part of the system we knew as children, bar the Bridge Pool at Srahnamanragh Lodge and the estuary below. Our father liked nothing better than to come up here to fish a dropping flood. The rights to fish the Shean beat of Owenduff and the left bank of Tarsaghaun are held by the Craigie family of Shean Lodge, but my mother’s father, The Judge, seemed to have a gentleman’s agreement to fish it whenever he pleased, and that may have extended to his son-in-law. My elder brothers might fish with him – never my sisters, though one liked to play his gillie – and if there were still room in the car and no better offer pending – a trip to the beach or a visit to a neighbour – us younger lads might pile into the boot of the Opel Caravan in our wellies and ‘head up’. Passing John and Katie Keane’s, then John Mike Conway’s, houses we often visited, the road was familiar as far as Mrs O’s. The next mile, through flat, sloping bog devoid of houses until Marty Murray’s, was more exotic. Approaching Murrays’ I never failed to scan the unseen river, find the shell of Eric Conway’s burnt-out house and imagine again the five-year-old boy jumping from the upstairs window onto the roof of the porch.

An ancient, stony track leads to the Junction from Murray’s at Lagduff Beg, called the Muígnagúnla Road after the stream it crosses half way along. My father’s car could be risked at a crawl almost its entire length. The shock of the scrape and the thrill of the bump would fizz in the roots of our hair, but that Opel, and later the Sunbeam Rapier, later again the Singer Vogue – sewing machines on wheels that latter pair were – squared up well to the abuse. The low-slung, maroon Zodiac passed down by The Judge when the Opel went to pasture wasn’t so fond of that road and we’d have to get out and walk the last half mile. From where we parked, this track continued down into and across the Owenduff, exactly at its present confluence with Tarsaghaun. Back then that junction was fifty yards downstream, at the neck of Roger’s Pool, or Ailt Rúaidhrí, and where it is now was called the Cartling, a pair of fords for horse and cart – first over the Owenduff, and then Tarsaghaun – to McHughs at Lagduff More (later bought by ‘The Germans’, now HQ for the Office of Public Works at the National Park).

Thirty yards upstream from the Cartling on the Owenduff is another ford, called the Cartway, still in use by quad today. This provided a crossing by horse and cart, not just to the Clearys, four hundred yards above on Tarsaghaun, but also to both Moran households way up the Owenduff in Owenglass. It also gave access to neighbours downriver who came here to harvest rushes for their roofs, for thatching pits of potatoes and reeks of hay, and as bedding for their cattle. Wool from sheep sheared in sraighs or ‘yards’ along the river was still being taken home this way by cart when we were small. Close examination of the Owenduff all the way up to Shean reveals several of these cartways, allowing horses with carts to cross over and back the river, that they might always keep to the good ground of the sraighs.

It was on those endless days at the Junction that the conversation began some of my siblings and I are still having with those rivers. A world onto itself was discovered – its sounds, smells, shapes, colours, vistas, light and shade, flora and fauna, midges, rusty puddles, breezes, sudden showers and other caprices of weather – all growing into a permanence that has outlived all the other fixtures of our youth. Strangely, despite the company, my recollections are strong on solitude – wandering, wading, collecting stones from the river bed, annoying frogs, feeding insects to the sundew and watching their work in awe, matching skylarks to their songs, following falcons or hawks through squinted eyes, gathering mushrooms on strings of rush. I picture each of us too young to fish, wandering off alone to resume his dialogue with the water, earth, stone, jacksnipe or rush, each according to his fancies. To this day, arrival at the Junction brings on a wash of gladness, as though entering again a simpler, cleaner world. Casting a first line out, or wading in, one slips back on the robes of a pure, eternal life.

On the right bank, between the Cartway and the concrete footbridge, thirty yards upstream again, a cutting in the turf bank provided shelter when the heavens opened or the breeze fell off and midges came to plague us. This was a straight-walled cave, roughly two yards high and deep, that my father liked to call the ‘shepherd’s hut’ but was, in truth, the sod-house of Jack McHugh, charged to watch both rivers at the Junction. For a few pounds a season, water-keepers along the river, each with their own two or three pools to keep an eye on, were expected to spend the shorter nights ensconced in tiny huts, and to light a small fire to show they were within, sufficient deterrent, it was deemed, to keep the poachers honest. More often than not the fire was lit and the sod-house abandoned, though stories abound of teams out poaching surprising the man within and blocking his exit with a door leaf, or some other obstacle, rendering him ‘half-smoked’ when the pool was done. Jack used sometimes keep his Honda 50 in that hide. Shepherd’s hut, sod-house or bike shelter, this little nook was a blessing in adverse conditions. From here I recall one day watching my father fishing Poillíneascannaí, the pool just below the concrete footbridge, and seeing him get so meithered by midges that he put down his rod, stripped off all his clothes and dipped himself in the stream, dressing again quickly without drying, all the while blowing pipe smoke around himself as if that would offer relief. In our hide we weren’t immune to midges, but at least we had two hands to fend them off, a luxury not afforded the focused angler. That hide has since deformed and more than partially collapsed, but those of us who know can still discern it.

A dry, breezy day was best of all, when the midges were kept down and we could wander freely. These conditions suited our father too and kept him hopeful, even if water was low, the breeze curling the surface of the water to a ripple, masking his line from the fish. He had great regard for the fish’s sense of sight but never seemed to mind us making noise, as long as we kept back from the bank. ‘If fish could hear as well as see, fishermen would never be’ – we heard that more than once. I would often lie on the bank below the pool, maybe thirty yards downstream, leaning on an elbow and chewing a rush, and watch him. The casting I found somehow enchanting (to this day I can stop to watch a fly being cast and remain in trance for ten or fifteen minutes). The image of my father casting is particularly strong from Poillíneascannaí, him in thigh-waders, shades and cap, the concrete footbridge behind, the blue-grey bulk of Corsliabh rising behind that again, his silk line lifting with the softest smack from the black water along the near bank and whistling faintly back upwards over his shoulder until the fly reached its furthest rearward point, the entire line stretched out in a long thin, glinting stripe, angled just enough to clear the turf bank, the rod then inflecting oppositely with a movement of the wrist, the jerked line spraying mist, and the fly, just as it seemed to pause in mid air behind, tugged forward again, surfing the wave of the unfurling, rolling line until it reached its furthest point ahead, the long lit stripe suspending a yard above the river until it dropped ever so gently and kissed the water.

Another vivid image from that pool is the meitheal gathered one fine summer’s day in the early 1970s, to rebuild its weir when the river was down to its bones. John and Manus Keane, Tommy McHugh and Tony Conway were among the men, and my father, a dentist by trade, at the helm of operations. Great rounded boulders were levered and lugged into place by two and three strong men at a go. By evening an impressive dam spanned the stream like a grotesque set of drooling lower dentures, and the rejuvenated pool resumed a former elegance. That weir still holds water, after nearly fifty years of heavy floods, though recently one of its largest molars has slipped away downstream. Many a salmon has been induced to linger above that weir and, short though it is, Poillíneascannaí is a lovely pool to fish, the fly swinging round from the fast water under the right bank into a deep back-eddying basin at your feet. Of all dark pools on the Owenduff, this one seems to me the blackest.

Whoever built the footbridge at the top of Poillíneascannaí, that it stands yet as a monument to their labours is amazing. Flood after roaring flood has battered and drowned it. Many of its reinforcing irons have been exposed by eroding concrete but it still feels solid as the rock on which it was built, great slabs of ‘skelped’ granite, pitted steeply in valleys with sharp ridges (much like the Bridge Pool below at Srahnamanragh), a feature which may have given the pool its name, Poillíneascannaí – Pool of the Knives. Yet the bridge is in no way blocky. Its piers are thin and tall and its span narrow. In a big flood, the torrent rears up on the middle pier and your palpable mortality assails you as you hurry on across. In a huge flood, the entire bridge becomes a weir, the water pounding through its open sides and bellying over its top rail. Not many have witnessed this but, among them, Michael Martin Conway has seen it more than most. Tens of thousands of sheep he has put across that bridge, in strictly single-file. On a good day, over an hour could be spent getting a hundred head across. Add in lambs and high water and you may set aside the day. The lamb will invariably turn back or leap forward in search of the mother and one or the other, or another again, will find itself careering downstream in white water, often not making it to shore until the Junction far below is reached. And if not by then, good luck to them. They can’t be run after for fear of those left on the bridge.

Nearly fifty years ago the novice Michael Martin was moving two hundred head over. He had two dogs with him. Water was high. On his way to the bridge he exchanged courtesies with my grandfather at Poillíneascannaí. The Judge was full of the joys, having just then landed a storming springer. The sheep crossed without complication and were pushed on upriver. It was only when he approached the one ruined house of Srahederdaowen that Michael Martin heard roaring from behind at the bridge. Hurrying back, he ordered the dogs to hold the sheep. But only one dog could he see. The Judge’s bliss had evaporated and he was flapping like a furious semaphore towards the missing dog dragging a half-devoured salmon, in silhouette, over brow of the bog. There was little to be done but retrieve what could be saved and apologise. And then bask in the inner glow of having once more scored against the toffs.

An even better result was achieved by Michael Martin’s sister in the same pool, not long afterwards. The angler now was Des O’Rourke, sergeant of the district and no slouch at all in his pursuit of poachers. She was returning from the sheep alone, the menfolk all busy at home with silage. Passing along the sraigh above the bridge, she stumbled on a grilse secreted in the rushes, a fresh six-pounder. Obeying instinct if nothing else, she hid the fish inside her jacket, crossed the bridge over, bade the sergeant good day and inquired if he’d met any fish. ‘Not a one’, he replied, ‘but isn’t it a lovely day all the same?’ The silage makers ate like kings that evening and the following day the girl’s proud father, Mike Anthony, was genuinely sorry not to be of any more help to the sergeant with his inquiries at the door. Perhaps it might have been a wily fox?

That ruined house of Srahederdaowen, a quarter mile up Tarsaghaun from the bridge, was known as Martin Denis Cleary’s. A long two-roomed, unplastered, stone thatched cottage, it had a lime kiln and quern stone within a garden banked against floods on the river, twenty paces from the door. Nothing now remains of mortar in its walls and the impression it gives today is of struggling to stand steady. Most of the upper gable stones lie strewn about the grass, many already buried or overgrown. Those remaining in the walls vary greatly in size, showing no obvious pattern in their arrangement, all their corners weathered. Their colours differ radically too, so that each wall is a mosaic of flat rocks, random as to size and speckled every shade from white to ochre and grey to amethyst. While most of the stones have at least one flat face, only the lintels seem specifically worked for their purpose, redundant now with all above them fallen. The chimney too has tumbled. Within the garden banks the grass is greener to this day, though Clearys’ ample wind-bent cherry trees, once the late summer fillip of angler and herd alike, are now usurped by wind-bent sycamores. Forsaken, this homestead huddles exposed and tiny against the great scrum of Slieve Alp and Marafann, Corshliabh, Tawnasheffin and Scardaun. Picture postcard possibilities notwithstanding, it’s hard to pass without reflecting on the elemental life that must have been the Clearys.

The handful to have told me of being inside this house each called it one that none could pass without stopping in for tea. My mother, as a girl, spent many an afternoon here, her father fishing the riverbank outside, or the Owenduff a quarter mile to the south. Martin Denis had the softest speaking voice she ever heard in a man and spoke to her in English when she couldn’t grasp his blas. His wife, Molly Keane of Muingnaholloona, was famous for her looks and for her cooking. As a young woman Molly cooked at Shean Lodge. It was there she met and nursed Martin Denis, brought in from the river one evening shot in the face poaching salmon. How he subsequently became bailiff for both Lagduff and Shean fisheries may be a testament to Molly’s powers of healing. They had one daughter, Mary Kate, also famously beautiful, who only recently died in England at a big age.

Their smallholding bears the traces yet of self-sufficiency. Lazy beds of different widths suggest variety of crop and the quern stone that they ground their own cereals. The sod walls surrounding these gardens were once much higher, the only barrier then to hungry livestock. With not a trace of limestone in the parish, the lime kiln was for burning seashells, brought with horse and cart from the shore of Tullaghaun Bay, four miles to the west. Powdered shell and seaweed were fed to all the crops, and maybe too the cherry trees, which would have needed every help to prosper in that place, yet still were ‘red with cherries every year’, as Fred MacManamon, gillie for decades at Shean Lodge, remembers. ‘We used stuff our pockets with them heading up Tarsaghaun’. No doubt the cherries were preserved in jams to sweeten the long winter evenings and it’s hard not to imagine that one as attuned to the river as Martin Denis would not have had at least two half whiskey butts hidden away, lidded and filled with salted salmon and sea trout soaking in brine, harvested by trammel net, or caidgeal, not a stone’s throw from the house. His nearest neighbour upstream, Pat Sweeney, the bailiff for Tarsaghaun, apparently did. That is, if Eric Craigie is to be believed, to whom it is claimed he proudly showed the stash while in his cups.

In Martin’s gift as bailiff was the dispensing to anglers of fishing licenses. It never failed to amaze Fred that, though tucked away on Tarsaghaun, with no recourse to phone or telegram and little to local gossip, no sooner would a guest dock at the lodge but Martin Denis would land in that evening with his book of licenses. He’d have walked the four miles upriver with his home-made torch – a jam jar into which a halved spud had been laid, flat side down, a hole bored in it to take a candle, the lid punctured to provide air and to take a wire handle – the standard issue lamp for crossing the bog at night. But they never could tell how he knew when to come. Did he have an uncanny eye for smoke in a windy sky? The local system of coloured cloths laid out on bushes, relaying simple messages over stretches of bog, may have been at play here. But even still Martin Denis would have to climb to the hill they call The Árd with the Green Bush to catch a glimpse of Moran’s in Owenglass, sadly also now defunct, or his cousin Marty Joe Cleary’s further on upstream, who in turn would have to scale a height to see what signal Keanes or Walshs made about their neighbours at the lodge. Easier to imagine it being down to instinct, a nose for things, a talent useful in his former trade.

Also in Martin’s gift was the killing of pigs at Christmas, visiting neighbours in turn to do the dreaded needful. Fond children, lonely for the creature they had fed and petted and cuddled and admonished, took tearful leave of it before setting out for school. So gentle was his approach, so trusting the pigs, that the inevitable squealing lasted only seconds. Martin Denis would simply slip outside, the shrill cry would sound and he’d come back in wiping his blade. This service he performed from Tarsaghaun More to Srahnamanragh and often further afield. The pig would then be laid out on the table, washed in hot water and shaved, before being hung from a ladder in the kitchen and cleaned out, the blood drained for puddings into pots. Nothing went to waste. Young Pat Gallagher, told the bladder could be used to make a football, waited for it eagerly, washed it and inflated it, but could make neither head nor tail of it. He ‘never did any kicking with it anyhow’.

As a boy of seven or eight, Pat went with his mother to give the Clearys a day at the turf. As they were leaving in the dusk Mary Kate delighted him with the surprise gift of a Rhode Island hen. He tucked it carefully under his oxter and minded it with his life forever after. On another occasion, when he and his father were passing down, after leaving sheep in Díogan valley, they found Martin Denis out on the brink of the river gazing at the sky, and were ushered in for the tea. Molly was below in the bed at the end of the house, sick with a cold, so they went down to pay their respects, only to find her sitting up in the bed, content as a lord, only dying for the chat. But Pat had no heed at all on the woman, having eyes only for the beautiful velvet curtains surrounding the bed, a floor to ceiling canopy. Did this accessory to her mystique have perhaps the extra job of keeping off the midges? That canopy makes an appearance in Eric Craigie’s account of Martin Denis’ wake, in Irish Sporting Sketches: “He was laid out on snow white pillows on a big canopy bed and pure white linen covered his remains.” This is a tribute as much to Craigie’s memory and imagination as it is to Martin Denis, who had sold the house a decade before he died in Ennischrone, where he was waked before his remains were buried in Bangor cemetery.

A generation after Pat, Michael Martin Conway, as a boy, stopped in for tea with Mike Anthony, coming from their sheep on Sliabh Alp. This was not long after Clearys’ house (then known as MacManamons’, to whom it had been sold – hence Mac’s Island) had been closed up, but it was still in good enough order and the thatch in fair shape. They lit the fire, brought the crane and kettle back to life. His father had been great with Martin Denis and was comfortable, but young Micky Martin remained on edge, watching reflected flames dancing in the holy pictures, bursting to leave, feeling all the time he was being watched.

Not many years after that meitheal at the weir in Poillíneascannaí, towards the end of the seventies, an intriguing new house sprang up near the Junction, across and down the Tarsaghaun from Cleary’s ruin, on the site of Jack McHugh’s old cottage. Big and modern, with windows in the roof, it still answered to being long and low. Built by a reclusive German couple, Holger and Gertrud Moldering, it sat on the edge of forty-three acres bought from another McHugh, of Achill, who had bought it from old Jack and who, not long afterwards, so the story goes, disappeared into America. Our old friend in Srahnamanragh, Mrs O, was beside herself with curiosity. ‘Well who the bloody hell are they?’ She had it that these blow-ins were so secretive they’d imported all their building materials – and their builders – from Germany, that they only left home once a year to buy supplies they couldn’t cultivate themselves – such as rice, salt and matches – and that the only bread they ever ate was black. ‘And how much do you think the bleddy range? (pause) Seventeen thousand the range. Well, my you God tonight!’ In the many visits I made to the Junction during the Germans’ time there, a constant sight across the rivers was their five Doberman Pinschers, or Schnausers, silently patrolling the electric fences. ‘They’d tear you apart in five minutes.’

As I never met either of the Molderings I could never satisfy Mrs O with news. Nor could Willie the Post. Others knew them better. Mike Anthony sold them lambs. Mary Murray’s curiosity could not be stopped at the gate. She ‘visited them regular, because they were full of information’. Bea MacManamon found it miraculous to see their herb garden in the glasshouse when she visited with a friend suffering from cancer. A suitable herb was found and chewed, intoxication suspected and an increase in wellbeing noted. They were then shown the flies kept to make some change on the herbs and the frogs kept to later dispose of the flies. In all my conversations about the Molderings since they came, the most word used to describe them was ‘peculiar.’ They were ‘funny in their ways. He’d go out to the garden and bring in a plant and make soup with it, and you’d think it was only a weed. To us it was a weed’. Among the many peculiar things the Germans were known to do were milk sheep, make their own cheese and yoghurt, butcher their own animals, feed their goats to their dogs when they got old, rest daily from two to four, grind seaweed, make wine and elderflower champagne, grow herbs for curing cancer, generate power from the wind and move rivers.

They were certainly self sufficient to a high degree. Visible from Ailt Rúaidhrí was an extensive vegetable garden, a steamed-up glasshouse, Kerry cows, Soay sheep, goats, hens, ducks, geese, all manner of poultry. And they clearly thought highly of privacy. Half a mile along their driveway to the Bangor road, they’d installed an electric gate, post-box and intercom, so not even the postman got a glimpse of their interesting lives. Handling their back gate to the river, set into the electric fence, sparked an alarm that lit a red light in the house. Which is not to say that they had no interest in others. Rare visitors noticed a mirror in their kitchen, angled to see whomever might pass up along Tarsaghaun, and their top window was a veritable watchtower, with binoculars to the ready and an ever-present telescope on legs. ‘He could see nearly into Shean’.

Holger, they say, was fond of the rifle and not just where dogs and foxes were concerned. A pair of Fred and Bea MacManamon’s dogs followed a bitch in heat to somewhere near his land, and didn’t survive his aim. On one occasion, he offered to shoot Marty Murray’s trusty sheepdog, with whom a healthy mutual hatred had grown up, and to replace it with a Schnauser pup. On another, a guest at Shean Lodge betrayed an interest in seeing the Germans’ pedigree goats. Bea, who had a line of contact with the Molderings, set up an appointment for him to visit. The fishing was good that day, though, and Bea’s husband Fred, the gillie, had to be sent to the river to remind the man that ‘time is time to these people’. Arriving late with a friend, the angler found Holger livid at the gate, his schedule for the day in ruins. When the friend alighted the car he was told that an appointment had been made for only one and was ushered back into the passenger seat. Later, when the goats were being inspected, the same man got back out to stretch his legs and feel the breeze. The rifle was instantly reached for and he was reminded, through a megaphone, that he was trespassing on private property. Holger’s brandishing of firearms was to cost him, when the Gardaí confiscated one of them, possibly unlicensed, that was considered ‘capable of long range damage.’

Michael Martin Conway worked regularly on the premises for the Molderings and thereby got an education of sorts. All would be well so long as things were done exactly as Holger specified, with zero deviation. The goats were kept for milk and cheese but when they got older and were of no more use they were fed to the dogs, resting in pens when not patrolling the fence. Michael Martin would bring the moribund nannies to the butcher in Bangor. ‘Even the goat was killed he wanted all of it back – head, offal, everything’, the head presumably to ensure he wasn’t being sold any pups. This request is reported to have led to at least one heated dispute with the butcher. But Michael Martin’s main work for them at Lagduff was cleaning out the sheds and disposing of the livestock bedding in a very particular way. Seashells were pulverised and mixed through the discarded bedding. Holger would have collected seaweed at Doughill and brought it home by trailer. There he had a dedicated drier and a grinder to turn it to dust. This was now spread on top of the heap and left to decay. All was then reeked and set on a bed of wool which acted as a screen, separating the heap from the ground below. The lot was covered with plastic and left in the garden for a year. After which time it was matured as compost, used in all the baskets in the glasshouse and spread through the vegetable garden.

Michael Martin may be the only local shown the bunker under the house, accessed through a trapdoor in the glasshouse and supposedly provisioned for any class of apocalypse. Or so Holger assured him. What he saw was a thirty-by-thirty space, its walls lined with curtains. What was at the back of them was anybody’s guess. Visible only was a chair, a table, a projector and screen, as though the impending catastrophe – nuclear bomb or earthquake, scheiβegal – might be survived on a diet of movies. When challenged tongue in cheek on the waste of valuable space, Holger, who’d put in years in the insurance industry and knew a thing or two about disaster, would only ever reply that he’d be sicher. ‘We didn’t take him too serious.’

‘She wouldn’t have been as awkward as himself.’ Gertrud had been a teacher and her English was far better than Holger’s. All knew well he understood everything, but he chose as often as not to speak through her. Things were usually easier when she was in charge. If it went raining, Michael Martin could go home for the day and still be paid. If only she were always the boss, a smart boy like himself could make a living from weather alone. Pat Gallagher would ‘take to her more easily than to him. I was never happy in his company. I couldn’t settle with him. He seemed to be here for a reason. I wouldn’t want to be along with him in the house at night. I wouldn’t trust him. I’d say he wouldn’t mind putting one away.’ Despite her relative easiness, Gertrud was not above being peculiar herself. Pat’s wife, Mary, home alone one day with a handful under nine, got a phone call. ‘Would you come and remove your calves. They are looking over at us.’ The calves were grazing the land adjoining the Germans’ but their fencing ensured that they would never get in. Mary doubted she’d heard things right and inquired politely, ‘But what are they doing on you?’ ‘They are looking at us.’ It was a textbook case of cattle over-gazing. Ever a good neighbour, Mary had no choice but to take the children with her and finally got the better of moving the cattle off, but not before her eldest had disappeared into a súmaire and nearly lost his life.

Gertrud’s parents came to live with the Molderings in a small new house they built beside their own. Her father was a tall man with a passion for constructing windmills. But he wasn’t long in it when he took ill and died. Here reports diverge. Michael Martin has it that they went to a nearby undertaker and ordered a coffin, which was duly delivered. But days then passed and there was no funeral. The undertaker became uneasy and reported it to the law. When the men in uniform showed up at the house they discovered the poor man buried in the garden. Pat Gallagher has it that when the old man took ill he went back wherever he came from and died there. But around the same time one of the Kerry cows passed away and Holger had a few men dig a pit for it. A man from Tarsaghaun happened to be passing down at the time, on his way to Bangor, where he found speculation rife in the pub that the old German had died. ‘He did surely’, said he. ‘I know for a fact he did. I seen them digging the grave when I passed down.’ With the result that news spread quickly, and the story finishes with Sergeant O’Rourke and the undertaker calling to Lagduff to disinter a cow. ‘To this day some of them thinks he’s buried up there yet’, says Pat, insisting that he wasn’t. There’s gravity in Michael Martin’s final word, ‘Well I actually dug the grave. I didn’t even know the man was dead in the house at the time, but I knew what I was digging and I said nothing’.

One evening in the summer of eighty-nine the Molderings invited over his father, Mike Anthony, to view some lambs born of the sheep he’d sold them the year before, knowing he’d be interested. Together through the kitchen window they admired the beautifully conditioned lambs gambolling around the duck pond. Alas, that pleasure was Mike Anthony’s last. Inside a minute he was dead on their kitchen floor of cardiac arrest.

A legacy of the Germans’ sojourn here is a beautiful pool on Tarsaghaun below Martin Denis Cleary’s, where they built a terrific stone weir to rise the water behind, which fed their duck pond by stream. This is a pool I can never now pass without throwing out a few casts, whenever I’m heading up Tarsaghaun. I must have hooked and lost more grilse here than in any other pool – until this week, on the eve of going to press with this, I finally landed one on its hallowed bank, and released it again with thanks. This is a great pool for sea trout too and I’ve done better here with them. Indeed, the effect of the Germans’ weir in high water is felt as far back up as Martin Denis, which has an excellent pool for sea trout right before its absent door. But this minor achievement in riparian engineering will always be overshadowed by Holger’s moving of the Junction.

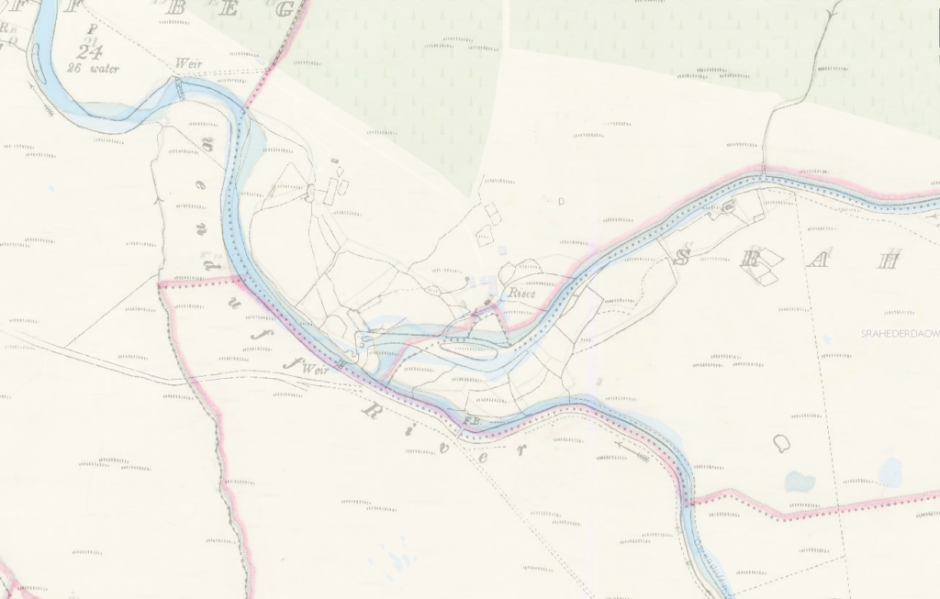

When the Molderings arrived here in 1979, the Tarsahgaun entered the Owenduff at the neck of Roger’s Pool, or Ailt Rúaidhrí (scene of the infamous affray in 1871 that saw poacher Martin Cleary shot dead, midstream, in cold blood), almost fifty yards downstream from where it does today. A fraction of their land was on the other side of the Tarsahgaun and it’s said he wouldn’t rest until he’d rectified this blunder. Strange though his ambition might seem at first, a comparison of the 1830s Ordnance Survey map with the Cassini map of 1895, shows that the junction had actually moved downstream itself in that period, that in the not too distant past the land now of the Molderings had its integrity intact, all west of the Tarsahgaun. Aware of this or not, Holger hatched a plan to put things back the way they’d been a century and a half previously. The story also goes that the man who sold him the land and subsequently vanished, had assured him that owning land on both sides of the river meant owning the riverbed too, and he could do with it what he liked. They’d hardly settled in before Moldering made the owners of both Shean and Lagduff fisheries aware of his intentions. They told him he was misinformed, the riverbed belonged to the fisheries. He wasn’t to touch it. They showed him documents, threatened law. Undeterred, he brought in big machines, a new channel was swiftly dug towards the Owenduff, fifty yards upriver from the junction, and rock armour built on each bank to protect them both from floods. Money seemed no object. It was only when the Gardaí arrived in uniform that he was persuaded to down tools. But by then the river had taken its new course. His goal had been achieved.

This change involved the softening of a bend. A consequence of this, a result previously experienced after works to straighten a stretch of the river above at Shean decades earlier, was that thousands of tons of rocks were now free to move downstream in floods. Bends provide a natural barrier to such movement, causing shingle beaches to form, impressive banks of brown, white and pink pebble and stones to the size of basketballs and bigger. Now these rocks moved freely and heaped themselves on beaches further down, becoming impermeable walls and putting massive pressure on the opposite banks, leaching out the glacial till beneath and ripping great chunks of turf away with every big, new flood. The effect on Lagduff fishery was enormous, forcing its owners, the Layden family, into banking the river with rock armour in pools and bends all the way from Pollgarrow to George’s Pool, nearly three river miles below, a project of over forty years and still ongoing. In previous decades that fishery’s owners, Chittentons, and later Hancocks, had employed locals in an annual programme of reinforcing vulnerable banks, by driving metal posts into the riverbed along those weakened strips, fixing horizontal boards to these and filling in behind with shingle and sand. This did well as long as the work was maintained but in light of recent troubles, at local and national level, relations had frayed and that was no longer an option. Besides, Moldering had just demonstrated that machinery now available could move boulders easily and quickly into position, if that could be afforded, and this was by far the more future-friendly solution. Michael Layden, as a student, spent one entire summer, shortly after the first effects of the German’s work were felt, positioning and filling gabions along the banks. During a weekend interlude, while he let his hair down at a jazz festival, one flood washed his summer’s work away.

Another consequence of the Tarsaghaun move has not escaped Michael Martin – confusion among its salmon. He has seen fish work their way up Tarsaghaun in low water, only to change their mind and snake back down to Owenduff, ‘splashing over the stones.’ Their navigation systems may take more generations to adjust. And this may explain the productivity of the new pool created by the German, called the New Junction, between the present confluence and the old one at the neck of Roger’s. Big salmon are known to give pause under those rock armours. Only last summer a twenty-one pound fish was landed here on rod and line. But that was only a sprat towards the thirty-two pounder Michael Martin saw coming out of that pool ‘on January 26th, 1990, a Sunday morning’. He dates it precisely (if wrongly) because it was himself liberated that fish from the river. He’d been there the evening before with sheep and thought he’d seen a big wave. It was no otter. All his experience told him a special fish was in the pool. And though next afternoon at one he was down to play a football match in Breaghfy, he couldn’t help but return in the morning early on the Honda 50 with a friend, a sceptic who’d never fished before. Michael Martin showed him how to use the caidgeal (bag net), one man wading down each side of the pool with a bhaiteal (staff) fixed to the net stretched between them to keep it down, with the bag of the net held back as well as possible against the current (ideally, a third person holds it). The net stretched wide, they advanced down the pool until they felt a tug. But the fish was too big to be caught in the meshes and kept going down on front of them. They shepherded it down to the shallow water where a decade earlier the junction had been, above the relict weir at the neck of Roger’s. There the fish got agitated and swam around trying to get in behind them, his back up out of the water. ‘Yer man thought it was a shark.’ They steered him back into the bag of the net and closed it around him. ‘He came in like a small child in on front of the net. There was power in him when we started to get him in to the bank. I’d say he done five houses. He was rough enough now, steaks on him that size.’ Hands are spread as though a football held. They could hardly manage the Muígnagúnla road on the Honda with ‘the shark’ and were nearly late for the match with all the excitement. Other interesting details from that tale are that there were no other fish in the pool – the fish had been on its own – and that it was pure silver. Dead fresh, in other words, just in from the sea, supporting Micky Martin’s contention that fish enter this river from the sea every month of the year.

The Molderings lasted just seventeen years in Lagduff. Everything about their set-up there had smacked of the very long haul. What turned them? The quiet? Hardly. That was the main attraction in the first place. Midges? Mike Anthony’s death in their kitchen surely shook them, but that was seven years before they left. More likely to have rattled them, I imagine, were their brushes with the law after the hatchet job on the river, the confiscated rifle and the death of her father. One can only speculate. Something might have happened on the stock exchange. It’s said they upped sticks and moved to the Azores, taking everything of value that they could. ‘Even he was leaving, he brought as much as he could, and he couldn’t bring the wheelbarrow. But he brought the wheel out of it.’

Or maybe they got an offer from the Office of Public Works? That outfit was in the throes of birthing Ballycroy National Park and didn’t hang about in snatching up the Moldering ranch. Headquarters, right at the edge of the park, what could be more idyllic? With the added bonus of a Kino downstairs when the world’s about to end. Whatever took them away, with the Molderings’ departure, the locality’s residential population reduced again to zero. Neither a house that none could pass nor a house that few could enter could sustain a living in this wild and lonely place.

The one that none could pass had lasted longer.